The Miseducation of America's Teachers

If medical professionals spoke about early career doctors the way school administrators talk about early career teachers, no one would enter a hospital again. "Oh, everyone kills a few patients early on," a caring mentor assures an internist who prescribed the wrong medication. "The only way to learn is to dive in and poke around," says a veteran surgeon to a young resident about to perform his first tracheotomy.

Unfortunately, these are common sentiments among educators in America. No novice teacher is armed with the knowledge or skills to run a classroom; it's simply assumed that they'll fail early on. In fact, making it through the blistering first year — the classroom chaos, the unforgiving workloads, the confusing curricula, the daily student insolence — is something of a rite of passage. Veterans clap rookies on the back and assure them they'll make it through, knowing that the first few years will be rough — for both the teacher and his students.

The reason for this reality is simple: Our nation's teacher-preparation system is broken. Our educators enter the profession woefully unprepared for their jobs. The large majority attend programs at university schools of education, where they read and discuss esoteric academic literature that contains no references to classroom-management techniques, lesson pacing, learning assessments, or other practical knowledge. These schools are boxing academies that don't teach their students how to duck and weave.

I experienced the consequences during my first year of teaching. Lectures on tort law and transgender literacies didn't equip me to handle a student who slugged another in the face during class. Nor did a few mock lessons equip me to fill 50 minutes of class time for several different classes five days a week.

I'm not alone in my criticisms. Arthur Levine, the former president of Columbia Teachers College (arguably the most prestigious teacher-preparation institution in the country), observed that "the education our teachers receive today is determined more by ideology and personal predilection than the needs of our children." It was as if the president of Ford Motor Company had said that America makes lackluster cars.

Levine's two-decades-old report eviscerated the state of teacher preparation in America, and little has changed since. In 2010, half of all U.S. education professors believed that "teacher education programs often fail to prepare teachers for the challenges of teaching." Sixty-two percent of program alumni agreed. Three years later, the National Council on Teacher Quality characterized teacher preparation in this country as "an industry of mediocrity."

But the problem is far worse than mediocrity. Over the past few years, stories have surfaced about history-class materials celebrating communism, math lessons that focus on how we can use mathematics to advance activism, professional-development materials that teach educators about critical-race and whiteness theories, and a seemingly endless supply of similarly politically charged content for the K-12 classroom. Our schools have been mediocre for decades; now they're politicized, too.

Fixing our broken pipeline of teachers is imperative. The quality of a teacher is the single most important school-related factor in a child's education — more important than district policy, leadership, or facilities. Effective teachers are associated with quality-of-life indicators as disparate as lower rates of teenage pregnancy and higher savings for retirement. The difference between the best and worst teachers determines months' worth of learning gains or losses for millions of students every year. Reforming our teacher-preparation institutions could thus be one of the most important levers for improving the state of American education.

INPUTS AND OUTPUTS

Before the modern education-reform movement — which began in 1983 with the National Commission on Excellence in Education's bombshell report, A Nation at Risk — most researchers and advocates evaluated schools and their surrounding institutions through inputs: How extensive are their resources? What materials are they using? Who are the people in charge?

A Nation at Risk — which warned that America had for decades been "committing an act of unthinking, unilateral educational disarmament" — shifted the focus to outputs. With the onset of mass standardized testing under the George W. Bush and Obama administrations, researchers soon acquired the data needed to compare the outputs of various policies and interventions.

Studies based on these data have since found that formal teacher credentialing has little effect on teacher performance. One study from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) looked into newly hired teachers in New York City. Its conclusion was simple: Credentialing and formal training slightly improved a teacher's effectiveness for the first few years of his career, but overall, there was "little difference in the average academic achievement impacts" of certified versus non-certified teachers. In other words, graduating from a formal training program helps a teacher initially, which makes sense: Formally trained teachers, who gain experience as student teachers, begin a lap ahead of teachers without such training. But other factors quickly overtake credentialing in importance.

Researchers also compared alternatively certified educators — such as those who enter the profession through Teach for America (TFA) — to traditionally trained ones. They found that alternatively certified teachers outperformed their traditionally trained counterparts when they began teaching.

Another NBER study examined data sets in North Carolina and drew similar conclusions: Credentialing matters for early-career educators, but factors like teachers' test scores and their undergraduate institution's prestige matter just as much, if not more. If anything, the data suggest that formal credentialing screens for other characteristics associated with teacher effectiveness, such as work ethic and natural intelligence; it does not appear to improve teacher performance. In fact, the researchers also found that advanced graduate degrees in education can have a negative effect on a teacher's performance in the classroom.

Harvard economist Roland Fryer unearthed even bleaker data while researching charter schools in New York City: "[S]chools with more certified teachers have annual math gains that are 0.043 standard deviations lower than other schools. Schools with more teachers with a master's degree have annual English language arts (ELA) gains that are 0.034 standard deviations lower." In other words, higher numbers of credentialed staff correlated with lower academic gains for students.

Defenders of teacher-preparation programs are quick to suggest that variable quality in programs might be the issue here. Some institutions surely spend too much time on theory, they may admit, but we shouldn't lump the ineffective few in with the largely effective majority. Recent evidence, however, indicates that there is little variation in program quality among teacher-preparation institutions: Standout programs are the exception that prove the rule.

Other defenders point out that alternative licensing avenues tend to produce teachers with high turnover rates. While it's true that TFA-teacher turnover is higher than that of more traditionally trained teachers, a recent analysis found that the boost TFA teachers provide to student performance is significant enough to make the program a net positive for students in both the short and the long run.

In sum, formal training can offer an early career boost to a teacher, but any difference between certified and non-certified teachers disappears within the first few years. Moreover, alternative training programs — which tend to be less expensive and less time intensive than traditional ones — are just as, if not more, effective than others.

WHAT TEACHERS ARE TAUGHT

A cursory glance at what occurs inside these programs helps explain their profound failure to equip teachers with the knowledge and skills they need to educate America's youth.

Researchers have conducted several reviews of teacher-preparation programs' curricula. The most recent comes from the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty (WILL), which reviewed the required coursework for 13 programs for teachers-to-be in the Badger State. The syllabi were replete with courses like "Foundations of Diversity and Equity in Education" and "Equity Education & Culturally Relevant Pedagogy in the Multicultural Classroom." Prospective teachers were required to read books like Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Education Policy for Social Change, White Fragility, and An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education. They discussed articles like, "Decolonizing the Classroom," "Moving Beyond Tolerance in Education," and "Creating Classrooms for Equity and Justice." Even the more innocuously titled courses, like "History of American Education" and "Education Policy Studies," contained these sorts of materials. The programs defined education not as anything resembling formal academic training or character formation, but as a "social justice and change agent."

Other reviews substantiate the portrait WILL paints. The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal solicited syllabi from three of the country's most prestigious schools of education to tally the most commonly assigned readings. Lo and behold, the syllabi were awash in progressive pieties and even outright Marxism.

Notably, the work of Gloria Ladson-Billings — whose most famous intellectual contribution was introducing critical theory to the field of education — topped the list. She argues that teachers will have to "expose racism in education and propose radical solutions for addressing it." Where she discusses actual learning, it's only to castigate traditional curricula as "culturally specific artifact[s] designed to maintain a white supremacist master script."

Another frequent flier on lists of assigned readings is Paulo Freire, a Brazilian Marxist who cites Maoist and Russian revolutionaries approvingly in his work. It's hard to encapsulate the saint-like status Freire has in such institutions. Like Ladson-Billings, his vision is patently radical: He believes the role of the educator is not to teach, but to raise students' critical consciousness — a discontent he hopes will lead to revolution.

Reviewing the lists, almost all readings fall under two philosophies of education. The first, critical pedagogy, has roots in Freire's thought. It envisions classrooms not as traditional academic centers, but as the loci of radical societal change.

The second philosophy, progressive education, reaches back to educational reformer John Dewey, who wrote that there is no content "that is in and of itself...such that inherent educational value can be attributed to it." He argued that, rather than imparting knowledge to students, educators should leave students to explore and discover the world for themselves. He emphasized student direction over teacher guidance, skills over knowledge, student interest over literary merit. Where teachers do provide direction, he insisted it must be in the form of projects that resemble authentic, real-world work — learning math by designing bridges, literature by performing it, or science by doing lab work.

When Dewey first proposed these ideas in the early 20th century, social science was in its infancy. His theories seemed plausible: Students learn spoken language and motor movements through experimentation and play — why not the rest of human knowledge, too? There were no randomized-controlled trials or meta-analyses at the time to either substantiate or disprove his claims. Of course, the education sciences have evolved since then, and several decades worth of research has discredited such student-directed approaches.

Education professor David Steiner, who ran his own curricular review of teacher-preparation schools, makes particular note of what these programs lack: materials written by conservatives or traditionalists, essays older than 30 years, and courses on the history or philosophy of education. Few if any programs require teachers to show mastery of basic teaching skills. He characterizes these programs as "intellectually barren" and efforts to "shape the fundamental worldview of future teachers," not train effective ones.

Consider one element of essential pedagogic knowledge: the science of reading. Only 28% of American teacher-preparation programs sufficiently address all components of reading instruction (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension). Twenty-two percent do not adequately cover any of them. The dark irony here is that the kind of practical training that would help bring about real, constructive social change — such as raising the literacy rates of underserved communities — is shouldered out of these programs by readings on social-justice education.

These two ideologies — one politically noxious, the other academically inferior — have made their way into our education system in part through public policy. Accreditation standards, which come from a confusing mixture of state-level policies and directives from national accrediting bodies, outline the criteria these programs must adhere to if they are to obtain and keep their accreditation status.

At the state level, consider Illinois's Culturally Responsive Teaching and Leading Standards, signed into law in 2021. These standards, which are to be implemented in teacher-preparation programs in the state, require that teachers "support and create opportunities for student advocacy." They identify "raising consciousness" as an element of instruction. Teachers are encouraged to include a "broader modality of student assessments" that include "social justice work" and "action research projects," wherein students investigate and advocate for various political causes.

As for the national level, the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP) is the largest accrediting body for teacher-preparation programs in the country. CAEP standards make mention of safe learning environments, reflection on personal biases, and diversity, equity, and inclusion, but contain nary a reference to anything foundational to instruction, such as the cognitive science of learning. Where it focuses on preparation standards, the statements it provides — candidates are able to "apply critical concepts and principles of learner development" and "apply their knowledge of the learner and learning at the appropriate progression level" — are vague to the point of uselessness.

At best, these institutions advance a politically neutral, albeit largely ineffective, approach to the classroom. At worst, they're radical institutions instilling our country's teaching force with a neo-Marxist worldview. In neither case do they advance a clear vision for an education that might stir the mind, form the character, or enliven the soul, nor do they provide the practical training necessary to advance such an education.

AN INHERITANCE LOST

Of course, this state of affairs didn't pop into existence ex nihilo: There's a history that brought us to this point.

Once upon a time, education was a privilege of the affluent. Aristocratic families were the only ones who could afford to hire tutors to educate their own children. Beginning with the Jesuits, the Catholic Church attempted to systematize mass education, but access to schooling remained an entitlement for the few. Then during the 19th century, when the common-school movement led by Horace Mann democratized education, there was a sudden need for a vast teaching workforce.

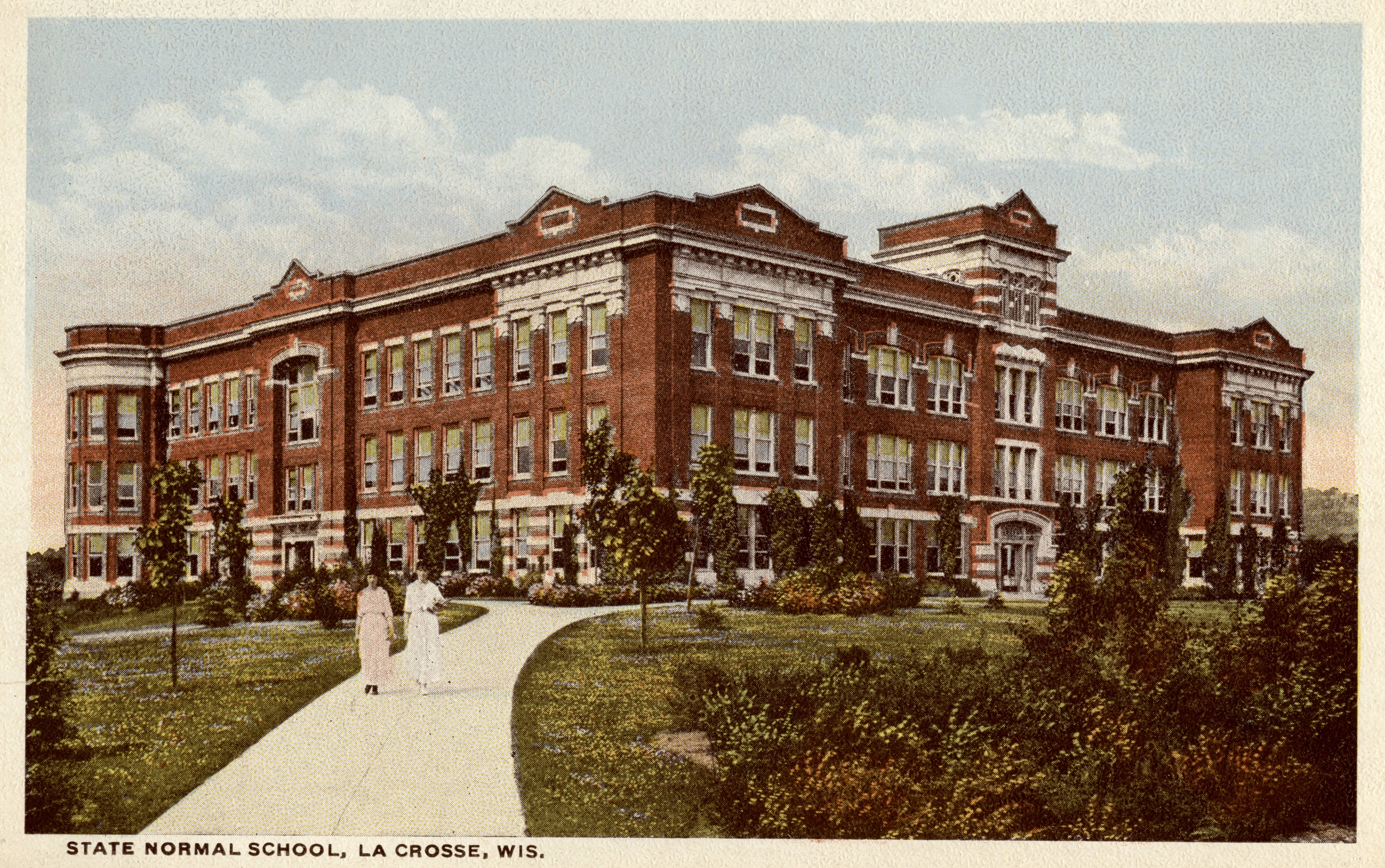

For the first several decades, normal schools developed to train teachers for America's expanding universal public-education system. According to Arthur Levine, these institutions taught an "eclectic mix of basic subject matter and pedagogy." They amounted to little more than an additional year of schooling to make sure prospective teachers understood basic math and had some rudimentary understanding of classroom management.

However, as accreditation and professional associations began to form and high schools sprouted up across the country, normal schools enhanced their admissions standards and extended their training. They began to associate with universities and launch fledgling research activities. By the 1940s, almost every normal school had either closed or been subsumed into a university department.

Unfortunately, associating with universities fostered the pressures and envies of prestige and intellectual prowess. Looking to find credibility alongside more traditional departments like English and philosophy, teaching programs attenuated their connections with K-12 schools and dropped their emphasis on practical skills to focus on theory.

This transition from normal schools to university education departments coincided with the broader progressive movement. Before the 20th century, American education was classical in nature — the curriculum consisted of grammar, rhetoric, and great books; learning primarily involved memorization and direct teacher guidance. Dewey, along with progressive education philosopher William Kilpatrick, replaced this popular approach with their own dubious ideas, training some 35,000 students in their methods and writing essays that influenced many more. That their theories were associated with universities stamped them with the mark of scholarly merit. Over time, progressivism supplanted classicalism in American schools.

Unfortunately, when Dewey left the scene, he also left behind a vacuum. Before his work reshaped American schooling, education was seen largely as transmission — the passing down of an intellectual inheritance. Dewey rejected such reverence for a traditional body of knowledge. For him and other progressive educators, the choice of content is inconsequential: Let students read anything, be it Plutarch or a tweet, so long as they're reading. Deconstructionists like Freire were happy to provide the content that would fill the void. As a result, the traditions of the West were now seen as worse than neutral; they were racist, sexist, and oppressive. Children were not only to be liberated of social impositions, but to actively shape society to suit their own desires.

Stripping education of tradition and knowledge leaves schools with no telos. Without a clear purpose, they drift toward either political advocacy or the kind of solipsistic navel-gazing we see in teachings on identity. Teachers, meanwhile, go from custodians of our shared cultural knowledge to co-advocates in a radical social project.

This blend of ideological corruption and pedagogical mediocrity spread through America's educational institutions for decades, spilling flawed theories, practices, and curricula into K-12 schools until these became the assumed wisdom. Cleaning up this ideological capture will take decades as well. But there are several policies that lawmakers and university administrators can implement now to begin this process.

WHAT'S TO BE DONE

In all honesty, the opening comparison of teachers to doctors is unfair. A quick analysis of the distinctions between the two will direct us toward a better way to train our teachers.

For starters, being a successful doctor requires a broad understanding of the parts and processes that allow the human body to function. Medical schools thus provide their students with a glut of information about chemistry, biology, anatomy, neurology, and more. By contrast, there is less profession-specific knowledge and expertise required to run a classroom. Teaching is more akin to journalism or running a business: There are practices and formal procedures worth learning, of course, but such knowledge is not necessarily linked to success.

Experience also matters for each of these professions. Medical-school students may memorize the names of all the bones, muscles, and organs that make up the human anatomy, but the residency training that follows gives them a chance to learn from practicing doctors and put their knowledge to use. Likewise, a foreign-affairs correspondent should know something about the country he is covering, but he learns the trade of journalism from experienced staff and on-the-ground work. Even business owners must know something about the product they're selling. But certain knowledge only comes with experience.

The consequences of failure in each profession also differ, meaning we place different guardrails around them. If a business fails, a town may lose an employer or a beloved institution, but the business owner himself bears most of the responsibility as well as the cost. Conversely, if a doctor fails, he risks other people's lives. Because of these differences, we require doctors to meet rigorous licensing standards, while the barriers to entry for business owners are all but non-existent. Education lies between the two: A third party is harmed when teachers fail in their duties, but the consequences are not as clear cut or irreversible as life and death. Responsibility is also far more dispersed: If Johnny can't read by third grade, whose fault is it?

This doesn't mean we shouldn't install any guardrails around the teaching profession. An actuary may, with some coaching, become an exceptional math teacher, but we don't want to allow just anyone access to children with zero vetting.

To effectively carry out their mission, teacher-preparation programs and licensing laws must emphasize content knowledge and experience while maintaining some basic standards of competency for entry. As discussed above, there are few if any formal programs that train teachers well. TFA is notable for its success, but it admits students based on standards that rival those of Ivy League colleges. This screening leaves many wondering what causes its success: Does TFA succeed because it trains teachers effectively, or because it enlists the smartest, most driven applicants?

Perhaps a better model might be that of many successful charter schools. Institutions like Success Academy do not require formal licensure for hiring; instead, they seek young aspiring teachers with time on their hands and a degree in what they'd teach. Schools more generally might find greater success if they followed a similar model: trusting the university to provide teachers with the necessary content knowledge but assuming the responsibility for training themselves.

We have some examples of successful efforts to nudge schools of education in the right direction. Most notable among these are the National Council on Teacher Quality's (NCTQ) rankings of teacher-preparation schools. After NCTQ's first rankings were released in 2013, many teacher-preparation institutions offered their students more guidance in evidence-backed literacy instruction and classroom-management techniques. Unfortunately, these improvements remained peripheral. Pressure from an advocacy organization can only accomplish so much; policy changes must bolster these efforts.

What follows are three policy reforms that would push teacher preparation in the correct direction, away from formal licensing and toward a system that prioritizes relevant knowledge and experiential training.

The first step would be to modify accreditation standards. Researchers have amassed a vast body of evidence on what works in the classroom, and like journalistic writing or suturing procedures, these practices are trainable. We know that the most effective teachers run structured classrooms, have a warm but strict classroom presence, and spend lots of time actively instructing students rather than simply monitoring activities. We know that methods like spaced and structured practice, worked examples, direct instruction, guided discussions, and regular low-stakes quizzing have clear educational value. Finally, thanks to advances in cognitive science, we have concepts and techniques to draw from — such as working memory, automaticity, and chunking — that prospective teachers can study and apply to ensure that their students are learning.

Accrediting standards should ensure that institutions are training future teachers in these effective practices and liberal theories of education. In place of vague allusions to "critical concepts," they should require aspiring teachers to learn about what cognitive science has taught us about how children learn. In place of faddish shibboleths like "equity" and "diversity," they should require programs to train teachers in the tried and true methods of classroom management and instruction. For courses on education theory, accreditors should encourage programs to incorporate voices in their reading lists that represent diverse perspectives on the subject. Replacing even one or two radicals on the typical syllabus with educational traditionalists like E. D. Hirsch or Doug Lemov would inject a healthy dose of sanity into ailing institutions.

The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) — a project of the U.S. Department of Education's Institute of Education Science — could serve as a promising source of alternative accrediting standards. WWC publishes practice guides that summarize research and distill it into practical instructional techniques. As my state of Wisconsin outsources its accrediting standards to progressive groups like the National Council of Teachers of English — which recently declared that "the time has come to decenter book reading and essay writing as the pinnacles of English language arts education" — a state-level policymaker could compel schools of education to align their preparation programs to the best practices outlined by the WWC.

Policymakers should also open pathways for alternatively licensed teachers. As noted above, there is little difference in effectiveness between traditionally and alternatively licensed teachers. Yet the series of hoops that prospective teachers must jump through to acquire a license discourages many highly qualified candidates from entering the profession. In my own city, a former attorney and business litigator who runs a respected program at a private school wonders why he's precluded from teaching Milwaukee public-school students about the Constitution. There are many other late-career lawyers — as well as journalists, accountants, graphic designers, mechanics, business owners, and more — who have a wealth of experience and knowledge to offer students, but onerous licensing requirements keep them from doing so.

Many states have gone a long way toward loosening licensing laws and fostering alternative training programs. Although they'll face plenty of criticism from teachers' unions (whose members benefit from burdensome licensing rules), policymakers can continue in this direction knowing that students will benefit in the long run. If antiquated licensing rules must persist, they should emphasize degrees in English, science, math, or history rather than education. Our current system mistakenly prioritizes degrees in education theory over content knowledge; licensure reform could reverse that emphasis.

If content knowledge constitutes half of what makes for an effective teacher, experience constitutes the other half. Apprenticeship models, wherein prospective teachers earn a bachelor's degree by working in the classroom, could vastly improve the current system. Tennessee pioneered the first such program just last year, requiring prospective teachers to participate in paid on-the-job training in classrooms — much like a short medical-residency program. Since then, Ohio and South Dakota have created and expanded similar pathways.

I used to work in an urban school with many unlicensed albeit well-qualified teachers' aides. They were far more knowledgeable and effective than the rookies fresh out of teacher-preparation programs, but most had no intention of completing formal training because of either the cost or the time requirements. Oftentimes rookie teachers at the school would quit within a few months, and the unlicensed aides would fill in for a while. But they could not remain the teacher of record without the proper licensure. Offering these individuals a path to a license with lower costs and fewer hurdles would give them a much-deserved pay bump, a prestige boost, and incentive to remain in the profession.

A LOW BAR

I think back to my first years teaching and wince at what my students experienced. They likely learned next to nothing, while students taught by my veteran counterpart learned an academic year's worth of math, science, history, and English.

Our current teacher-preparation system does an obvious disservice to students. But it also disserves our teachers. The turnover rates in the first years of teaching are worryingly high; too many young teachers, unprepared for what they are about to encounter in the classroom, quit early in their careers because of the constant stress and looming sense of failure.

As school-choice legislation spreads across the country, remaking the very structure of American education, it's all the more imperative that the institutions educating our teachers are doing their job well. The current state of teachers' colleges makes one wonder how beneficial school-choice legislation will be. To rephrase an old quote by Henry Ford, you can choose any teacher you want, so long as he's mediocre and a leftist.

Perhaps it's cynical to consider our nation's schooling this way. But reforming the way we prepare teachers in America is a hopeful endeavor precisely because the quality is already so low. Even middling improvements in the teacher pipeline could substantially improve the system as a whole not only for teachers, but for the students they teach and the communities they serve.