How to Fix the House of Representatives

A few months after he resigned as speaker of the House, John Boehner walked into Pete's Diner, one of his old haunts on Capitol Hill, and said something I will never forget. I was eating breakfast with Congressman Mike Kelly, a fellow Notre Dame alumnus whose district bordered mine. Boehner walked right over to us, looked at me and deadpanned, "what's wrong with you? Same shit, different speaker?"

We had a great laugh. But whether he intended it to or not, Boehner's question revealed just how broken Congress was. And this was back in 2016.

Of course, Congress's troubles didn't start then, either. The institution had been broken for some time, and it remains broken to this day. After six years as a member, witnessing how the House operates from the inside, I have come to believe the roots of Congress's dysfunction lie in our abandoning the framers' plan for the national legislature. This abandonment, in turn, contributes to polarization and Americans' estrangement from the national government.

The defects can be separated into three categories: substantive, procedural, and structural. The substantive problems relate to the atrophying of Congress's legislative power. The procedural problems relate to how the House is run, specifically with respect to how legislation is crafted and how the House calendar deforms the institution's work. The structural problems concern the size of the House. These sets of problems are related, but each should also be understood on its own terms.

CONGRESSIONAL DERELICTION

Our country was founded on four fundamental, revolutionary principles: that God created all humans as equals; that he endowed them with certain fundamental rights; that to secure these rights, people establish governments; and that governments govern justly only when their authority is based on popular consent. These principles ring out clearly in our Declaration of Independence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

The founders, acting as representatives of the people, constructed a framework of governing institutions atop these principles and authorized them to exercise the legislative, executive, and judicial powers necessary to govern the country. In doing so, they granted America's political institutions the ability to act based on the consent of the American people.

At the same time, the founders remained keenly aware of how the newly empowered federal government could threaten the people's right to govern themselves. To prevent the nation's governing institutions from becoming powerful enough to overwhelm the people's sovereignty, the founders divided the federal government into three separate branches. They then distributed the authority to wield the limited and specific powers assigned to the federal government among those branches, established various methods by which the branches would be compelled to check one another, and then authorized the people to check them all.

The legislative branch, which exercises "[a]ll legislative Powers" bestowed upon the federal government, is where the people's sovereignty is most palpable. It consists of a Congress separated into two chambers: the House of Representatives, and the Senate. Originally, the members of each chamber were chosen via different methods — the House's members were selected through direct elections by the people, and the Senate's were appointed by state legislatures. In 1913, the 17th Amendment shifted the power of electing senators to the people, so that today, all House seats and a third of the Senate's seats are up for election every two years. This arrangement makes the legislative branch far more representative of the people than the other two branches.

Unlike Congress, the executive branch is run by a single individual: the president of the United States. He is subject to public consent indirectly through the Electoral College. The electors who make up the Electoral College are chosen by political parties at the state level, and the number of electors each state receives is equivalent to the total number of members it has in Congress. Every four years, the people of the individual states vote for president by voting for their presidential candidate's preferred electors. In most states, electors are awarded to the candidate based on the winner of the state's popular vote.

Though the president (and vice president) are elected to office by the people, the Electoral College creates a kind of buffer between the president and his constituents. This design was intentional, as the founders were exceedingly suspicious of direct democracy. The remainder of the executive branch — which consists of cabinet secretaries, heads of sub-agencies and bureaus, commissioners of independent agencies, and various board and committee members, as well as the officials and staff that serve them — is subject to popular consent only indirectly, via congressional oversight and the president's orders. As a result, executive bureaucrats are largely insulated from public accountability.

The judiciary is the third and final branch of the federal government. The judges who make up the federal judiciary are not directly answerable to the public, as they do not run for election and serve for lifelong terms. However, judges are indirectly subject to popular consent in that the people have a say in selecting the president, who appoints federal judges to the bench, and in electing senators, who confirm the president's appointees. A judge may also be subject to indirect popular oversight through the House's impeachment and the Senate's removal powers.

The founders' framework of divided powers and popular consent gave the American people some control over those who make the laws that govern them, with the degree of control varying based on the branch. Yet the people's influence has waned in our time. This development is most directly traceable to the fact that their representatives in Congress have abdicated, delegated, or otherwise failed to defend their lawmaking authority. Meanwhile, the executive branch has stepped into the lawmaking vacuum — in many cases at the behest of Congress itself. One of the most conspicuous consequences of this shift in authority has been the proliferation of executive entities that now govern broad swaths of American life. These agencies exercise regulatory (i.e., lawmaking) powers, in addition to enforcement and adjudicatory powers.

Such an arrangement ignores James Madison's admonition in Federalist 47 that "[t]he accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands...may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny" — a statement that encapsulates the impetus behind the founders' decision to divide the legislative, executive, and judicial powers granted to the federal government among the three branches.

To help ensure these powers remained separate, the Supreme Court developed a judicial canon known as the "non-delegation doctrine," which limits Congress's ability to transfer its core legislative powers to any other branch. Unfortunately, judicial precedent has rendered the non-delegation doctrine all but toothless. Despite the rise of the administrative state since the New Deal, the Supreme Court has not struck down a congressional delegation of power to the executive branch since 1935. In some cases, the judiciary itself — which, by design, is even less subject to popular oversight than the executive branch — has invaded Congress's authority by rewriting, as opposed to upholding or invalidating, its laws. In doing so, judges have effectively taken on the role of legislators, while their rulings have absolved lawmakers of responsibility for shoddy lawmaking.

The executive branch's increased power has been a growing concern for decades. Ronald Reagan summarized the problem in his first inaugural address 40 years ago:

From time to time, we have been tempted to believe that society has become too complex to be managed by self-rule, that government by an elite group is superior to government for, by, and of the people. But if no one among us is capable of governing himself, then who among us has the capacity to govern someone else?

How did this "elite group" of the administrative state come to supplant the people's representatives in Congress? The process began during the late 19th century, when society's growing complexity convinced progressive reformers that the Constitution's framework was inadequate to serve the country's needs. They believed that experts and specialists, unrestrained by institutional checks and popular accountability, could do a better job of managing governing challenges than could the people acting through their elected representatives. This conviction has been a hallmark of progressivism since the turn of the 20th century.

Expanding the executive branch has offered progressives a workaround with respect to the Constitution's checks on federal power. Yet any efficiency gained has come at the expense of popular sovereignty — one of the foundational principles of a just government. The most glaring example comes in the form of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). Since it was established in 2010 under the Dodd-Frank financial reform law, the CFPB has been characterized as "the single most powerful and least accountable federal agency in American history."

The agency was initially run by a single director who could only be removed by the president for cause, as opposed to at will. While the Supreme Court struck down this restriction, there is still little to hold the CFPB accountable. It is not governed by a bipartisan board of commissioners, as is the case with other independent agencies. It also operates largely outside the congressional appropriations process, drawing its funds from a formula assessed against the Federal Reserve. And it takes a supermajority vote of the Financial Stability Oversight Council (an executive council of chief U.S. financial regulators, also created by Dodd-Frank) to overturn a CFPB ruling, which can only occur if the ruling is shown to threaten the safety and soundness of the American financial system. The agency thus stands largely on its own, free to make new laws, enforce those laws, and punish violations of those laws, all with little or no effective oversight by the people or their representatives.

The Constitution assigns all federal legislative powers to Congress for a reason: It is where the people's most direct representatives govern. If a member of Congress votes to enact laws of which the member's constituents do not approve, the people can replace the member in the next congressional election. Yet voters are largely powerless to remove agency bureaucrats who issue regulations or rulings they don't support. The only way they can exercise sovereignty over these bureaucrats is indirectly, by electing a new president. And even in that case, not all bureaucrats are political officials subject to appointment or removal by the president; many are career officials who remain in their positions even when the administration changes hands. The transfer of lawmaking power from Congress to the executive branch has thereby shielded a significant portion of federal lawmaking from popular consent.

If we want to return to a government by the people, we need those we elect to Congress to commit to keeping executive agencies on a short leash. A reform proposal that has percolated in Congress for several years offers an opportunity to do just that. Under the Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny (REINS) Act, if any federal agency proposes a regulation that has an impact of $100 million or more on the American economy, the regulation would need Congress's approval before it could take effect. This would give the people's representatives a chance to assess whether a proposed regulation is in the public's best interest.

Restoring some of Congress's lawmaking role through the REINS Act would not bring an end to rulemaking by executive agencies, or even roll it back. But it would offer greater oversight. If an elected representative makes the wrong call on a major regulation, he risks losing his job at the ballot box. This is how government by the consent of the governed is supposed to work.

The REINS Act is not the only way to restore the proper balance of power among the branches; Congress could also reel in executive agencies by limiting the degree of power it delegates to them in the first place. The non-delegation doctrine has been the subject of a revived debate in both the courts and academia in recent years; it even took center stage in the Supreme Court's 2019 decision in Gundy v. United States. While Justice Samuel Alito joined the Gundy majority in upholding Congress's delegation of discretionary authority to the attorney general through the law under dispute, his concurrence left open the possibility of the justices re-assessing the way the Court applies the doctrine to congressional delegations of lawmaking power. In a dissent, Justice Neil Gorsuch expressed hope that the Court would someday give greater scrutiny to these laws.

Ultimately, however, Congress cannot look to the courts to save it from the consequences of its own dereliction. The logic of both the REINS Act and a revitalized non-delegation doctrine assumes the congressional will to see them through — that is, it presumes there exists a desire among members of Congress to reclaim the institution's lost power. A recovery of that will is thus an essential prerequisite for recovering Congress's lead role in our constitutional order. Such a feat would become more plausible if the incentives confronting members of Congress were better aligned with the interests of the institution as a whole. Several procedural reforms could help make this happen.

THE ART OF LEGISLATING

About a year into my first term, after seeing several bills come to the floor without either going through a committee markup or receiving an opportunity for amendment, I had a conversation with then-majority leader Eric Cantor in which I expressed frustration about the manner in which legislation was being put together.

Cantor counseled that rather than focusing on the process, I should pay more attention to the overall policy wins we were achieving. His argument supposed I was content not only with the resulting policy (which I usually was), but with simply being a salesman to voters back home of a product in which I had virtually no input.

From my perspective, both policy and process are important. And they are deeply intertwined: Policy takes shape within a process, and if the process is a closed one, very few members will see themselves as lawmakers. This can't help but deform not only how they work as members of Congress, but also how they understand the purpose and role of the institution itself.

Broadly speaking, for a bill that starts in the House, regular order begins when a member puts a bill into the hopper on the House floor. There, the bill is referred to the appropriate committee or committees. The chair of the relevant committee decides whether the bill will be taken up, and may assign it to a subcommittee. Either the subcommittee, the whole committee, or both, hold hearings to review the bill's merits. If the chair so chooses, the bill may be scheduled for a markup before the whole committee, whereby committee members prepare the bill for floor consideration. During markup, members may propose amendments, which are subsequently debated and put to a vote. A final vote on the whole bill as amended is then taken within the committee.

If a bill passes the committee, it still needs approval from House leadership to reach the floor. As long as House leaders support the bill, it will be scheduled for floor debate as either a suspension bill or a rule bill. Suspension bills are those that bypass the Rules Committee and head straight to the floor, provided they receive a two-thirds affirmative vote in the House. If this does not occur, the bill is sent to the Rules Committee, which proposes a resolution, or rule, that prescribes how the bill will be debated on the floor — including whether any amendments may be proposed.

The committee-markup and floor-amendment processes offer the only opportunities for rank-and-file members to have a say on what a bill contains. Nowadays, bills often bypass committee hearings altogether. And given the way the Rules Committee is run, the chances of a member having an amendment considered on the floor is becoming increasingly rare.

Limiting member engagement on legislation reached a low point in 2020 with the drafting of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. At a cost of $2.2 trillion, this was the largest spending bill the House had ever considered. Yet only a handful of the House's 435 members had any substantive input on the legislation. The bill was never marked up in a committee hearing, there was no opportunity for members to offer or debate amendments, and the one member who suggested there should be a recorded vote on the bill was widely condemned.

Though the CARES Act was taken up under emergency circumstances, the same pattern plays out all too frequently. It happened just two years earlier in the context of the perennial debate over immigration. In June of that year, the House voted on two bills, which were referred to as "Goodlatte I" and "Goodlatte II" in reference to Bob Goodlatte, then-chairman of the Judiciary Committee. Ironically, neither bill was sent through the Judiciary Committee — or any committee, for that matter. There was no chance for members to develop the record, no chance for them to offer amendments, no chance to build support for the bill, and no chance to negotiate a compromise. In the end, neither Goodlatte I nor Goodlatte II passed the House.

Bypassing the committee and amendment processes disenfranchises members and the people they represent. It precludes debate on issues members may want to bring to the fore on behalf of their constituents. And it bottles up tension in our political system, resulting in frustration and resentment on both sides of the aisle.

A more open process would produce legislation that more closely resembles the will of the House — and in turn, the American people — as a whole. Of course, opening up the legislative process to member input has its drawbacks. One of the primary motivations behind the closed process is that it gives leadership more control over which issues are brought to the floor. A speaker might prohibit amendments on a bill, or even prevent bills from being debated or voted on at all, in order to keep fellow party members from having to take tough stands on hot-button issues, which puts them at risk of losing re-election. Protecting members' seats in this manner protects the party's majority status.

But this strategy begs the question of what is gained by achieving majority status in the first place. If members of the majority party cannot debate, negotiate, and ultimately pass legislation on controversial issues, there is little reason for the party to hold a majority at all. More fundamentally, the people's representatives in government have an obligation as statesmen to address the difficult issues confronting our nation. By shirking one of the primary duties of the job, they are failing to live up to their oaths as legislators.

A more practical critique is that allowing members to mark up bills and offer amendments gives opponents of a bill the chance to inject "poison pill" provisions into the text. Poison-pill provisions are amendments designed to undermine support for the legislation as a whole. Enabling such bad-faith activity is a risk inherent to a more open legislative process, but there is a viable solution: Members could be allowed to propose amendments to amendments, granting them the opportunity to alter poison-pill provisions. Such a process would not only require further openness, it may even produce better legislation.

The art of legislating is lost when debate is short-circuited. It's time to re-invigorate that art. As a threshold procedural reform, House rules should prohibit, absent a true emergency, any legislation from coming to the floor unless it was marked up in an open amendment process and then approved by the appropriate committee, or was brought directly to the floor via discharge petition signed by a majority of House members. Such requirements would give substantive meaning to the concept of "regular order" in Congress.

Additionally, the art of legislating — if done correctly — requires extended floor time. Yet the House's legislative calendar makes it difficult for members to do the actual work of crafting the nation's laws. Having lived through this schedule for three terms and witnessing what has taken place since then, I can confidently attest to the fact that this calendar contributes to the House's dysfunction. Some of the most obvious illustrations include repeated failures to complete the appropriations process in a timely manner as well as members' failures to adequately review legislation. Having more legislative days, and fewer breaks in between them, would contribute to better lawmaking outcomes.

Each Congress sits for two sessions over two years, with the first session taking place the year after the congressional election and the second the year after that. While each session of Congress spans approximately 365 days, after excluding weekends and the 10 federal holidays, there are only 250 business days per year for members to build a congressional work schedule. The House is in session for fewer than half of those days.

Moreover, with the typical 3.5-day legislative work week on Capitol Hill, members generally return to their district every weekend. For weeks that run Monday through Thursday (some weeks run Tuesday through Friday), members meet at the Capitol on Monday for votes at 6:30 P.M. Tuesdays and Wednesdays are full of committee hearings, constituent meetings, floor debates, and votes, followed by receptions, dinners, and study time. There may be additional hearings on Thursday morning, with votes around noon. Then it's off to the airport for the flight home.

The frequency of these long weekends encourages members to spend time apart from one another, which makes it difficult for them to build the kinds of personal connections that grease the skids of the legislative process. This contributes to the trouble rank-and-file members have in building coalitions to pursue objectives that may not be consistent with what their party leadership is prioritizing.

Like the centralized lawmaking process, this arrangement empowers House leadership, along with committee staff and lobbyists — all of whom oppose changing the existing calendar. But the lawmaking process suffers as a result. During the GOP organizational conference for the 115th Congress, I proposed a rule to require the House to approve the legislative calendar in hopes of breaking the leadership's hold on the schedule. Unfortunately, the measure did not pass.

A calendar more conducive to a legislative culture grounded in deliberation and negotiation would have Congress in session between its opening on January 3 and the Independence Day holiday. There would likely be a break around Easter and Passover, but by and large, House members would be working Monday through Friday for the better part of six months. Members would still be able to fly home Friday evenings, but they would need to return to the Capitol by Monday for committee hearings held during the day, making the weekends less conducive to long trips away from D.C.

With the House in session for the first six months of the year, there would be room for an extended summer recess, allowing members to work in their districts between Independence Day and Labor Day. This would work especially well for members with children, since many parts of the country send students home for the summer and back to school as early as the beginning of August. The House would reconvene immediately after Labor Day and remain in session until work is done for the year, with a break for the Jewish high holy days. If Congress were able to wrap up its work by Thanksgiving, the month of December could offer lawmakers another extended work period in their districts.

Critics may suggest that the calendar proposed here would limit members' contacts with their families, their constituents, and their donors. Those concerns have merit, but they could be accommodated by allowing for intermittent three-day district weekends, or by providing members with resources that would permit their families to travel to Washington for extended visits. The primary goal of the calendar, however, should be giving members the tools to serve the interests of the American people rather than those of the Washington establishment, and the changes I've outlined above do just that.

Such a schedule would also help diffuse polarization in our politics. If members had more time to debate the contentious issues of the day, they would be more inclined to become invested in their core legislative work. If members were forced to come into more frequent contact with one another, there would be greater opportunity for them to reach a consensus where possible. And if members were made to work throughout the week, those seeking celebrity status would have less time to devote to the kind of self-promotion that poisons the lawmaking process.

Procedural reforms like these could facilitate some of the more substantive reforms suggested earlier. But seeing them through will require us to consider other, more structural reforms. Right now, powerful forces of inertia prevent reformers from making even the simplest changes in how the House operates. Breaking that inertia will require a considerable push — one that will likely have to come directly from the people themselves.

RESTRUCTURING THE HOUSE

It has been over a century since lawmakers increased the number of seats in the House. In that time, our population has grown more than three-fold. It's well past time for the people's legislature to catch up.

The size of the House was debated at the founding, and in Federalist 55, Madison admitted that finding the right number would be an imprecise science. "[I]t may be remarked on this subject," he wrote, "that no political problem is less susceptible of a precise solution than that which relates to the number most convenient for a representative legislature." He nonetheless expressed confidence that Congress would add to the number of representatives as the nation expanded.

Madison's prediction remained the norm for 140 years. Our first Congress had 65 members to represent a population of 3.9 million, resulting in an average of one representative for every 60,000 Americans. When the population reached 23.2 million in 1850, Congress increased the number to 234, giving each member a constituency of roughly 99,000. By the 1900 census, there were 76.2 million Americans, and the number of representatives was raised to 386. This gave each member an average constituency of 197,000.

The current level of 435 members was set after the 1910 census. That year, 92.2 million Americans were counted, for a total of approximately 212,000 constituents per member. In 1929, Congress passed the Permanent Apportionment Act, which made the 435 cap permanent. And yet the American population has continued to swell. In 2010, 308.7 million Americans were counted, giving the average member of Congress 709,000 constituents. The recent 2020 census reported a population of roughly 331.4 million — an increase of 22.7 million since 2010. With the House remaining at its current size, the average congressional district is home to 762,000 persons.

The House is the federal body closest to the people. But as the nation continues to expand and the number of people represented by a single member increases, each American's voice in government grows smaller.

Expanding the House would amplify those voices in our national government, thereby returning a greater measure of sovereignty to the people. It would also have positive effects on more peripheral issues, including campaign finance, the diversity of thought in Congress, and the influence of special interests.

There is a cost associated with congressional campaigns. According to a January 2018 report from the Bipartisan Policy Center, "[t]he average amount spent by a winner of a House seat in 2014 dollars rose from just under $777,000 in 1986 to about $1.47 million in 2014, an increase of 89 percent." With our population projected to rise, the cost of reaching more voters will rise in tandem. Increasing the size of the House would help offset this escalating cost.

It would also help make Congress home to a greater diversity of thought. New members bring with them new perspectives and new ideas that may not conform to the orthodoxy of either party. Adding members could result in legislation that is more reflective of America's diversity, especially if combined with the calendar reforms described above.

To be sure, any legislation that passes the House would still need to pass the Senate and be signed by the president. But through expanded representation in the House, the American people would have a greater say in the final product than they do now.

Lastly, increasing the number of members in the House would dilute the influence of special interests on legislation. The more members there are in the House, the more difficult it is for lobbyists to capture a majority of members on any given bill. This would help liberate legislation from the grip of special interests and steer it more forcefully toward the public interest.

But what should the number of members be? Whatever quantity chosen will be unavoidably arbitrary in some respects, but as a starting point, I would propose a House of 601 members. Based on the 2020 census, this would give the average member a constituency of 551,000 persons — which is more in line with the constituencies of representatives in comparable democracies. If the United States had the same average number of residents per representative as other democracies in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development do, then the House should have around 593 members. The number I am proposing simply rounds that figure up to the nearest hundred, then adds one additional member to avoid tie votes.

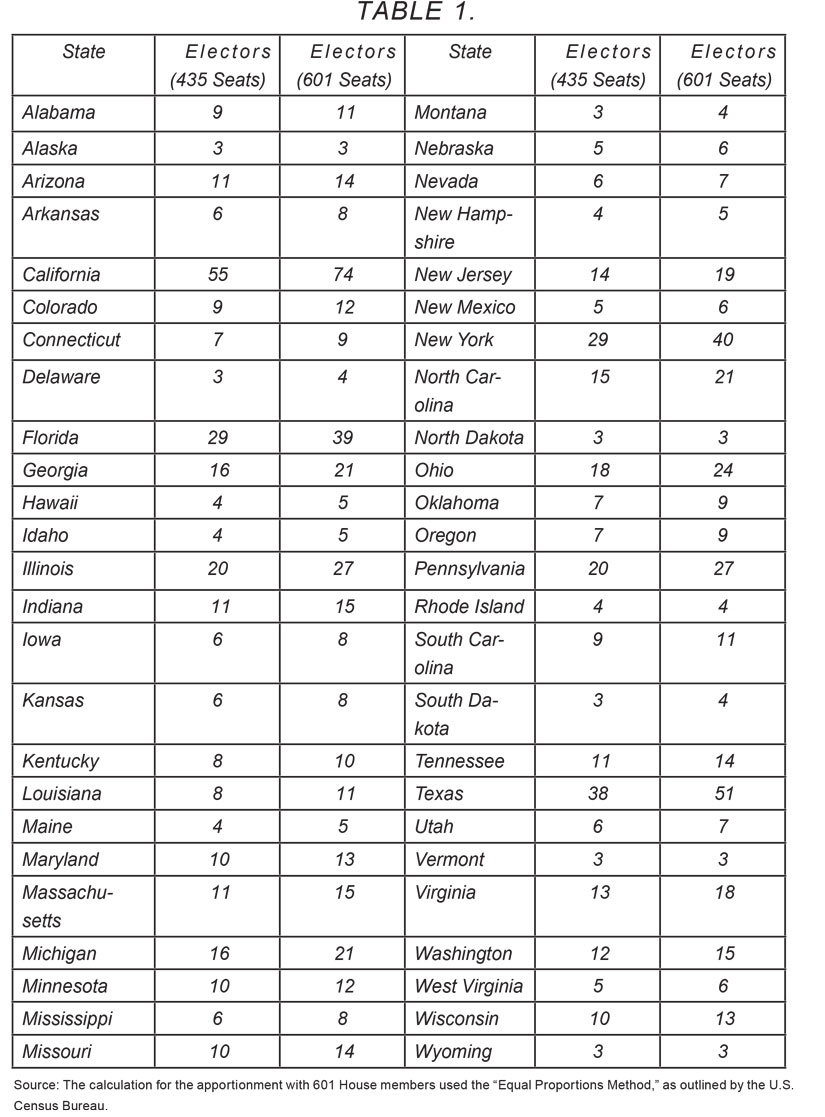

Changing the number of seats in the House would also affect the Electoral College, since each state receives the number of electors equal to the number of senators and representatives it has in Congress. With a House of 601 representatives and a Senate of 100, the Electoral College would consist of 704 electors (the additional three electors are from the District of Columbia). The following table shows how apportionment in the Electoral College would have looked during the 2010s with a House of that size.

To assess the impact that increasing the number of members in the House would have on the Electoral College, I evaluated whether any of the presidential elections since 1980 would have changed if there had been 601 representatives instead of 435. Table 2 compares how many electoral votes presidential candidates received with a 435-member House with what they would have received with a 601-member House.

As the table indicates, the only election that would have resulted in a different outcome was the razor-thin Electoral College victory George W. Bush secured over Al Gore in 2000. With an Electoral College based on 435 House members, Bush received 271 electoral votes and Gore received 267 — a four-vote margin in favor of Bush. If there had been 601 House members that year, Gore would have eked out an Electoral College win by the same number of votes, winning 354 to 350.

Expanding the House is not a panacea for its troubles, of course. But it would help make the institution more representative. It might also serve as a shot in the arm for other reforms, providing an opportunity for members to change the calendar, the committee system, and the amendment process. In time, it may also help change Congress's attitude about itself.

REVIVING CONGRESS

The first two decades of the 21st century have presented our country with considerable challenges, including terrorist attacks, war, financial crises, racial and civil unrest, and a global pandemic. Many believe the nation is at a breaking point, or at least in the midst of a significant cultural shift. As a result, American institutions, from government entities and churches to businesses and families, are under tremendous pressure to provide a path forward. A time like this calls for all our institutions — including the pre-eminent lawmaking institution of our system of government, the U.S. Congress — to adapt and recommit to their foundational principles.

The reforms identified above are not exhaustive — term limits, biennial budgets, and breaking up larger committees' jurisdictions are additional proposals worth considering. As long as the reforms pursued are targeted toward empowering the people's house, allowing representatives to give voice to their constituents' interests, and encouraging members to take back their lawmaking responsibilities, the restoration of the American constitutional order will be well underway.