Writing Simpler Laws

Most political observers would agree that something has gone terribly wrong with how Congress conducts one of its core functions: drafting legislation.

Nowadays, bills are too long for our representatives to read, too complex for anyone to grasp, and too densely packed with alterations to the U.S. Code to discern which are significant. Major policy changes or spending proposals are typically buried deep within bills, never to be revealed unless some enterprising aide or whistleblower should discover them and raise a fuss. Even when these alterations are exposed, laws are often written in such opaque legal jargon that it's difficult to gauge whether such fuss is warranted. If dissenting lawmakers wish to challenge such provisions, there's no guarantee their concerns will be heard, as meaningful debate on whether the changes are justifiable as part of the many compromises and trade-offs contained in thousands of pages of legalese is nigh impossible. In short, legislation as we know it today is far too complicated and too technical — making it a boon to lawyers but a bane of democracy.

Complex statutes have not only undermined the functioning of the legislative branch, but the courts as well. Judges are often confronted with the need to "clean up" after lawmakers whenever a case involving long-winded, esoteric legal provisions raises questions of statutory interpretation. Discerning the precise boundaries of a term, phrase, or legislative stipulation whose meaning is disputed by the parties bringing suit depends on the assumption that its meaning exists and can be ascertained not only by skilled jurists, but by citizens and government officials who will need to comply with its dictates. The longer, wordier, and more technical a law is, the less judges should be confident they can make sense of it. In some cases, judges will refuse to enforce a provision because no citizen could reasonably be expected to know how to follow it. "In our constitutional order," wrote Justice Neil Gorsuch in the 2019 case United States v. Davis, "a vague law is no law at all."

Of course, an inherent feature of written laws is that they will at times contain ambiguities that judges must parse, and skillful interpretation of such language can set great judges apart in their craft. But that doesn't mean all laws are, or by nature must be, materially unclear. And while legal debates often focus on questions of statutory interpretation, less attention is paid to the ways Congress can make those questions less delicate by making its laws more clear. Put differently, perhaps we have been too focused on the "demand" side of statutory interpretation and not concerned enough about the "supply."

By rethinking the structure and style of legislation, Congress could address many of the problems that plague our governing institutions today — including overly complicated laws, a lack of democratic accountability, and the legislature's weakening role in our constitutional system relative to executive agencies and the courts.

WHY ARE LAWS SO COMPLEX?

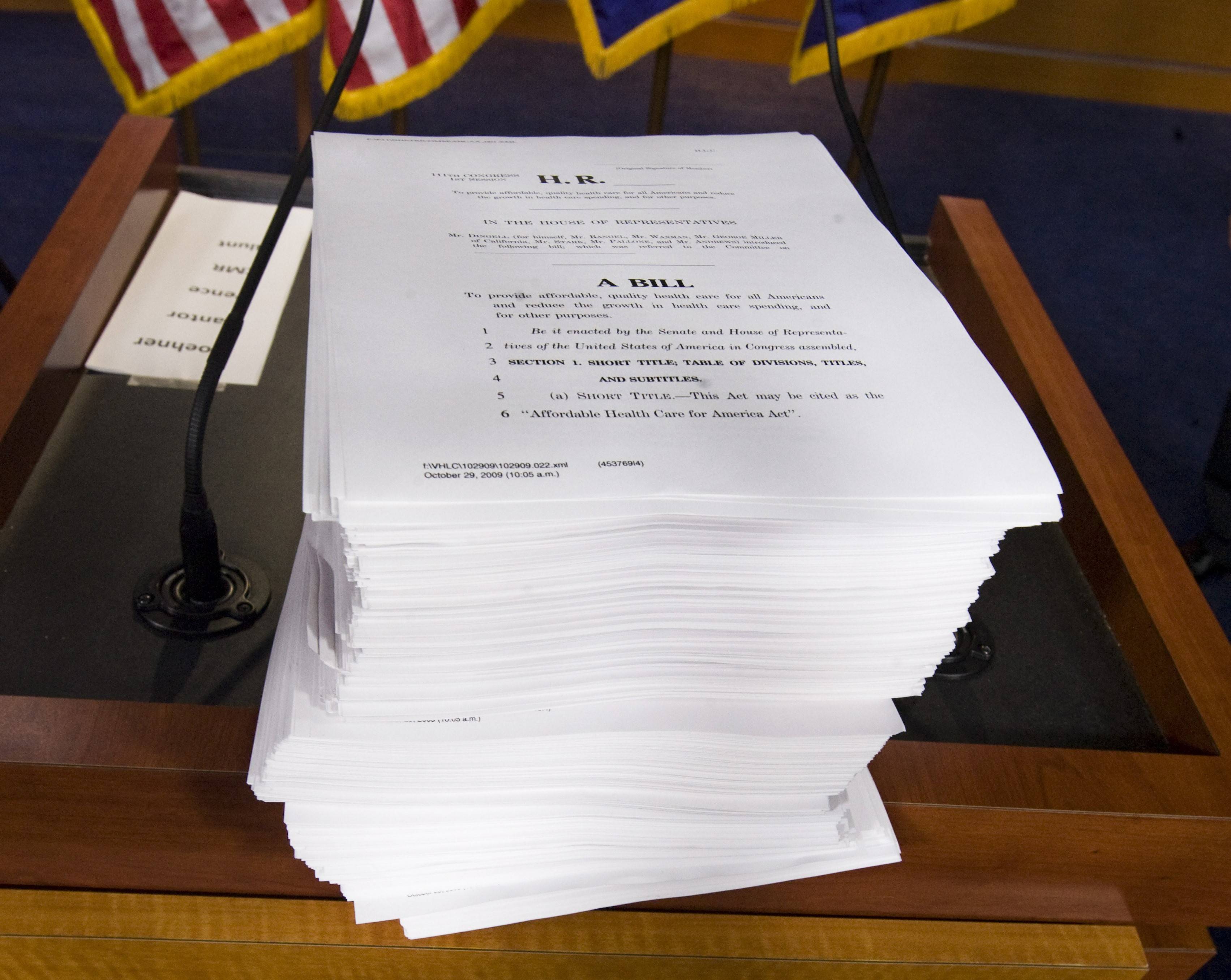

There are no objective measures that would allow us to assess changes in legislative complexity or ambiguity over time, but what we can measure is length. And in fact, legislation has grown longer in the decades since Lyndon Johnson's Great Society federalized many social programs. According to researchers at the Brookings Institution, the statutes passed by the 80th Congress in 1947-48 averaged just 2.5 pages long. That number had doubled by 1973, reached double digits by 1985, and rose to just under 18 pages in the decade between 2007 and 2017. Though these may not appear to be noteworthy changes, the fact that many statutes are simple authorizations that consist of only a page or two brings the average down substantially. Nowadays, it's not uncommon for a significant bill to run close to a thousand pages long.

As the length of statutes has increased, the number enacted into law has fallen. Polarization and congressional gridlock have incentivized lawmakers to stuff as many provisions as possible into each bill in the hopes that less popular ideas will be enacted as part of a more popular package. This is especially true of appropriations bills, which routinely run longer than a thousand pages and are increasingly the only significant pieces of legislation that Congress passes in a given year. Of course, the more provisions a bill includes, the lengthier and more complicated it becomes overall.

Other trends have contributed to the increasing length, complexity, and ambiguity of legislation. The proliferation of agency rules over the past half-century (during which the total number of pages in the Federal Register — a compilation of the rules promulgated by administrative agencies carrying out various statutory demands — tripled) suggests that there is a connection between congressional delegation of authority to the executive branch and legislative ambiguity and complexity. And it's not hard to see why: When Congress wants to delegate its lawmaking power to the administrative state, one of the best ways to do so is to write vague statutory provisions that leave significant room for agencies to maneuver. When it wants to reclaim power from the agencies, it reduces their discretion by drafting laws that are more specific and prescriptive.

Why would Congress wish to delegate its authority to another branch of government? From a practical standpoint, doing so can benefit individual members of Congress. By transferring rulemaking power to their preferred agency experts, representatives hoping to achieve policy goals without compromise can circumvent the legislative process. As Judge Neomi Rao has written, such legislation sacrifices the interest of "the collective Congress" in favor of members who can personally influence agency behavior after passing legislation. Though it is impossible to be perfectly precise when drafting a bill, the enormous growth in congressional delegation and administrative rulemaking suggests that legislation's increased ambiguity is at least in part a conscious choice.

Long, complicated, and vague laws benefit members in other ways as well. Length and complexity allow lawmakers to hide provisions that accommodate special interests. They also act as insulation, allowing members facing public scrutiny for their votes to say they could not have known the particulars of the entire bill. At the same time, ambiguity gives elected representatives a way to avoid electoral accountability. By outsourcing the details of lawmaking to agency bureaucrats, members can avoid criticism from constituents for doing the hard work of politics — making the trade-offs inherent to choosing a particular course of action — while appearing to do their jobs.

Thus, the most likely explanation for legislative length, complexity, and vagueness is at least in part a cynical one: Members benefit by writing long, complicated or otherwise imprecise legislation. This type of statutory construction undermines congressional accountability and, in turn, our entire constitutional system, perpetuating a cycle of congressional impotence, administrative predominance, and democratic atrophy.

A MATTER OF INTERPRETATION

As mentioned above, needlessly long and complex legislation not only impairs the functioning of Congress, but the courts as well. Highly technical or ambiguous laws are bound to confound judges no matter how advanced their interpretive skills. This is because proponents of the two major theories of statutory interpretation are locked in a debate regarding how to determine what the law is.

One prominent school of thought known as "textualism" holds that judges should look to the law as written — no more, no less — to determine what it means. To a textualist, a statute contains the only language legislators agreed to enact. Judges, therefore, should eschew extra-legal materials (save perhaps dictionaries and other technical interpretive guides) and limit their analysis to the text, with the goal of giving effect to statutory terms that everyone can look to when ascertaining how to fulfill their obligations or assert their rights in concert with the law.

The other major school, "purposivism," counters that statutes cannot encapsulate in writing everything their drafters intended to cover. And even if they could, the English language contains near-infinite ambiguities, meaning legislation will inevitably convey different things to different readers. Purposivists call on judges to breathe life into Congress's words by ascertaining the law's intent, accounting for lawmakers' goals, and determining how the legislative body would have wanted its words to be interpreted. They also advise that judges not shy away from scouring extra-legal materials for clues regarding the law's intended meaning or its most faithful application to the case at hand.

Textualism's best argument against purposivism was summed up by then-judge and now-Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh in a 2016 Harvard Law Review article. According to Kavanaugh, extra-legal materials like committee reports "are not necessarily reliable guides to the meaning of the text." "That is especially true," he continued, "when the statutory text represents a compromise among competing interests, as it so often does." And indeed, laws are passed by elected representatives voting on a particular set of propositions — those contained within the text. Members may have any number of idiosyncratic reasons for yea-ing or nay-ing the language ultimately put to a vote; the only accurate evidence we have of shared language and joint purpose among them is the written law as passed. Therefore, the only place judges can justifiably look to when interpreting a law is its text.

Purposivism's flaw, therefore (and it is a fatal flaw, if representative democracy is anything more than a sham) is that it attempts to sneak back into law that which was not voted upon and may only reflect the goals of some members who voted in its favor.

What's more, since laws are passed when elected representatives vote on a particular set of propositions — specifically, those contained within the text — relying on material not voted upon to interpret the law makes the meaning of laws impossible for the average citizen to discern. The vast majority of Americans don't have the time, resources, or expertise to sift through legislative history, committee reports, and related documents to determine what a particular provision might have meant to the representatives who voted for it. In order to follow the law, ordinary citizens need to know what the law is; expecting them to divine the congressional intent behind a provision the way a purposivist judge might is unreasonable.

But the textualist argument, which attempts to account for the realities of lawmaking, cannot withstand the challenges that contemporary legislation presents. To prevail against purposivism, textualists must insist that laws reflect some legitimate give-and-take between members of Congress. Yet there's no reason to believe that a bill, as written today, reflects such deliberation. Members simply cannot read legislation that runs longer than a thousand pages in the short amount of time they often have to do so, nor can they be expected to understand and debate it if they made an attempt. Legislation nowadays represents no more than the cobbled-together intentions of any lawmaker who managed to participate in the bill-writing process — a provision here from the representative from New York, a clause there from the representative from Idaho, etc. Once that process is complete, the bill is off to a vote without so much as a scan of the trade-offs contained in the document in its entirety.

Moreover, the canons of construction that textualist judges often rely on to interpret a law presume some structural integrity in the text as a whole. But as applied to modern legislation, this assumption is farcical. A bill cannot form a cohesive whole when it is constructed piecemeal by aides, attorneys, and congressional bureaucrats rather than drafted, reviewed, and critiqued by members. Even if legislators did hammer out the details of a given bill, many may not grasp its entirety — certain legislators may simply push to have a particular provision included, removed, or changed while ignoring the rest of the text. The upshot of all this is further ambiguity, since a single word cannot be guaranteed to have the same meaning in two places if one section was written by one member's staff and never reviewed, much less held up for clarification and debate, by any others.

In short, while the textualist critique of purposivism is compelling, the realities of modern legislation undercut the premises underlying textualism as an interpretive theory. Textualism is grounded in the understanding of legislation as traditionally conceived in our legal order. To shore up its foundational assumptions, we will need to bring today's legislation more in line with its earlier form.

SUMMARIZING STATUTES

Simplifying legislation would go a long way toward bolstering textualism, aiding judges in statutory interpretation, and bringing more democratic accountability to Congress's work. To see why, we must first consider what it is that representatives vote on today.

Contrary to textualist theory, the vast majority of lawmakers are not voting on the text. They are not superhuman, and neither are their staff. Members likely haven't read the text in its entirety, and even those who have cannot be expected to fully understand it.

But that doesn't mean representatives don't know what they're voting on. They, like every policy analyst seeking to understand what a bill is about, look to bill summaries and other secondary materials that attempt to explain, in layman's terms and at reasonable length, what a given bill contains.

Bill summaries can come from a variety of sources. Official versions are written by legislative counsel and committee staff. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) drafts the bill summaries that appear on Congress's website. Lobbyists and activists also write bill summaries, though theirs often contain slanted terms designed to undermine or gin up support for the legislation summarized.

Bill summaries are where textualism and purposivism collide. If textualists take seriously the idea that the text lawmakers vote upon should guide judges' interpretations of the law, judges should be interpreting the summaries that representatives use to decide their vote. And if purposivists wish to discern congressional intent, there's usually no clearer expression of what Congress is trying to accomplish (inasmuch as it is of one mind) than what appears in the summaries distributed by legislative counsel and committee staff — almost all of which include explicit statements of intent. To take just one example, the House Appropriations Committee's summary of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (the omnibus-spending and coronavirus-relief package that was enacted in December 2020) includes a clear statement of purpose regarding rural development and infrastructure: "The bill provides a total of almost $3.9 billion for rural development programs. These programs help create an environment for economic growth by providing business and housing opportunities and building sustainable rural infrastructure for the modern economy."

When applied to laws ratified in the form of bill summaries, the distinction between the two dominant theories of statutory interpretation would, in some respects, collapse. This is not just a happy coincidence: It reflects the reality that laws have become too unintelligible for judges to reliably grasp what they are interpreting. By leaving judges with too many options and too many opportunities to find and resolve ambiguities using their discretion, statutory complexity and ambiguity have contributed to a lack of judicial consistency. Those judges inclined to construe the text according to its plain meaning will be able to do so, and those inclined to deny the existence of plain meaning will have grounds to do so as well. Simpler laws — those that are shorter and written in terms of specific prescriptions and proscriptions under the banner of a clear goal — can resolve much of this confusion.

The solution to the problem of legislative complexity, then, is simple: Write future legislation in the form of a bill summary.

The utility of the bill-summary format becomes readily apparent when compared to its long-winded counterpart. Consider again the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021. This crucial piece of legislation — containing long-awaited pandemic relief for states, businesses, and individuals — spanned 5,593 pages when the House of Representatives voted to pass it on December 21, 2020. By contrast, the summary of the bill published by the House Appropriations Committee ran just 152 pages. That's hardly light reading — it's certainly enough to keep a member of Congress up late at night if pressed for time. But it is surely a plausible amount for even a non-lawyer to read and assess.

Of course, length is only part of the story. One provision of this massive bill involved the "extension of federal pandemic unemployment compensation" — a central part of the discussion surrounding federal aid for American citizens suffering during the Covid-19 pandemic. Here is a portion of that provision as it appears in the bill passed by the House:

SEC. 203. EXTENSION OF FEDERAL PANDEMIC UNEMPLOYMENT COMPENSATION. (a) IN GENERAL. — Section 2104(e) of the CARES Act (15 U.S.C. 9023(e)) is amended to read as follows: ‘‘(e) APPLICABILITY. — An agreement entered into under this section shall apply — ‘‘(1) to weeks of unemployment beginning after the date on which such agreement is entered into and ending on or before July 31, 2020; and ‘‘(2) to weeks of unemployment beginning after December 26, 2020 (or, if later, the date on which such agreement is entered into), and ending on or before March 14, 2021.''. (b) AMOUNT. — (1) IN GENERAL. — Section 2104(b) of the CARES Act (15 U.S.C. 9023(b)) is amended — (A) in paragraph (1)(B), by striking ‘‘of $600'' and inserting ‘‘equal to the amount specified in paragraph (3)''; and (B) by adding at the end the following new paragraph: ‘‘(3) AMOUNT OF FEDERAL PANDEMIC UNEMPLOYMENT COMPENSATION. — ‘‘(A) IN GENERAL. — The amount specified in this paragraph is the following amount: ‘‘(i) For weeks of unemployment beginning after the date on which an agreement is entered into under this section and ending on or before July 31, 2020, $600. ‘‘(ii) For weeks of unemployment beginning after December 26, 2020 (or, if later, the date on which such agreement is entered into), and ending on or before March 14, 2021, $300.''.

That's just a portion of one of the sections, and it's buried on page 1,934 of the bill.

The same provision is far more digestible in the summary compiled by committee staff:

Section 203. Extension of Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation. Restores the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) supplement to all state and federal unemployment benefits at $300 per week, starting after December 26 and ending March 14, 2021.

Which of the above is a representative more likely to use to color his perception of a bill on the House floor? And which better allows judges and citizens to determine what Congress, to the extent "congressional intent" exists, was aiming to do? The bill summary prevails on both counts.

Though it lacks the technical detail of today's legislation, the summary makes abundantly clear what Section 203 of the bill would do upon becoming law. And there's nothing stopping Congress from including a supplement to this law that offers the Office of Law Revision Counsel (OLRC) — the body responsible for integrating new legislation into the U.S. Code — more information on what it intends to amend. This way, the OLRC can continue to submit its independent, non-partisan effectuations of democratically enacted laws without forcing members and the public to dissect hundreds of pages of legalese to figure out what a given bill would do. Doing so would bring a clear, readable expression of the proposed legislation to the forefront while leaving the painstaking process of amending the U.S. Code to legal experts.

ANSWERING OBJECTIONS

There are several objections that critics might raise against writing and voting on legislation in the mold of bill summaries. Perhaps the most potent is that detailed, highly technical legislation is necessary to govern our increasingly complex society.

According to this argument, American society has become so complicated in modern times that states no longer have the expertise to oversee social and economic life without the federal government's direction or resources. To manage the situation, Congress created a web of federal programs to regulate commerce and pursue social goals through its power of the purse while delegating substantial rulemaking authority to expert administrators.

The primary vehicle through which this is accomplished is the appropriations bill — legislation whereby lawmakers allocate federal funds to specific federal departments, agencies, and programs. Appropriations bills have become not only the focal point of lawmaking, but one of the central sources of legislative complexity. They become particularly convoluted when enormous federal programs — including Medicaid, infrastructure spending, and education and training programs — are designed to award grants to states in ways that give them some discretion in their use of federal funds. States have at times been reckless and even dishonest with these funds, using them for purposes only tangentially related to the grant's purpose. It is no surprise, then, that Congress has sought to draft detailed, complex legislation that specifies precisely where certain funds must go.

Simplifying legislation might hinder this kind of congressional oversight, as Congress would have a hard time including detailed oversight mechanisms in so few words and without using technical jargon. Since limiting waste and abuse is otherwise a worthwhile policy goal, this would certainly constitute a trade-off that lawmakers should take into account when drafting simpler legislation. However, Congress is not without recourse on such matters of oversight.

For instance, lawmakers could rely on the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to put together secondary materials that would inform states' understanding of the bill at hand — similar to how the Congressional Budget Office provides Congress with fiscal analyses of proposed legislation. Lawmakers could also shift the bulk of state-oversight work to the executive branch. Given that oversight fits neatly within the executive's constitutional ken, this is a worthwhile option for lawmakers to consider.

Reshuffling some of the responsibilities of the congressional bureaucracy — particularly the Office of the Legislative Counsel (OLC), CRS, and the OLRC — could also significantly mitigate some of the trade-offs of writing shorter, simpler laws. At the OLC, non-partisan attorneys are charged with translating lawmakers' ideas into "clear, concise, and legally effective" language. But today's lawmaking incentive structures pit legal effectiveness against clarity and concision. One way to address the problem of complex laws, then, is to restore the balance between these values by emphasizing the latter two.

To do so, Congress could shift the power to draft bills to CRS (which, as noted above, already publishes bill summaries). A less dramatic fix would be for Congress to direct OLC attorneys to draft legislation that reflects the simplicity and style of a bill summary. The OLC should still produce the technical language that guides the OLRC in amending the U.S. Code, and the OLRC should maintain discretion as to how this is carried out. But these materials should be supplementary; the text lawmakers rely on during negotiations and votes, whether drafted by CRS or the OLC, should be written in summary form.

To ensure that the plain language of the law can be translated effectively to changes to the U.S. Code, the OLC and the OLRC should continue to collaborate. The GAO, meanwhile, should continue to keep a close eye on implementation and hold bad actors accountable. It should also provide lawmakers with feedback on any gaps left by shorter, simpler bills.

These aren't the only issues that might arise if lawmakers were to draft bills in the form of summaries: It's possible that the details that give the law its effect will be insufficiently fleshed out or omitted entirely, resulting in yet more delegation and administrative prerogative. Writing simpler legislation also runs the risk of removing from the spotlight the fine print that gives the law its appearance of legitimacy, which may be as important as the content of the particular statute. It could even be that making laws more readable will encourage the worst elements of democracy to emerge: Bodies designed to be somewhat detached from constituents — most notably the Senate — could become too responsive to voters. Simplifying bills would make them more accessible to the average citizen, and voters could use that knowledge to discourage their representatives from engaging in moderation and compromise. Responsible lawmakers shouldn't ignore these downsides; instead, they should remain cognizant of and work to mitigate them if they arise.

Changing the style of federal legislation will not come easily, or without trade-offs. But on net, shorter, simpler laws would go a long way toward enhancing the efficacy and accountability of our federal legislative branch.

A CONSTITUTIONAL CONGRESS

"[O]ur current methods of making law," wrote legal scholar David Schoenbrod, "are neither as natural nor as inevitable as our habitual use of them makes them seem." While he was referring to Congress's propensity to delegate power to the executive branch, his observation is equally suited to the quasi-delegation that occurs when Congress drafts complex laws that will inevitably require agencies' and courts' interpretations.

Writing laws in such a manner is not a hallowed tradition, nor is it an inevitability. It is, to use Schoenbrod's terms, "a product of its time." This practice "reduces government's capacity...to effect compromises and therefore resolve disputes about what the law should be." It ought to be rolled back.

Simpler laws are not a panacea for the problems inherent to the modern Congress, which include lawmakers using their seats to audition for cable news, "compromise" being regarded as a dirty word, members spending most of their time fundraising and campaigning for reelection, omnibus appropriations becoming the default mode of lawmaking, and elected representatives continuing to evade accountability by intentionally writing vague statutory provisions that delegate decision-making to agencies. But they would be a step in the right direction.

Writing bills in summary form would make Congress both more democratic and more constitutional. It would increase lawmaker accountability by making laws more accessible to the public. It would foster a culture in which members are expected to read the bills they vote upon. It would eliminate the need for lawmakers to rely on biased bill summaries from activist groups and lobbyists when deciding how to vote. And it would result in a Congress that better fulfills its constitutional duties of facilitating debate, compromise, and self-government.

Such a reform could also relieve pressure on the judiciary, which has supplanted Congress as the place where Americans resolve their most pressing debates. Laws written in plain language could never remove all ambiguity from legislation, but they could minimize how often courts are asked to resolve hot-button political disputes couched as questions of statutory interpretation — a task better left to Congress. After all, the text is much harder to ignore or reason around when it means something obvious to both judges and citizens.

Americans have a hard enough time trying to figure out what the law should be. They should welcome a reform that would make it a little easier to figure out what the law is.