The Weakness of Modern Monetary Theory

Less than a year before the novel coronavirus spread across the globe, Ray Dalio, Bridgewater Associates founder and billionaire intellectual, published an article on what he saw as the inevitable path for monetary, economic, and fiscal policy. In it, he partially endorsed a view that has emerged since the Great Recession: When monetary policy cannot provide further accommodation after nominal short-term interest rates hit the zero bound, additional fiscal spending is needed as stimulus.

This is not a particularly unusual position. Indeed, over the years, many mainstream Keynesian economists have expressed support for this approach — Harvard economist Lawrence Summers refers to it as "black hole" or "secular stagnation" economics. A year following Dalio's article, with Covid-19 cases and death tolls mounting, governments in major developed countries around the globe appeared to endorse this view, authorizing deficit-financed spending amounting to between 5% and 10% of gross domestic product (GDP).

Given that government-induced shutdowns designed to combat the spread of the virus contributed to unprecedented levels of unemployment, there was certainly a case for such measures. Dalio's article, however, put a radical twist on the traditional zero-lower-bound calls for more government spending by endorsing a novel, heterodox economic theory known as "modern monetary theory," or MMT. The defining feature of MMT — and what distinguishes it from more established, mainstream economic theories — is its insistence that, so long as a government's debt is denominated in its own currency, there is no upper limit on the state's monetary borrowing. In other words, public debt is irrelevant; a country's central bank can always avoid default by printing more money. Such printing, MMT proponents further argue, can go on without any inflationary consequences. They thus call for economists to shed their superstitious fear of debt and for policymakers to unleash the full power of unlimited, risk-free government spending.

It should come as no surprise that some of the loudest support for MMT in the United States comes from the progressive wing of the Democratic Party. After all, if measures of public debt signify nothing beyond future currency-production goals for the U.S. Treasury, then there is no real limit to the amount government can spend on massive programs like universal free college, a Green New Deal, a universal basic income, or a universal jobs guarantee. Moreover, in this moment of profound economic uncertainty, when policymakers are turning to deficit spending in hopes of averting complete financial meltdown, the apparent blank check that MMT advocates offer holds a certain appeal to panicked economists and legislators on both sides of the aisle.

Yet the sudden need for deficit spending in the wake of a global pandemic should not be used as an excuse to embrace MMT. While they may be convenient, MMT's central claims regarding the harmlessness of deficits, debt, and mass currency production are not only flatly false, they are deeply dangerous. Theoretical considerations and historical examples not only strongly undermine the central tenets of MMT, they also serve as a critical reminder to policymakers — particularly in a moment when deficit spending may truly be necessary — of what happens when governments fail, over long periods, to take responsible measures to balance their checkbooks throughout the business cycle.

GROWING OUT OF DEBT

MMT derives from a heterodox theory known as "chartalism," which emerged during the early 20th century as a rebuttal to the mainstream prevailing theory of money. According to the latter, money developed spontaneously as a medium of exchange because engaging in transactions through currency is more efficient than bartering. German economist Georg Friedrich Knapp challenged this theory in his 1905 book The State Theory of Money, arguing that money originated with states' attempts to direct economic activity. A given currency thus derives value not based on its status as a commodity — an object with either intrinsic or exchange value — but because taxes levied by a state are payable in the currency that the state issues.

Knapp's chartalist theory of money as "a creature of law" was echoed in John Maynard Keynes's Treatise on Money, in which Keynes asserted that money is "peculiarly a creation of the State." It appeared again in Russian-born British economist Abba Lerner's 1947 article bearing the title, "Money as a Creature of the State." Lerner also drew on chartalist theory to develop the concept of "functional finance," which suggests that because states can pay their debts by printing money, states with fiat currencies do not face any debt constraints when borrowing in their own currency. The only constraint they face, then, is that of inflation, which he argued is a result not of monetary policy, but of too much government spending. He also believed that inflation could be controlled by higher taxes, which would reduce the amount of money circulating in the economy.

In recent years, a few economic theorists who had previously described themselves as "post-Keynesian" in the vein of Lerner have revived chartalism as an explanation of money creation. William Mitchell, a professor of economics at the University of Newcastle, was the first to coin the phrase "modern monetary theory" in reference to this emerging school of thought. MMT builds on functional finance's removal of debt constraints on government borrowing. However, it diverges from Lerner's theory in at least one significant way: MMT theorists reject monetary policy's relevance to inflation.

According to MMT, then, governments can borrow and print as much of their own domestic currency as necessary without causing inflation. Consequently, MMT proponents like Dalio understand modern governments to be laboring under false and harmful assumptions regarding the threat of public debt.

To understand MMT's appeal — along with its theoretical flaws — it helps to understand macroeconomic theories of government debt. According to these theories, aside from default, there are only three ways to reduce such debt: first, by reducing fiscal deficits; second, through higher economic growth; and third, by using central banks to print money and monetize debt. The first option often gets the most attention from mainstream economists, while MMT proponents insist that governments pursue the third. Olivier Blanchard, a well-known macroeconomist and the 2018 president of the American Economic Association (AEA), recently drew the public's attention to the oft-neglected second option: a state's capacity to grow out of public debt.

In his AEA presidential address, Blanchard made a case for why debt "might not be so bad" as economists had previously assumed by arguing that the potential for economies to grow their way out of debt is less appreciated than it should be. He pointed to new evidence presented in his AEA presidential lecture, "Public Debt and Low Interest Rates," to back up his claims. Left-leaning economists like Harvard's Summers and Jason Furman have seized on such statements to argue that we need to worry less about government debt at present, as there is still ample fiscal space before we hit any meaningful limits on its sustainability. And yet despite these new findings — which may truly legitimize higher deficit spending — Blanchard acknowledges that there is still some limit to borrowing.

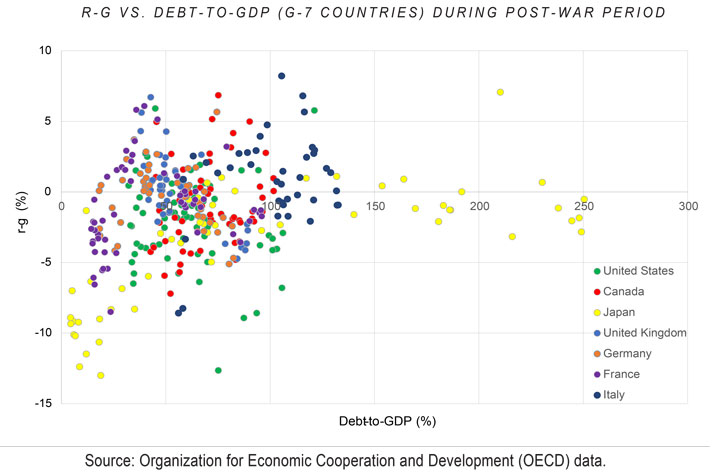

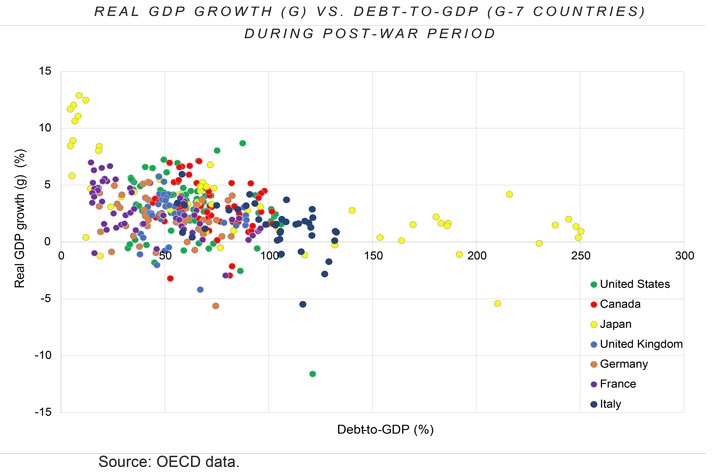

In arguing for greater debt toleration, Blanchard observes that for most of the post-war period, real GDP growth (g) has been higher than real interest rates (r). He further observes that when real growth is higher than real interest rates (i.e., r-g < 0), economies can grow their way out of an existing debt stock with relative ease as the higher tax revenues from higher g offset the growth of r.

To be sure, America has grown its way out of its debt stock in the past. In a 2018 New York Times column, Paul Krugman correctly observed that the United States did not pay back the debt accumulated from WWII through taxes or spending cuts. Instead, the nation grew its way out, something that it was able to do in part because real growth was higher than real interest rates for most of the 20th century and the country's debt-to-GDP ratio remained below 100%. Productivity growth was also much higher during that century, bringing more tax revenue to the government's coffers, as macroeconomists like Northwestern University's Robert Gordon have demonstrated.

But what if debt persistently grows at rates higher than g? In other words, is Blanchard's model scalable to even higher levels of debt-to-GDP? In short, the answer is no — at least not beyond a certain point. Annual values of r for the G-7 countries across higher levels of government debt-to-GDP show that, at higher levels of debt as a fraction of GDP, this beneficial r-g actually declines.

It thus appears the "Blanchard effect" — where r-g < 0 and nations can therefore grow out of debt — ends as debt-to-GDP reaches between 50% and 100%, depending on the country. The United States, which holds the world's reserve currency, appears to be at the higher end of that range, giving it more fiscal space.

What is causing the Blanchard effect to diminish as debt-to-GDP approaches 100%? More or less, it's the same story that Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff presented in their 2010 paper, "Growth in a Time of Debt," in which they observed that growth declines non-linearly with debt-to-GDP, hitting a flashpoint somewhere around the 100% mark.

In other words, lower growth at higher levels of government debt-to-GDP percentages makes it more difficult for an economy to grow its way out of a debt burden, thus diminishing the Blanchard effect. While there was some controversy surrounding data errors underlying Reinhart-Rogoff, and there remains debate over where the exact tipping point for government debt is, the empirical finding of an inverse relationship between real GDP growth and a government's debt-to-GDP ratio is very much a real one.

THE CONSTRAINTS ON DEBT

MMT proponents often point to the debt-to-GDP ratio in Japan at nearly 250% of GDP as a validation of their claim that deficits don't matter. However, as economists Mark Greenan and David Weinstein show, Japan has avoided a fiscal crisis by keeping its expenditures growth on social pensions and health care low while raising its value-added tax. Japan's central bank has also held short-term interest rates close to zero for decades while keeping long-term interest rates low by engaging in record rounds of long-term asset purchases of government bonds (an approach it calls "yield curve control"). If the path of interest rates in Japan were to change, interest costs would rise rapidly.

There are certainly special qualities that give the United States an added ability to borrow. For instance, financial economists Arvind Krishnamurthy and Annette Vissing-Jørgensen have demonstrated that the U.S. Treasury has a unique ability to borrow at lower rates, which arises in part because of the safety and liquidity benefits that come from its debt being issued in the world's reserve currency.

Yet this special quality does not eliminate the fact that, sooner or later, one does run out of other people's money. Eventually, interest costs on government debt become as large as the state's revenue, at which point investors, no longer believing the government to be solvent, will refuse to buy bonds or lend to the government at manageable interest rates. So while the United States almost certainly could stomach more debt at present, interest costs will eventually subsume all other government revenues. Interest rates being close to zero certainly slows down this process (and negative interest rates reverse it slightly), but once inflation eventually rises, so too will interest rates and the interest costs of public debt.

What the Blanchard example demonstrates is that, while there is plenty of room for economists to disagree about what levels of public debt are tolerable (even at levels higher than those at present), there still is an upper bound to the sustainability of government borrowing. Indeed, there is no doubt among mainstream economists that such an upper bound exists. Blanchard himself acknowledged its presence in a recent public rejection of MMT, saying "the deficit, unless very small, cannot be fully financed through non-interest bearing money creation, without leading to high or hyperinflation."

MMT advocates, however, deny the existence of this limit on debt printed in a government's own currency. They therefore embrace the third option for public-debt reduction — using central banks to print money and monetize debt.

MONEY PRINTING AND INFLATION

MMT proponents argue that central banks can print money without triggering dangerous levels of inflation. This claim not only overlooks the theoretical considerations outlined above, it also ignores the dark history of debt monetization leading to hyperinflation. As Thomas Sargent famously documented in his 1982 classic, The Ends of Four Big Inflations, printing money and monetizing debt — even when that debt was partly denominated in local currency — led to devastating inflation in Austria, Hungary, Poland, and Weimar Germany during the first half of the 20th century.

Austria and Hungary — two states formed through the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire — found themselves greatly diminished in both size and power following WWI. Since Austria-Hungary was deemed an aggressor of the war, its successor states owed the Allies substantial amounts in war reparations. To pay off the reparations while alleviating large-scale food shortages and unemployment, the Austrian government ran significant deficits — which it financed by selling treasury bills to the Austrian section of the liquidated Austro-Hungarian bank. At the same time in Hungary, political turmoil led to considerable budget shortfalls, which the government financed by borrowing heavily from the Hungarian section of the bank and increasing the volume of low-interest loans issued to private entities. As a result, both the Austrian crown and the Hungarian krone depreciated rapidly while domestic prices rose. This led to flight from each currency by domestic actors and foreign investors alike and, ultimately, to hyperinflation in both countries.

Poland, meanwhile, emerged from WWI as an independent nation after over a century of foreign rule. Cobbled together from portions of Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Russia, Poland inherited inflated currencies from these three partitioning powers — each of which had financed their respective participation in WWI through the printing press — and an empty treasury. The fighting in Poland did not end in 1918, either, as the nation found itself in a second war with Soviet Russia that lasted until the fall of 1920. In order to settle this and other border disputes, and to rebuild after the devastating WWI occupation, Poland amassed substantial debt. Like both Austria and Hungary, Poland financed its deficit spending by printing massive amounts of currency. In 1918, one U.S. dollar was equivalent to nine Polish marks; by the end of 1923, that same dollar was worth 6,375,000 Polish marks.

Of the four post-WWI cases of hyperinflation Sargent covers, none looms larger in the historical imagination than that of Weimar Germany. Germany had financed its war effort through deficit spending and suspension of the gold standard, believing that it would be able to achieve a swift, decisive victory and pay off its debt by annexing wealthier territories and imposing reparations on its defeated enemies. What occurred was very much the opposite: Over four long years of fighting, Germany accumulated considerable war debt while significantly devaluing its currency, the German mark. And since Germany was on the losing side of the war, instead of being paid reparations, it owed staggering levels of reparations to the Allies at the war's end.

Making matters worse, the Reparations Commission demanded Germany pay 132 billion gold marks as part of the London Payment Plan. The German government responded by printing more German marks to pay what it owed, which only devalued its currency further. In 1922, Germany failed to pay an installment it owed to France, which prompted the French occupation of Germany's primary industrial region to ensure repayment. The German government responded by calling for what amounted to a strike, then offered the workers financial support — again, financed by printing more currency and issuing loans at interest rates far below the rate of inflation. By 1923, German currency was worthless: One U.S. dollar at the time was equivalent to 4,210,500,000,000 German marks.

But hyperinflation is not just a phenomenon of the distant past. In fact, instances of hyperinflation have occurred over recent decades in countries like Brazil, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela.

Brazil experienced hyperinflation in the final decades of the 20th century. This resulted from its decision to pay down high external debt but avoid raising taxes. Instead, the country turned to printing money. By 1990, inflation reached a monthly rate as high as 82.4%. Hyperinflation in Brazil was only resolved when it created a separate unit of account, the Unidade Real de Valor, or URV, to exist parallel to its existing currency, the cruzeiro. Ultimately, this new unit of account became the Brazilian real, replacing the cruzeiro and quashing the inflationary spiral.

For Zimbabwe, the trouble began in the late 1990s, when the government adopted several spending plans — including the compulsory government purchase of white-owned commercial farms and generous pension plans for veterans of the country's war of independence — without budgeting for them. This triggered panic among foreign investors, who pulled capital from the Zimbabwean markets, thereby causing a crash of the country's currency.

Subsequent unwise military ventures drove Zimbabwe further into debt. Meanwhile, the forced seizure of farmland and resulting violence nearly halted all agricultural production. Since the Zimbabwean economy was too fragile to grow its way out of debt, and imposing new taxes to raise revenue was a political non-starter, monetary and fiscal authorities began to monetize the country's debt by printing more money. This ultimately led to hyperinflation so extreme — at an estimated 79,000,000,000% per month in November 2008 — that Zimbabwe was effectively forced to substitute its own currency with the U.S. dollar shortly thereafter through a process economists call "dollarization."

The seeds of Venezuela's ongoing struggles with hyperinflation were sown in the early 2000s, when the nation's economy and the value of its currency, the bolívar, became heavily dependent on revenues from oil exports. The rise in oil prices that largely coincided with President Hugo Chávez's term in office — from 1998 until his death in 2013 — ensured a steady stream of foreign revenue into government coffers. This allowed the Chávez regime to increase deficit spending in pursuit of its socialist policy agenda.

Then in 2014 — a year after Chávez's successor, Nicolás Maduro, took office — the global price of oil collapsed, leading to a steep decline in government revenues. Foreign demand for the bolívar to purchase Venezuelan oil fell, contributing to a decline in the currency's value. The Venezuelan economy was already in recession at the time, but instead of pulling back on Chávez's generous social-welfare programs or increasing taxes, Maduro's regime responded by ramping up deficit spending and printing more currency to finance the government's debts. By 2016, hyperinflation had set in. At the end of 2018, inflation rates in Venezuela reached an estimated 80,000% per year.

As these examples demonstrate, the correlation between currency printing and hyperinflation is undeniable, the causal relationship intuitive. Yet MMT proponents continue to contest it. In their canonical MMT textbook Macroeconomics, William Mitchell, L. Randall Wray, and Martin Watts state that "[n]o simple proportionate relationship exists between rises in the money supply and rises in the general price level." Wray, a Bard College professor and one of MMT's key proponents in academia, has gone on to say "there is no empirical evidence to support the belief that raising interest rates fights inflation." Stephanie Kelton, author of The Deficit Myth and former advisor to Senator Bernie Sanders's presidential campaign, argues that inflation is the result, not of monetary policy, but of "overspending" — spending beyond what it takes for an economy to reach "full employment" (which she defines not according to the mainstream economic concept of "natural rate of unemployment," but as the 0% unemployment rate that would occur under a government jobs guarantee). Such claims fly in the face of both historical evidence and traditional macroeconomic theory. And it's worth remembering, too, that hyperinflation often hurts the poor the most, since consumption makes up a greater fraction of their incomes.

ECONOMIC THEORY OR POLITICAL MOVEMENT?

Since MMT was first developed, mainstream economists have repeatedly pointed out its flaws. A recent Chicago Booth IGM Forum survey of 50 of the most respected academic economists found that not a single respondent agreed with the central claims of MMT regarding deficits, currency production, or inflation. Even left-leaning Keynesian economists like Summers and Krugman have loudly denounced MMT claims as "dangerous" and "obviously indefensible," respectively.

Perhaps the strangest feature of MMT, then, is the simple fact that it has managed to develop the following it currently enjoys. Economics professors, billionaire thought leaders, and several members of Congress (including, most notably, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) have heaped lavish praise on MMT as the economic theory of the future.

So how does MMT live on? To start, many MMT economists have found financial support from billionaire backers like the late Leon Levy, who helped establish the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College that employs MMT economists to this day. More recently, Warren Mosler, a former hedge-fund manager and one of MMT's intellectual architects, co-founded and provided financial support for the Center for Full Employment and Price Stability at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, which also employs MMT economists. Yet with no serious mainstream economists stepping up to do anything other than attack MMT, how does this theory of economics continue to cultivate a base of high-profile supporters?

An answer to this question may have to do with the peculiar nature of MMT, which, upon closer inspection, appears to have more in common with a political or moral ideological movement than it does with a theory of economics. Like other ideologues, MMT advocates begin with the assertion that their policy goals — providing jobs for all, paying for college for all, etc. — are correct. From there, they assume that the means to achieve these ends must exist. This is not a falsifiable scientific theory; it is rather a political and moral statement by those who believe in the righteousness — and affordability — of unlimited government spending to achieve progressive ends. In this regard, MMT advocates have come to resemble mid-20th-century communists who argued that the Soviet Union could not possibly be a true socialist regime because a true socialist regime could only generate positive outcomes.

Beyond the mere absence of substantive arguments for their position, MMT advocates often obfuscate and redirect criticism rather than directly addressing it. Krugman has come to refer to attempts to engage MMT advocates as a game of "Calvinball" — a reference to the game played in the Calvin and Hobbes comic series in which the players constantly change the rules in transparently self-serving ways. Any time outsiders attempt to disparage or critically engage MMT, they are met not with a detailed rebuttal using empirical evidence or quantitative reasoning, but by MMT's advocates insisting the critics simply don't understand the theory. Krugman is not alone in his frustration: Mercatus Center economist Scott Sumner has said, "MMT has constructed such a bizarre, illogical, convoluted way of thinking about macro[economics] that it's almost impervious to attack."

This may sound like an unreasonable assessment of a theory that has found support among academics, entrepreneurs, and federal legislators. But the agendas of the annual MMT conferences held in New York serve as powerful evidence for its truth. Given all the criticism MMT has received from the economic establishment, one would think the conference would, like any other academic conference, be devoted to presenting empirical and theoretical studies, furthering research, and prompting serious scholarly debate. Instead, almost all MMT conference sessions have been based on political activism, with session titles such as "the future of jobs-guarantee advocacy," "building the jobs guarantee coalition," "MMT as an international movement," and "community strategy and institutional buildout." This makes MMT conferences look less like academic conferences and more like political conventions.

MOVING BEYOND MMT

MMT initially gained traction in the popular press largely through the efforts of several left-leaning journalists, including several at Bloomberg Media, who began promoting MMT advocates like Kelton in their online and television platforms. Other media outlets, including the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, initially ignored the claims Kelton and the like were making but more recently have begun describing calls for increased deficit spending as an "MMT approach." Yet many non-MMT economists, like Blanchard, argue that there's room for similar spending increases while still believing there exists a limit to how much deficit spending a government can engage in without triggering perilous levels of inflation.

If MMT is ever to be understood and defended, or exposed and refuted — if, in other words, it is to be meaningfully engaged at all — we need to be clearer about what MMT is and what it is not. MMT comprises two central claims — that there need be no upper bound on government debt, and that money can be printed without any inflationary consequence. Increased deficit spending alone is not necessarily "an MMT approach" or some sort of validation that "MMT is right," per today's parlance. Rather, it can easily fit under the frameworks of either Keynesianism, whose adherents endorse deficit-financed government spending during recessions, or even supply-side economics, whose supporters on the right endorse deficit-financed tax cuts. Along with neoclassical economics — which argues that, barring default or inflation, all government debt must eventually be paid back in the same amount of future taxes accounting for interest — each of these approaches recognizes that there is an upper bound on government borrowing. MMT, to put it bluntly, does not.

Indeed, what makes MMT unique is that it's the only school of thought (should it be even considered as such) to combine calls for not only increased, but unlimited deficit spending with the argument that central banks can print money to pay off these debts without prompting inflation. There is simply no truth to this assertion. In fact, the reality is much the opposite: As interest costs consume increasing portions of revenue, at a certain point, the government cannot afford to borrow any longer. If the government resorts to printing money to pay its debts, inflation will ultimately follow.

In searching for radical theories to advocate radical policies, MMT apologists have inadvertently come to endorse an approach to economic theory that not only flies in the face of decades of economic research and historical precedent, but would be devastating if ever tested. By tempting progressive politicians into endorsing "dangerous" and "obviously indefensible" economic theories, MMT advocates are setting the stage for potentially disastrous policymaking.

For the very reason that MMT advocates completely gloss over Milton Friedman's famous adage that "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon," MMT could very well be one of the most dangerous economic ideas of our time. As long as academics, entrepreneurs, politicians, and media figures continue to indulge or promote it, those who know better need to shed light on its shortcomings.

Once those in academia and the media begin to speak honestly about what MMT is instead of what they wish it was — when they cease conflating the theory with the policies its advocates also happen to endorse — MMT will be revealed as a grossly inadequate foundation for public policy. Policymakers can then turn their attention to the practical tradeoffs involved in balancing current needs, the imperative to invest in the future, and the undeniable costs of debt. There is no easy way to manage that balance, and pretending otherwise won't help anyone.