Industrial Policy in the Real World

Historians and commentators will wrestle with Donald Trump's legacy for some time, but one of his most significant accomplishments was the shake-up of the Republican Party's economic platform. His appeal among working-class voters, especially in the Midwest, invigorated a wing of the party that has grown increasingly concerned with the country's economic future. These national conservatives are clamoring for an industrial policy that would promote American manufacturing and reshoring, which it views as the surest way to revive the American economy and solidify the GOP as the party of the working class.

For others on the right, Trump unleashed a skepticism of the free-trade consensus that has dominated politics for the last three decades. Though they are less determined to pursue a holistic industrial policy than are manufacturing advocates, these conservatives nonetheless support shoring up domestic industries seen as vital to national security. Their case has become all the more urgent in recent years thanks to the rise of China and the Covid-19 pandemic, the latter of which exposed America's dependence on foreign manufacturers for emergency supplies. In short, for both emerging factions on the right, industrial policy is an idea whose time has come.

In their estimation, the Republican Party's pro-business agenda is responsible for particularly bad policy, and the American people have suffered for it. Nathan Hitchen offers a distilled version of the industrialists' critique in an October 2020 essay for the American Conservative. "American society," he writes, "has settled for a contract exchanging production for consumption, long-term prospects for near-term profits, and commonwealth for private wealth." He favors replacing this "economist view" with what he calls the "statesman view," the essence of which "is that there is a statesman at the helm of government building up the body politic for the good of the whole people."

Not every advocate of industrial policy would go so far as to argue for one individual to make all the decisions — particularly if they have substantial disagreements with whomever happens to occupy the Oval Office. Nonetheless, most do place their faith in a few far-sighted public servants making decisions and implementing policy according to the national interest.

Just as the Tea Party rarely tired of quoting James Madison and Thomas Jefferson on the perils of big government and the virtues of checks and balances, the emerging industrial-policy factions on the right ground their arguments in the American founding. They insist that the framers wanted the country to have an active, centralized industrial policy, that the establishments in Washington and New York have thrown away this legacy for a mess of pottage, and that enlightened statesmen and technocratic experts can revive this tradition — and the American economy along with it.

Though some aspects of their criticism are well founded, the history of American economic policy provides as much a warning for industrial-policy advocates as it does a guide. A closer look at the past reveals the intractable challenges these would-be planners face, thanks in large part to the governing framework the framers established.

RETHINKING THE INDUSTRIALIST NARRATIVE

Early American history, as seen through the eyes of industrial-policy advocates, began soon after George Washington entered office, when Alexander Hamilton — his treasury secretary and fellow Federalist — proposed a visionary set of policies to transition the United States from an agrarian society to an international finance and manufacturing center. The most dynamic sectors of the American economy supported Hamilton, but Jefferson and members of his Democratic-Republican Party preferred to preserve America's agrarian elements. Although the Washington and Adams administrations adopted parts of Hamilton's program, the Jeffersonians undid most of his work as soon as they took over.

The War of 1812 exposed the folly of Jefferson's strategy. Even before the war began, the embargo he placed on exports to England devastated the American economy, while Congress's decision to let the charter of Hamilton's First Bank of the United States expire was similarly counterproductive. Chastened by the burning of the Capitol, the desultory stalemate along the Canadian border, and the new nation's general inability to fight Britain, the Jeffersonians realized the error of their ways, chartered a Second Bank of the United States, and adopted a protective tariff to support manufacturers. Later on, Henry Clay proposed an "American System" to modernize the economy through protective tariffs, infrastructure improvement, and centralized banking. The 1828 tariff represented the high-water mark of this effort.

Yet soon afterward, Andrew Jackson's electoral victory ushered in the party system that dominated antebellum politics and stymied industrial policy for decades. He vetoed infrastructure bills, refused to renew the Second Bank of the United States, and kept the federal government too weak to threaten slavery in the South. Only with the onset of the Civil War was the Republican Party able to push for enlightened industrial policies — like supporting the transcontinental railroad and raising tariffs — that paved the way for the United States to become the pre-eminent economic superpower of the 20th century.

Though there is some truth to this story, the verdict in favor of industrial policy is not quite so clear. A less hidebound narrative would acknowledge the fact that, from the beginning, the United States has enacted confused and often incoherent industrial policies driven primarily by political, rather than strategic, considerations. Nevertheless, the American economy powered through.

From the beginning, the nation's leaders were indeed of two minds on the best way forward for the country's economy. Hamilton preferred to emulate Great Britain's economic success by pushing to strengthen the American financial sector and boost the manufacturing economy. To do so, he thought the federal government should assume the states' debts and foster the domestic credit market by paying off their loans. To that end, his famous Report on the Subject of Manufactures — much of which was written by his deputy, Tench Coxe — called for modest increases to certain tariffs and federal subsidies for important industries.

Jefferson, on the other hand, was skeptical of the manufacturing industry. As a Southerner and an avid reader of classical political theory, he argued that independent farmers who owned their own land and commanded their own destinies would provide the strongest bulwark against tyranny. He also wanted to end the restrictions that Britain had imposed on the colonies and break England's influence on the American economy, even at the cost of a trade war. Instead of tariffs just high enough to support the nation's finances, Jefferson favored reciprocal tariffs and other tit-for-tat measures designed to either reduce American dependence on British imports or force Britain to lower its tariffs.

In 1792, Congress adopted Hamilton's modest tariff increases, but not his proposed subsidies. Shortly afterward, something odd occurred. American manufacturers, who had largely allied themselves with the pro-industrial Federalists, began warming up to the Jeffersonian approach. This was particularly the case for owners of smaller manufacturing firms, who realized Hamilton's proposed subsidies would inevitably flow to their larger, politically connected competitors. New York's General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen defected from the Federalist Party in 1794 to side with Jefferson. Coxe himself followed close behind. By 1809, Democratic-Republicans were citing the Report on Manufactures on the House floor, while Jefferson's trade-disrupting embargo favored America's new factories.

Hamilton held fast to his program even as his party bled followers. But after his death in 1804, the Federalists realized that in order to maintain what little support they had left, they had to make a decision: They could either continue to support Hamilton's vision of moderate tariffs and the subsidies necessary to stabilize the financial sector, which was losing ground politically, or they could push for raising tariffs high enough to protect American manufacturing, which was now more appealing to the financial and mercantile industries in their New England stronghold. In the end, they chose the former.

The Federalist and Democratic-Republican platforms thus shifted — but not because party leaders had changed their minds about what was best for the country. They did so primarily due to the parochial interests of coalition members and internal party dynamics.

Similar forces were at work behind the 1816 tariff. In 1810, New England businessman Francis Cabot Lowell famously circumvented British export controls by visiting cotton mills in Lancashire, England, and discerning how their power looms worked. Upon returning home, he built his own looms in Massachusetts. Rather than reproducing the sort of fine, higher-end textiles made in England, Lowell's mill produced coarse, low-quality textiles more similar to those produced in India. Yet even with this new technology, Lowell could not compete with Indian producers. His solution was to lobby Congress for a tariff.

Securing the passage of this proposal was no easy feat. Lowell knew that the largest market for the raw cotton produced in the American South was in England, meaning Southern plantation owners would staunchly oppose any tariffs that might reduce demand for English cotton textiles or drive London to retaliate against their wares. His solution was to push for a tariff that would harshly penalize the coarser textiles produced in India but leave a relatively light rate on the finer textiles produced in England. This combination was amenable to both Massachusetts factory owners and South Carolinian plantation owners, and it sailed through Congress in 1816.

Some supporters of the 1816 tariff may have viewed it as a way to build up America's manufacturing industry and reduce English influence in the American economy. But by the time the bill made it through Congress, it not only pushed American manufacturing down the value chain, it also entrenched English imports. What's more, it left Rhode Island's more advanced textile manufacturers — whose products competed with those produced in England — with little protection, and few of them survived the subsequent decade. Lowell's firm prospered, however, as did the plantation owners who exported their cotton to the United Kingdom.

The 1828 tariff was even more distortionary than its 1816 predecessor. At the time, President John Quincy Adams and his secretary of state, Henry Clay, supported Clay's American System — a comprehensive, nationalist plan that involved high tariffs on manufactured imports and federal spending on infrastructure projects to bind the country together. Clay insisted that by making the American economy more balanced, more integrated, and more self-sufficient, his plan would benefit the country as a whole.

The South, which supported Andrew Jackson, generally opposed Clay's plan, but the tariff proposal gained the favor of manufacturers in Adams's stronghold of New England. The spending element was popular in the swing states of the Midwest and the Mid-Atlantic, where the need for infrastructure was as great as the ability to fund such projects was lacking. Yet the Midwestern and Mid-Atlantic states would only agree to higher tariffs on manufactured imports if Congress also raised duties on raw-material imports that competed with those produced in the middle regions of the country — a proposal that New England manufacturers, who relied on low raw-material prices, found objectionable.

Martin Van Buren, who opposed Clay and Adams, saw the debate as an opportunity to win the loyalty of the swing states, divide New Englanders, and propel Jackson — his political ally — into the White House. He pushed Jackson's supporters in Congress to propose a bill that would raise tariffs on the raw-material imports, believing that if it passed, Jackson could claim credit and win the support of the Midwestern and Mid-Atlantic swing states, while if it failed, Jackson could paint Adams and Clay as enemies of those states. All the while, he promised Southern opponents of tariffs that no such bill could ever make it through Congress — or if it did, that Adams was sure to veto it.

The final legislation increased rates on raw-material imports and, thanks to amendments from New England senators, included protections for manufacturers that would mitigate some of the higher costs of the tariffs. Representatives from the Midwestern and Mid-Atlantic states voted heavily in favor of the bill, while the Southern states voted largely against it. In the end, the measure garnered enough votes from the New England states to push it over the edge, and Adams signed it into law. It was thus Van Buren's political scheme, not Clay's grand vision, that carried the day.

The debate over the plan in New England was conducted along the same lines as the earlier disputes between Hamilton and Jefferson. Textile manufacturers, who had grown stronger after the 1816 tariff, pushed for still higher tariffs to protect their industry from competition with textiles produced in England. They managed to win over key senators like Daniel Webster, even though it was not clear that the industry was still in its infancy. As the House Committee on Manufactures debated the bill, Delaware industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont testified:

[T]he woolen manufactory is not fairly established in this country, but I know no reason why we can not manufacture as well, and as cheap, as they can in England, except the difference in the price of labor, for which, in my opinion, we are fully compensated by other advantages....The high prices we pay for labor are, in my opinion, beneficial to the American manufacturer, as for those wages he gets a much better selection of hands, and those capable of, and willing to perform a much greater amount of labor in a given time.

The New England debate should give pause to national-security conservatives who assume industrial planning will protect security interests. In 1828, Britain was easily the greatest threat to American national security. Alone among the powers of the world, it had the fiscal resources and naval power to not only blockade the United States, but to invade and occupy any location in the country accessible by water. At a time when transportation over land was vastly more costly than transportation over water — transporting a ton of goods 30 miles over land cost as much as transporting the same cargo 3,000 miles across an ocean — nearly every economically significant part of the country was open to British assault. The United States had fought two wars with Britain and barely held on thanks to France tying up the overwhelming majority of British resources and attention. If America were to become entangled in another war with the mother country, it could easily find itself alone and vulnerable. Any statesmanlike industrial policy would have focused on protecting the country from the British threat, but that is not what the architects of the 1828 tariff had in mind.

To compound the difficulty, Congress refused to allocate the resources the U.S. Navy needed to defend the nation. British leaders had known for decades that concentrated fleets of large warships were the most effective way to command the seas and fend off rival fleets, but American strategists thought the country's lengthy coastline made concentration a losing strategy — there was no guarantee, after all, that the American fleet could locate an invading fleet, let alone defeat it. Instead, they preferred to mobilize America's merchant fleet to attack British shipping all over the world, with the intent of imposing high enough costs to force London to negotiate a settlement. This plan had failed in the War of 1812, but it was the only one available without enormous increases in naval funding. The merchant fleet was thus not only an important economic actor, but vital to national security. And yet it received less consideration from Congress than did molasses refiners.

The 1828 tariff helped usher in the presidency of Andrew Jackson, who tore up Hamilton's institutions and set the country on a path of relatively low tariffs and state-led infrastructure spending for the next 30 years. Between 1787 and 1860, the federal government spent $54 million on infrastructure — an amount dwarfed by the states' collective $450 million.

And yet despite the lack of leadership from Washington — or perhaps because of it — the nation prospered. Even before the Civil War set off a railroad boom, the United States had constructed more miles of track than France, Great Britain, and the German states. According to the most comprehensive figures from the Maddison Project, the United States' GDP surpassed Great Britain's in 1862. And though the United States had the larger population, its per-capita GDP hovered between 82% and 93% of Britain's at the time. By comparison, in 2018, Germany's per-capita GDP was 83% of the United States' GDP. So while Hamilton's and Clay's nationalist policies might have had the same result, they either never made it through Congress or failed to survive the political environment — and the American economy flourished all the same.

IS HISTORY BUNK?

This is all very nice, a supporter of a nationalized industrial policy might say, but past performance is no guarantee of future results. While previous attempts may have failed, the next attempt could succeed.

An optimist might posit that after 200 years of reform and accumulated wisdom, American governing institutions are better equipped to create and implement a productive industrial policy than they were in earlier eras. After all, Jackson didn't merely bring an end to America's Hamiltonian moment; he also inaugurated the spoils system that politicized civil-service appointments and fostered massive corruption. But the Pendleton Act and other measures have since reformed the civil service, making it much more meritocratic than it was during and immediately after Jackson's presidency. If the United States can override the Jacksonian spoils system, why can't it do away with more petty corruptions?

Moreover, unilateral industrial planning is far easier today than it once was. Progressive reformers of the early 20th century streamlined lawmaking power by establishing federal agencies and granting them extensive regulatory authority. Since then, Congress has delegated much of its lawmaking responsibility to these executive-branch entities, while the Supreme Court remains hesitant to disturb precedents that enable the legislature to contract out its duties in such a manner. With a legislative branch no longer interested in legislating and a judiciary reluctant to adopt more rigorous separation-of-powers doctrines, the president can re-order the American economy practically at will.

And yet despite these changes, there is no reason to believe that today's executive branch has either the vision or the competence to carry off the kind of policy leadership that industrial planners wish to see.

One of the most important implementers of federal industrial policy in the modern age is the Department of Defense. If there ever was a test case for the statesman view, this is it. The Pentagon is filled with members of the military who swear oaths to obey lawful orders given by their superiors, and the department itself has a well-defined mission: "to provide the military forces needed to deter and win wars and to protect the security of our country and our allies." This is obviously a complicated task, but it is no more daunting than correctly identifying the key determinants of economic power and ensuring American dominance of them — which is the essence of industrial planning.

Through agencies like the Office of Industrial Policy, the department monitors and supports parts of the American economy that produce military supplies or can be mobilized in the event of war or other emergencies. It does so primarily through two methods: by funding research and development, and through defense procurement. In part because of notable successes, particularly during the Cold War, the funding of research and development is one of the most popular forms of industrial policy available to policymakers. Defense procurement, on the other hand, is a parade of horrors, illustrating the greatest weakness of more aggressive forms of industrial policy: Much of the money spent will be wasted, and deliberately so.

Congress may have given away much of its power, but it keeps a tight hold on the policy levers it cares about most, including discretionary spending. And while our representatives are patriots who love their country and want a strong defense, they are also keenly interested in making sure their constituents are paid to provide that defense. This dynamic does not make for efficient or enlightened policy.

Apportioning out military spending to multiple constituencies has always been part of American defense policy. During Washington's presidency, Congress approved funding for six frigates to protect American shipping, particularly from pirates supported by the North African states. By miraculous happenstance, the administration determined that each frigate needed to be built at a different shipyard, and the materials to build them needed to be procured from locales across the country. As naval historians Harold and Margaret Sprout put it, "there is every indication that the Administration deliberately spread its shipbuilding operations over as large an area, and among as many individuals and companies as possible. It is also evident that home industries were patronized as much as possible." The frigates ultimately cost 70% more than anticipated.

The modern defense industry is plagued by the same kind of political engineering and its associated cost overruns. The problem is easiest to observe in major acquisition projects like aircraft carriers and jets. Today's aircraft carriers are built and maintained by over 2,000 firms scattered across 46 states. One of the newest carriers, the U.S.S. Gerald R. Ford, cost $2.8 billion more than originally budgeted. Lockheed Martin sourced parts for the F-22 stealth fighter from over 1,000 suppliers across 44 states — doubtlessly to provide the U.S. Air Force with the greatest capabilities at the lowest possible cost. Similarly, F-35 fighters are being built in 45 states as well as Puerto Rico. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Congress frequently requires the Defense Department to purchase more F-35s than the Pentagon requests. All of this prompted the late senator John McCain to denounce the F-35 program as "a scandal and a tragedy with respect to cost, schedule and performance."

Military-base policy is another area where parochial interests crowd out national priorities. Bringing well-paying jobs to economically underperforming parts of the country is a commonly cited objective among would-be industrial planners, and maintaining military bases in those locales is one way of meeting that goal. Unfortunately, Congress employs this strategy far too zealously, and our national defense is poorer for it.

The American military shrank in the late 1980s and early 1990s as the Cold War drew to a close, leaving some bases nearly empty. Defense experts have advised that these bases be closed to free up spending for other programs, and the Base Closure and Realignment Act of 1990 established a process for doing so. Reducing the base-operations support budget by around 20% would free up about $5 billion annually — enough to fund two additional aircraft carriers, their associated aircraft, and three attack submarines or surface ships. But such reductions rarely happen in reality. Even empty bases provide employment, and since no member of Congress can stomach putting his constituents out of work, the Pentagon still pays for more bases than it needs.

Creating a civilian reserve capacity to mobilize in emergencies is another proposed goal for industrial-policy advocates. But earlier attempts to do so have become entrenched, and now they actively harm national security. A famous example is the Jones Act, which requires cargo shipped between parts of the United States to be carried on vessels built, owned, and crewed by Americans. The act, passed in 1920, was intended to preserve the American merchant marine and keep in place spare shipbuilding capacity for war at a time when American-built ships cost 20% more than foreign ones. A century later, American-made tanker ships are nearly 400% more expensive than foreign-made ones. And yet the Jones Act remains in place. As a result, American civilian shipyards cater almost exclusively to clients held captive by the Jones Act's requirements: Between 2007 and 2017, over 900 ships were built in the United States, but only 80 were exported. Since the act sustains 650,000 American jobs in various congressional districts, repealing it is a political non-starter.

Perhaps the cost would be worthwhile if American civilian shipbuilders were experimenting with new and expensive technologies. But as a study by the National Defense University found, U.S. shipbuilding is "an average of twenty years behind international shipyards regarding advanced technology." The bottom line is that protecting a company from market forces or foreigners' predatory actions while also forcing it to keep pace with its competitors is nearly impossible — particularly once legislation creates a constituency to keep that company from going under.

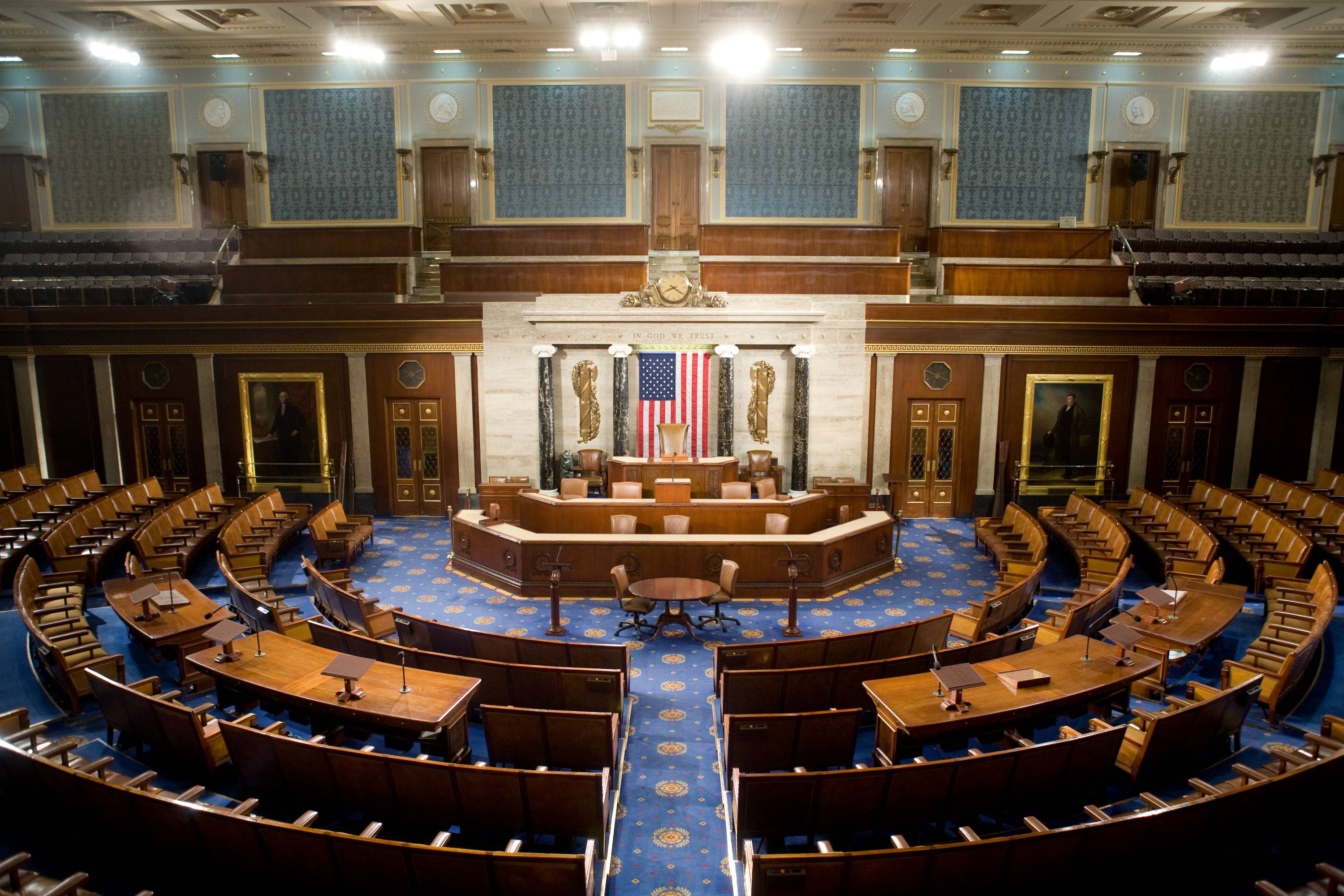

Given the nature of industrial policymaking in the United States, there's little reason to believe future attempts at industrial planning will result in a more coherent, rational, or strategic allocation of resources than they have in the past. The American system deliberately divides federal (and state) policymaking power and distributes it among hundreds of officials in separate branches. These branches have distinct priorities and interests, and the officials who populate them are influenced by political and parochial calculations as much as — or in some cases, more so than — perceptions of national interest. In short, industrial policy in the United States cannot be steered by a small group of enlightened individuals, because a small group of enlightened individuals will never be at the helm. Indeed, in some sense, there is no single "helm" to speak of.

BUILDING ALLIANCES

Despite the burst of creative energy among manufacturing advocates and national-security conservatives, the two forces have yet to overtake the Republican Party. Significant portions of the party's House and Senate delegations, as well as the right-leaning policy community more generally, remain devoted to the Reagan-era platform of low taxes, free trade, and a business-friendly regulatory environment. They harbor deep concerns over a national industrial policy, which they fear may usher in the kind of stagnation that plagued the U.S. economy in the 1970s.

While this pro-business contingent still defines most of the GOP's actual agenda, it's not yet clear which of the three factions will ultimately be the Republican standard-bearer in the coming decades. What is clear is that in order to achieve or maintain electoral viability, at least two of the factions will need to join forces. To clarify the dilemma ahead for the Republican Party, and for the country at large, it is helpful to examine the potential alliances between the factions on the right, their electoral-viability prospects, and their industrial-policy implications.

Many observers assume manufacturing advocates and national-security conservatives can achieve their respective objectives by working hand in hand on industrial policy. Sensing this natural common ground, elements of the pro-manufacturing right have already begun actively courting defense hawks. Senator Marco Rubio, one of the most prominent manufacturing advocates in Congress, has attempted to make common cause with his colleagues by framing his industrial-policy arguments in terms of national security. "The market," he insists, "will always reach the most efficient economic outcome, but sometimes the most efficient outcome is at odds with the common good and the national interest."

National-security conservatives may be inclined to accept the embrace offered by their pro-manufacturing suitors, yet they risk compromising their objectives if they do. From a defense perspective, maintaining the U.S. economy's competitiveness is as important as maintaining the military balance of power in the Pacific, and the policies pushed by the pro-manufacturing crowd may cultivate too much dead weight for the American economy to handle. Manufacturing advocates may talk frequently about the investment and innovation benefits that the manufacturing industry creates, but those mainly apply to new, high-productivity sectors that rarely provide the kind of mass employment these advocates desire. As Vaclav Smil notes in his book Made in the USA: The Rise and Retreat of American Manufacturing, the three domestic manufacturing sectors that have experienced "recent employment losses surpassing half a million jobs" are textiles, motor vehicles and parts, and apparel. T-shirts and shoes are hardly the key to a high-tech future. They are certainly not priorities for national-security conservatives.

What's more, defense requirements and manufacturing efforts can sometimes work at cross-purposes. Steel is vital for any serious defense-oriented industrial policy: Without reliable sources of the material, the United States would rely on foreign companies to build aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines, and other weapons systems crucial for our national security. But for manufacturing advocates, the steel industry poses tough questions. Steel manufacturing only provides between 15% and 25% of the jobs it did 60 years ago, and steel tariffs tend to destroy more manufacturing jobs in industries that use steel than are saved in steel mills. Thus the domestic benefits of attempting to protect and prop up the American steel industry may be outweighed by the costs.

Alternatively, national-security conservatives could jettison the manufacturing wing of the party and ally themselves with the business community. Such a coalition would resemble the previous Republican economic consensus most closely — and contain all of its promises and pitfalls. The arrangement would push the party toward policies that support big-tech firms, especially those in Silicon Valley, and maintaining a light-regulation framework would be necessary to appease this bloc. However, some compromises would have to be made to reduce Chinese access to cutting-edge technologies, encourage domestic semiconductor manufacturing, and secure supply chains for American electronics — all of which are priorities for defense-oriented conservatives.

The business and defense communities may gravitate toward each other on many issues, but they may repel too many voters to survive politically. The corporate reactions to policies like the North Carolina bathroom bill and recent election-reform measures in Georgia suggest many of the issues that most excite Republican populists — a large and highly influential portion of the electorate on the right — horrify corporate officers. Meanwhile, the populists are just as horrified by the seemingly cozy relationship between big corporations and increasingly radical social progressives, and are eager to take on Silicon Valley for stifling conservative voices.

Moreover, even if a business-defense alliance were to stimulate job creation, it may not mandate enough jobs to placate the populists. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company operates about half of the world's semiconductor foundries and employs about 50,000 people. Replicating the industry in its entirety in the United States would not be enough to restore the Rust Belt.

A final option is for the business wing of the party to meet manufacturing advocates halfway. Readers of a certain age may recall that the Republican Party was the party of protectionism until the business community embraced free trade. If pro-business Republicans were to accept moderate subsidies and protectionist tariffs for the Rust Belt as necessary for the country's political health, some of their congressional allies might follow suit. After all, even Senator Roger Wicker, an industrial-policy skeptic, is an ardent supporter of the Jones Act — as is every Mississippi politician who enjoys his job and wants to keep it.

Of course, a business-industrialist alliance risks creating the worst of all worlds, with the entire American economy becoming as unproductive and uncompetitive as its shipbuilding industry. And yet an entirely free market would not be ideal, either. As geopolitical competition sharpens and national-security threats become more varied and severe, prudence demands we maintain our economic and military edge while addressing the valid complaints that drive populist agitation. The only question is how to find a balance among these competing concerns.

In that regard, the country's earliest Republicans might offer a path forward for the party today. Like Hamilton, the Republicans of the Lincoln era boosted the cutting-edge industries of their time. Yet unlike their Federalist forebears, they consistently won elections because they also championed agriculture, a sector of the economy that remained popular even as it lurched toward insolvency. Through policies like the Homestead Act, they found ways to subsidize single-family farms — the American Dream of the time — without crippling the railroads or other burgeoning industries. In a similar fashion, moderate concessions by today's business community and national-security hawks to manufacturing advocates might placate restive voters while generating enough economic dynamism to keep America safe and prosperous.

A MULTITUDE OF STATESMEN

American political institutions do not make coherent and enlightened policies easily. To gain approval, any attempt to introduce discipline into the economy will require carve outs and concessions that, if not tempered, could make a mockery of the ostensible objective. Policymakers should thus be exceedingly cautious about any attempts to re-orient the American economy from the top down.

Government intervention in the American economy is akin to adding chlorine to a pool. Without enough chlorine, swimmers can catch waterborne diseases, and the pool will become filthy and unusable. Yet too much chlorine will damage swimmers' lungs and blister their skin, leaving them sicker and more vulnerable than before. Similarly, without some protections, the country will grow weak and lose the means to defend itself. But excessive industrial planning will drag down the economy — and with it, our capacity to maintain dominance in the international sphere.

Ideally, there would be a coherent strategy for adding chlorine to the pool and ensuring that the right concentration remains over time. But in the American system, there is no single statesman who can dole out the proper amount of chlorine at will. Championing a political program premised on enlightened statesmen accurately identifying and consistently pursuing the national interest is thus a mug's game.

Planners may dream of a new Hamiltonian moment, but they do so in vain. This is still Van Buren's world, and we must act accordingly.