The States in Crisis

Over the past three years, the news out of state capitals has been dire. From Albany to Sacramento, economic shocks have reduced states' tax revenues, even as the downturn has required states to spend more on welfare for the struggling and newly jobless. The Great Recession has thus torn gaping holes in state budgets — holes that governors and state legislatures are now desperately trying to close.

That effort has been painful for state officials. When Arizona cut state funding for kindergartens, educators and parents cried foul. When New York raised tuition at its state universities, students protested. When California, North Carolina, Oregon, and Connecticut raised their income taxes, angry taxpayers flocked to Tea Party protests and expressed their displeasure through buzzing phone lines and clogged inboxes. With every attempt to fix state budgets, an acceptable solution has seemed ever more out of reach.

But alarming as these recent developments have been, the states' fiscal calamity is not simply a function of the recession. Their shaky financial foundations were in fact set long ago — through unsustainable obligations like retirement benefits for public employees, excessive borrowing, and deferred maintenance of public buildings and infrastructure. The result has been a long-building budget imbalance now estimated in the trillions of dollars.

The nightmare that governors and state legislators are living through will therefore not end when the effects of the recession do. Even as state officials address large short-term operating deficits, they must confront the more troublesome structural gaps between current state revenue projections and massive future liabilities. And the tools that these state officials have at their disposal to deal with the crisis are limited. Many state constitutions require the repayment of bonds to take priority over almost all other state spending. Others require state-employee pensions to be paid out at the promised terms no matter what, making it almost impossible to negotiate those liabilities down. States, unlike municipalities, do not have the legal option of declaring bankruptcy. At some point, if some states approach default, just meeting these debt obligations will consume all of their revenues — leaving no money for basic functions like maintaining a state police force, operating roads and other transit infrastructure, or educating children.

If these states fail to find their way out of their current predicament, their only option may be to beg for federal bailouts. And the states would not be the only losers if this comes to pass. If the federal government were to refuse a bailout request, it would risk a disastrous crisis in the bond markets — as investors who had always assumed state debt to be safe (in part because they assumed it would have federal backing in a crisis) would suddenly rethink all their state-bond investments. On the other hand, if the federal government were to grant a bailout to any one state, the other 49 would certainly expect assistance as well. This would put our federalist system to an unprecedented test. It would also require an enormous amount of money from federal coffers that are themselves perilously hollow.

It is in everyone's interest, at all levels of government, to avoid such a collapse. Gratifying as it may be to scream about the various Armageddon scenarios facing the states, it is far more useful to consider how those problems might be solved through our everyday political and policy processes — precisely to avoid truly extreme measures. Policymakers can start by getting a better handle on the problem: Just how big is the crisis? What caused it? And if America's elected leaders and voters are serious about reform, what exactly should they do to pull the states back from the brink?

THE FISCAL CRISIS

The first step in getting a better handle on the crisis is to understand why the Great Recession has been so brutal to state budgets. The main reason is that the recent lean years were preceded by several fat ones, in which state politicians oversaw massive increases in state spending. Following a pattern reaching back decades, policymakers chose to use times of relative prosperity and growth to irresponsibly expand the size and scope of government services. When tax revenues declined precipitously as a result of the 2008 financial crisis, state officials' optimistic budgeting crashed into cold, hard reality.

As a result, the scale of the fiscal challenge facing most state governments today is immense. State tax revenues were 8.4% lower in 2009 than in 2008, and a further 3.1% lower in 2010. The demand for many state services, meanwhile, has increased as a result of the economic downturn. Medicaid enrollment (and with it state spending on the program) grew by more than 13% between the end of 2007 and the end of 2009. As unemployment spiked, unemployment insurance and welfare payments ballooned. The states thus faced a combined budget shortfall of nearly $200 billion — or almost 30% of their combined total budgets — in 2010. Most expect shortfalls nearly as great in the next fiscal year.

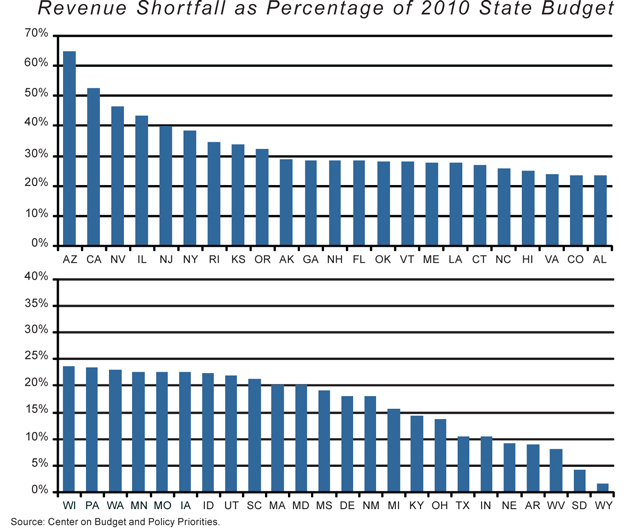

Beyond its startling magnitude, the crisis is also widespread. A few states with oil or mineral wealth (Alaska, Montana, and New Mexico in particular) weathered the recession relatively well at first, though even they have not avoided budget shortfalls. Most everywhere else, the combination of declining tax revenues and rising unemployment has produced a painful budget squeeze. The two charts that follow show each state's revenue shortfall as a percentage of its budget (the first chart lists the worst-performing states, and the second the best-performing states).

With the exception of Vermont, every state is required by its laws or constitution to balance its budget (though many of these requirements are quite flexible in their definitions of "balance," as discussed below). State governments have thus been unable to carry huge deficits from one year to the next, and have been forced to find ways to immediately close their immense budget gaps.

Many states have found relief in the form of substantial federal aid: The 2009 stimulus bill provided about $140 billion to the states over three fiscal years, largely through increased Medicaid dollars and a "State Fiscal Stabilization Fund," which states have used to fill other gaps. The "jobs bill" enacted in August 2010 gave the states another injection of Medicaid dollars, and added another $10 billion to the stabilization fund. Of course, federal assistance of this magnitude will probably not be available in the coming years. For now, however, these federal dollars have helped fill about 35% of the total combined deficit in state budgets.

Yet even that aid has left states far short — so most have also had to take serious steps to curb spending or raise revenues. In fact, since 2008, 46 states have cut services to residents: According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 31 states have cut health-care funding, 29 have cut services to the elderly and disabled, 34 have cut K-12 education funding, and 43 have cut higher-education funding. More than 30 states, meanwhile, have increased taxes in the past three years — 13 states have raised personal income taxes; 17 have raised sales taxes; 22 have increased taxes on tobacco, alcohol, or gasoline; and 17 have increased business taxes. Most individual changes in tax rates have been modest, but their combined effects have been significant, adding up to almost $30 billion in 2009 (almost 4% of total state revenues).

As grim as these indicators are, they do not even capture the whole picture — for it is impossible to study the finances of state governments across the country without taking into account the finances of local governments as well. In most states, the two levels of government are legally and practically interrelated: Counties and municipalities are not independent constituents of federations, the way the states relate to the federal government; rather, they are creations of states, designed to carry out state functions.

Moreover, the division of labor among the levels of government differs from state to state. In some places, public-school teachers are classified as state employees; their salaries and benefits are therefore funded primarily by state income or sales taxes, and show up on the state's books. In other states, teachers are classified as district employees — and their expenses are paid from local property or sales taxes. Similar differences exist in other budgeting categories, such as law enforcement, social services, and transportation. As a result, the most accurate method of examining state finances — and the cleanest way to compare them across state lines — is to combine state and local expenditures.

When we do, what does the spending picture look like? According to the most recent official data from the Census Bureau, for the 2008 fiscal year, states and localities spent about $2.8 trillion. (The spending was funded through revenue from state and local taxes and fees, as well as through federal grants, loans, and trust funds.) Of that amount, some $2.4 trillion was classified as "direct general expenditure" — the major programs and services that attract most of the attention of state policymakers and citizens. About a quarter of these "direct general expenditures" went to public K-12 schools; higher education, public safety, and transportation each claimed about 10% of the total. Public-assistance programs — including Medicaid, cash welfare, and housing subsidies funded mostly by Washington — made up about 30%. The remaining 15% or so funded smaller programs such as parks, the management of natural resources, or business recruitment, as well as general administration. As a share of the national economy, such state and local spending has roughly doubled over the past 50 years — from 11.56% of GDP in 1959 to 21.79% today.

In assessing this incredible growth, it is essential to take into account the influence federal spending has over state spending. Indeed, since much of the revenue that makes state spending possible comes from federal transfers, it is impossible to disentangle the two. For example, the biggest jump in state and local spending occurred in the decade after President Lyndon Johnson implemented his Great Society programs: From 1965 to 1975, state and local spending went from 12% to nearly 17% of GDP. By far the most important cause of that spending explosion was the creation of Medicaid, which combines federal and state dollars to provide a package of acute and long-term health care for the poor and disabled. This structure offers perverse incentives for policymakers to constantly expand the program: State and local officials benefit from providing ever more generous benefits without having to shoulder a proportional share of the financial cost, since the federal government pays most of the bill. Likewise, any effort to contain costs by cutting benefits harms state and local officials immensely, and in exchange, most of the savings go to the federal government. Consequently, ever since Medicaid was created, it has been one of the largest and most relentless drivers of state budget growth.

Another major driver is education, the largest single category of state and local spending. Both K-12 and higher-education spending have grown during the past two decades — by 10% and 3%, respectively, as a share of GDP — as states have raised teacher pay and benefits, hired more teachers to reduce class sizes, built more expensive facilities, and added large numbers of administrators and support staff. In most jurisdictions, per-pupil spending in elementary and secondary schools now approaches or exceeds $10,000 (for comparison, the average annual tuition charged by private schools across all grade levels, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Education Statistics, is $8,549). In the case of higher education, some governors and legislatures have recently begun to reduce the subsidies provided to public universities; there are still many states, however, where most of the cost of a public undergraduate education is funded by taxpayers, not the student's tuition.

Other familiar state and local services, such as transportation and law enforcement, have actually experienced little real growth in spending over the past two decades. For example, despite increases in the federal and state taxes on motor fuels — revenues that fund much of the nation's spending on roads and bridges — increases in the average fuel efficiency of the cars traversing America's highways have pushed actual revenue collections per mile traveled down. The result? Less money to maintain, repair, and expand our primary system of surface transportation — which means more roads that are crumbling and congested.

This funding shortage for America's roads may seem surprising, given the astronomical amounts of government money spent on transportation. The reason is that a large — and egregiously wasteful — chunk of state and local transportation budgets is devoted to obsolete transit and rail programs, which seek to apply the leading technologies of 1900 to the mobility needs of 2011. Because much of the money for these projects ultimately comes from the federal government — in the form of highway bills and other pork-laden legislation — the funding dynamic that governs transportation is similar to the one that obtains with Medicaid. The fact that only a fraction of the money comes from locally raised taxes gives state and local politicians significant incentive to pursue transportation projects that would make no sense in the absence of federal largesse. But in order to get the federal money for transit projects, state and local authorities must invest some of their own revenues — often in significant amounts. So the lure of federal money for rail programs often ratchets up state and local transit spending.

A recent example of this phenomenon is the situation surrounding New Jersey governor Chris Christie's decision to cancel a rail-tunnel project that would have provided an additional link between the Garden State and New York City. Much of the opposition to the governor's decision stemmed from the argument that New Jersey would lose out on federal backing — the federal government and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey were to provide $3 billion each for the project, and the state of New Jersey was on the hook for $2.7 billion, plus any cost overruns. It was when those overruns were projected to be between $1 billion and $5 billion that Christie pulled the plug, arguing that the burden was too much for the state to bear.

When all of this wasteful spending is combined with the recent budget shortfalls caused by the recession, the states face a total projected deficit of $130 billion in the coming fiscal year. But unfortunately, this is only the beginning: Most observers do not expect to see state revenue collections return to pre-recession levels until 2014, at the earliest. And even when the recession does pass, the massive long-term budget imbalances will still be there — poised to bring in a new, and far more difficult, set of fiscal challenges. The bill for decades of reckless promising and spending is about to come due.

UNFUNDED LIABILITIES

High on the list of reckless expenditures and promises are unfunded government pensions. When Wall Street tumbled in 2008, it drove down the values of many state retirement funds — leaving policymakers with far less time than they thought they had to bridge huge gaps between saved resources and promised benefits. But state and local lawmakers were not simply the victims of bad timing and bad luck — they were the perpetrators of bad planning and bad policy.

At the heart of this problem lies the fact that government pension plans do not function the way most private retirement plans do. Americans with jobs in the private sector are likely most familiar with "defined contribution" retirement programs — like 401(k) accounts — which involve a set contribution (generally some percentage of one's pay). This contribution, made over the course of a person's working years, is channeled into a savings account that accrues interest; upon retirement, that account begins to pay out benefits. An individual can generally choose how to invest the money in his account to improve its rate of return; he can also buy an annuity when he retires to insure against an old age that outlasts the account's reserves. Such a retirement plan cannot be underfunded, since it pays out in benefits only what one contributes over the course of one's working life.

Most government pension plans, by contrast, are "defined benefit" programs. These plans, as the name suggests, guarantee a particular annual benefit to each retiree (generally based on the income he earned while he was working, the number of years he worked, and some cost-of-living adjustment). Instead of disbursing payments based on the amount of money collected over time in a savings account, defined-benefit programs work backwards: They first determine the benefits they will provide, and then try to calculate how to collect enough money to meet those obligations. The accuracy of that calculation depends on correctly predicting the rate of return that the retirement funds will be able to draw over the years — which makes defined-benefit programs extremely vulnerable to fluctuations in the stock market (and the economy more generally).

The structure of defined-benefit programs also strips away the safeguards that protect defined-contribution programs from being underfunded. If a defined-benefit plan promises excessively generous payouts, or fails to collect enough money to meet its financial pledges to retirees, the result will be a massive accumulation of debt as large numbers of workers begin to retire. Of course, many states have done both. Forty-eight states (Alaska and Michigan are the only exceptions), as well as a great many local governments, provide defined-benefit retirement plans to their employees. And even before the recent financial crisis caused the stock market to tumble, many of these plans were seriously underfunded.

Just how short are these retirement plans? According to a recent report from the Pew Center on the States, state governments face an unfunded liability of $1 trillion for retirement benefits promised to public employees. This figure, which remains the most accurate available assessment of the problem, is based on FY 2008 data — that is, before the financial markets and economy really tanked. More recent estimates, calculated by Northwestern University economist Joshua Rauh and his colleagues, have suggested a figure closer to $3 trillion in unfunded state liabilities (the shortfall in city pensions totaled an additional $574 billion).

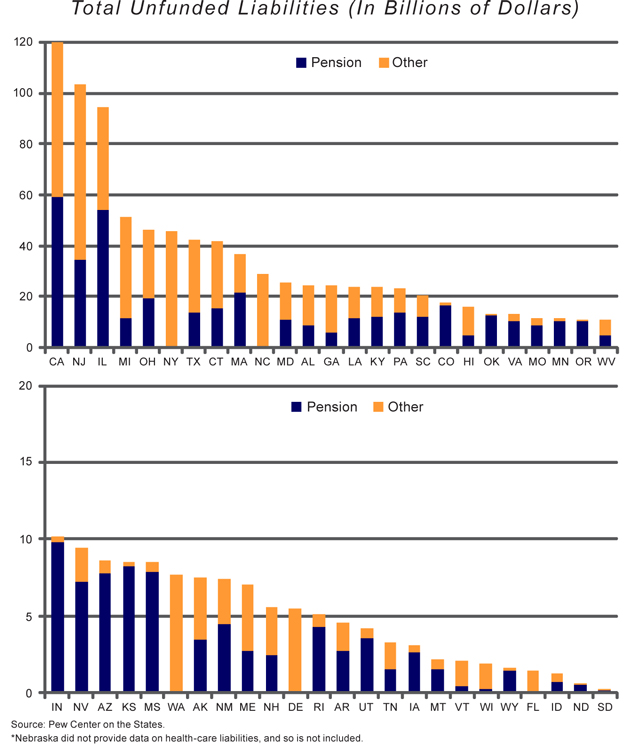

Yet alarming as the recent headlines about underfunded pension funds may be, pensions are not in fact the primary reason that states are facing a meltdown in their retirement funds. Indeed, according to the Pew study, state pension systems as a whole had accrued about 84% of the assets needed to pay projected benefits as of 2008; the long-term pension hole came to about $450 billion. The states' greater challenge is paying out promised benefits other than cash pensions — benefits for which the states have, astonishingly, set aside virtually no money at all. The most problematic of these obligations is of course health care — specifically, the coverage above and beyond Medicare that many state and local governments have promised to their retirees. That unfunded liability came to about $550 billion — which, when combined with the $450 billion pension hole, produced what Pew called the "Trillion Dollar Gap." The charts below break down this sum by state, showing the dollar amounts (in billions) of each state's pension and other (principally health-care) retirement liabilities.

Of course, the populations of the states and the sizes of their budgets vary enormously — which means that the sheer dollar amount of a state's unfunded liability may not always be the best measure of the severity of its fiscal crunch. So while these figures offer a sense of which states would require the most money — either from Washington bailouts or their own tax coffers — to make their underfunded retirement programs whole, they do not necessarily tell us which states have done the worst job of managing their liabilities. It is therefore useful to consider exactly what portion of each state's total retirement liability is unfunded.

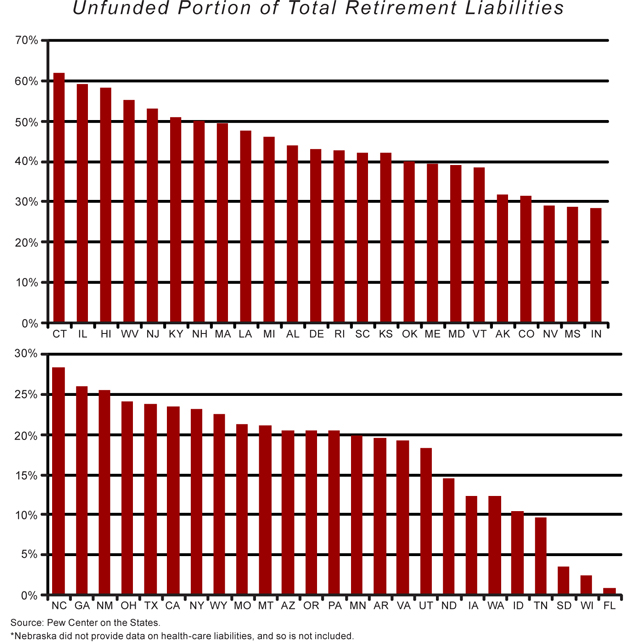

As the following charts demonstrate, there is wide variation in how the states have managed their pension obligations. As of 2008, Connecticut, the worst offender, had no money set aside to pay for a staggering 62% of its total retirement liability. At the other extreme, Florida had a small surplus in its pension system and only modest health-care obligations — making it the best-funded state retirement system in the nation.

By examining the data presented in both of these sets of charts — both the sheer size of a state's unfunded liability, as well as the portion of its total retirement liability for which no money has been saved — one gets a sense of the severity of each state's fiscal troubles. California, for instance, ranks near the middle of the pack in terms of the portion of its retirement obligations that is unfunded. But because of the enormous size of both its population and state work force, the Golden State's total unfunded liability amounts to more than $120 billion — making California's predicament far more grave in real terms than the woes of some states that have failed to fund even larger portions of their projected liabilities. The states that rank near the top of both dishonor rolls — most notably Connecticut (62% of its liability unfunded, for a total unfunded obligation of almost $42 billion), Illinois (59% of its liability unfunded, for a total unfunded obligation of $94 billion), and New Jersey (53% of its liability unfunded, for a total unfunded obligation of $103 billion) — are in the worst trouble of all.

Unfunded liabilities for retirement benefits are both outrageously irresponsible and completely avoidable — and yet wholly unsurprising. To the average governor or state legislator, what matters most is what is happening right now. During economic booms, when revenues are pouring into state coffers, it is politically popular to increase compensation for public employees, hire more teachers to reduce class sizes, expand eligibility for Medicaid and other safety-net programs, or cut taxes. The lobby for setting aside more money in pension and savings accounts, on the other hand, is minuscule. During economic busts, when revenues crash and countercyclical spending soars, it is even more difficult to convince state policymakers to make long-term needs a priority. Forced to choose among cutting personnel (and thereby adding to the jobless rolls), reducing current benefits and services (just when struggling residents are most in need of them), raising taxes (when working families need every bit of their paychecks to make ends meet), or deferring contributions to state savings accounts, the last option — which, in the here and now, seems to have virtually no downsides — is almost irresistible.

This phenomenon is evident not only in the states' management of financial capital, but also in their approach to physical capital. It is far more exciting for politicians to break ground on new buildings and infrastructure than it is to commit state dollars to the maintenance, repair, and renovation of facilities already in use. New construction signifies growth, progress, and expanded access to popular services like education and transportation. Fixing up old facilities is rarely front-page news. Public administrators have thus fallen into the habit of letting facilities problems fester, putting together capital plans that focus on new construction rather than repair or maintenance. The private sector, too, is a party to the scheme: After all, developers, contractors, and tradesmen typically enjoy far higher profit margins from new construction than they receive from maintenance and repair. Members of these professions — and the unions that represent them — simply add pressure in state capitals to build anew rather than maintain the old.

As a result, while the number, size, and market value of state and local buildings and facilities have increased dramatically over the past two decades, budgets for maintenance, repair, and renovation have not kept pace. Many public buildings have thus ceased to become local-government assets, becoming instead additional unfunded liabilities that will consume a great deal of money not currently acknowledged in state budget projections. According to another Pew Center study in 2008, only six states — Florida, Indiana, Nebraska, Texas, Utah, and Vermont — had adequate infrastructure-maintenance policies. Twenty-two states got failing grades for infrastructure, including familiar mismanagement case studies like Illinois and New Jersey.

The combination of vastly unfunded retirement liabilities, poorly maintained physical capital, and general waste and mismanagement has thus left states with budget holes that seem nearly impossible to fill. The states facing the most ominous difficulties, moreover, are in many cases the ones that already have the highest tax burdens — leaving them little room to raise taxes further without driving residents and businesses out of state and thus making matters worse. To propose cuts in spending, jobs, and government services, meanwhile, would be unwise in difficult economic times (and politically painful at any time).

It is therefore not surprising that state policymakers in search of money pursue the path of least resistance: heavy borrowing. But unfortunately for state taxpayers, this borrowing only intensifies the problem — piling enormous and expensive debt onto already wobbly state and local budgets.

THE CURSE OF PUBLIC DEBT

As of fiscal year 2008, states and localities combined had about $2.6 trillion in outstanding bonded obligations and other formal debts. By the beginning of 2010, the Manhattan Institute's Steven Malanga reports, state and local debt had risen to an all-time high of 22% of GDP, up from 15% a decade ago. But the amount of outstanding government debt attributable to state and local spending is far greater still — because a great deal of the money borrowed by the federal government ends up being funneled to the states.

Consider that, since 1967, the federal government has run budget deficits in all but five fiscal years — and that, in the past few years, those federal deficits have been in the neighborhood of a trillion dollars a year. In all of those deficit-spending years, total federal grants to states and localities amounted to at least 40% of the federal deficit; in most years, a majority of federal borrowing went straight to state and local budgets. Over the past decade, the trend grew even more pronounced: In the seven years starting with the return of deficit spending in 2002 (after the brief bipartisan budget-balancing of the late 1990s), virtually all of America's federal deficits were consumed by revenue transfers to states and localities, primarily for Medicaid and education. This trend was reversed in 2009, as Washington responded to the recession with a panoply of federal spending programs, driving deficits to unprecedented heights. About 40% of the deficit in the past two years has gone to states and localities.

The consequences of having Washington as a borrower of last resort have been quite severe. Most state constitutions forbid the practice of financing recurring operating costs through borrowing, and rightly so. Access to easy credit is particularly dangerous for teenagers and politicians, for similar reasons: They lack the long-term incentives, and often the knowledge and self-discipline, to make wise decisions. It's best to impose responsibility on them through budget rules. Unfortunately, easy access to federal borrowing subverts the states' well-intentioned balanced-budget requirements. If state politicians can ask Washington for extra Medicaid money, education funds, or other bailouts to fill in holes during recessionary years, they have fewer incentives to control state spending growth when times are good — or to pare back expenses when a recession hits.

The result is a ratchet effect in state spending; through booms and busts, the inexorable trend is higher spending in real terms. Over the past half-century, federal aid to states and localities has grown from about 1% of GDP in the mid 1960s to 3.6% of GDP in 2010. During the same period, total state and local spending rose from about 12% of GDP to nearly 22%. States and localities would likely have increased their spending even without federal borrowing — but access to its proceeds undoubtedly helped make state and local budgets much larger than they otherwise would have been.

Furthermore, because many federally funded services — such as Medicaid, public education, and highway management — require state matching funds, the result of increasing federal "aid" can be calamitous for state taxpayers in the long run. A recent study by economists Russell Sobel and George Crowley for George Mason University's Mercatus Center found that state taxes rise between 33 cents and 42 cents for every dollar a state receives in federal aid. Federal programs that fund state and local spending "create their own new political constituency," Sobel and Crowley observed, "in that the government employees and private recipients whose incomes depend on the program, and their families, will use political pressure to fight against any discontinuation of the program." The end result, Sobel and Crowley wrote, is that federal grants "result in an expansion in state lobbying activity that is successful in gaining influence over future state spending."

Access to the federal credit card isn't the only counterproductive "gift" Washington extends to states and localities. Another is the distortion of capital markets caused by the federal tax policies surrounding state and local bonds. The interest earned by state and local bondholders is exempt from federal income taxes, which inflates the incentive to buy such bonds — in turn making state and local debt artificially cheap (and therefore exaggerating its appeal to state and local policymakers). Indeed, the exemption for state and local bonds — with a fiscal impact of about $27 billion a year — is one of the largest in the federal tax code, after the mortgage-interest deduction (worth about $89 billion) and the state and local tax deduction (worth about $41 billion).

The main justification for exempting state and local bonds from income taxation is that the federal subsidy helps governments afford important capital projects such as schools and roads. Because the return on the bonds is not taxed, governments can offer lower interest rates to investors and still remain competitive with the private bond market. And since this allows governments to borrow at lower rates of interest, governments theoretically save money that can then be passed along to taxpayers.

But in reality, because government bonds have artificially low interest rates, state and local governments end up borrowing more than they otherwise would in order to finance more infrastructure projects than they would otherwise build. In this sense, governments behave like many prospective home buyers: If mortgage rates go down, thereby allowing a person to buy a bigger house with the same monthly payment, he has certainly gained an advantage — but he has also purchased a bigger house, and can't pretend that he has pocketed a savings. State and local officials already have enough perverse incentives to build themselves bigger houses; they do not need additional enticement to spend every last dime they can get their hands on.

An additional danger of the tax exemption for state and local bond interest is that it can crowd private-sector vendors — and, with them, private-sector cost efficiencies — out of large economic ventures. Again and again in debates about building city-owned convention halls, arenas, ballparks, and corporate centers, the case is made that government, not the private sector, should take the lead — because government can do the job cheaper, as its debt costs less to finance. A similar problem emerges with regard to public-private partnerships. In many instances, it would make fiscal sense for private firms to build, maintain, and lease back to public authorities facilities such as schools and toll roads. But opponents often argue that the potential savings — in the form of speedier construction, more economical designs, and better maintenance — are outweighed by the higher cost of servicing taxable private debt. Worse yet, when politicians do recognize this problem, they end up finding ways to give private firms access to the proceeds of taxpayer-backed debt — a "cure" that is often far worse than the disease. There are private companies whose business models consist wholly of cultivating enough political pull in statehouses or city halls to get a piece of the "economic development" pie — an open invitation to influence-peddling and corruption.

There are many other programs and incentives that have helped create enormous, long-term structural divides between the revenues that states can expect to receive and the money they will have to spend just to make good on current promises. And just as these liabilities took many years to accumulate, they will take many years to resolve. They will also require dramatic reforms, which will not be easy to accomplish, either politically or practically. The cruel facts of budget math, however, leave policymakers with no choice but to try — and soon.

LASTING REFORMS

How, then, should governors and legislators deal with the simultaneous challenges of an immediate fiscal crunch and a long-brewing budget imbalance? As they confront another tough year in 2011, they will be forced to cut their budgets swiftly and significantly. Smart lawmakers, though, will recognize the upside to their situation. Rather than simply enacting indiscriminate, across-the-board cuts — or seeking only the easiest, most immediately achievable savings — they will seize the opportunity to craft budgets that meet their states' long-term policy needs.

Many of these forward-looking budgets will include targeted spending reductions that can accumulate savings over time. These include eliminating optional Medicaid services (like paying for dentures and eyeglasses rather than hospital stays); reducing non-teacher expenditures in public schools (like administration and overhead); consolidating redundant departments and agencies; tightening control of existing contracts with supply vendors and service providers; subjecting more government services to competitive contracting; and selling unproductive or low-priority government assets (such as little-used office buildings, state-owned liquor stores, and some transportation infrastructure) to the private sector.

Other intelligent budget reforms will be designed to save modest amounts of money today, but vastly larger amounts in the future. Of these, the most crucial changes will be to state pension and health-care plans. For older public workers with defined-benefit retirement plans, states need to implement new guidelines that require longer vesting periods, lower cost-of-living adjustments, higher employee-contribution levels, and higher thresholds for disability claims. For younger public employees, states should end the hollow promise of defined retirement benefits — pensions and health care — altogether. Instead, they should pursue (and vigorously promote) the far more sound approach of defined-contribution plans that guarantee annual investments in personally owned, fully portable accounts.

The most important changes, though, will be structural reforms to processes of government — reforms that eliminate the perverse incentives that got the states into this mess in the first place, and that privilege the concerns of taxpayers over those of spending lobbies and special interests.

With conservatives poised to exercise more real power in state capitals than they have in generations, now is the time to enact fundamental changes in the rules that govern budgeting and legislation. As they do, lawmakers should keep five broad principles in mind.

First, not all balanced-budget requirements are created equal. While nearly all states have some balanced-budget rules, usually coded into their constitutions, the specifics differ widely (as do the resulting constraints on government growth). In 43 states, for example, the governor must submit a balanced budget to the legislature; in 40 states, the legislature must pass a balanced budget. In some cases, though, the definition of "balanced" is so nebulous that a state can, in effect, fund its operations with debt. Some states' requirements, for instance, apply only to their general funds — meaning that the operating costs for "special funds" and off-budget accounts can be paid for with deficit spending. In 21 states, if unforeseen revenue shortfalls or spending spikes create general-fund holes during the fiscal year, the state can borrow to carry over the deficits into the next year.

Research shows that these differences matter, and that states prohibiting carry-overs mount much stronger and more immediate responses to budget deficits — either through budget cuts or tax hikes — than do states with weaker balanced-budget rules. James Poterba of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has found that, for every $100 in deficits that arise in a given fiscal year, states with strong anti-deficit rules (rules requiring that the legislature enact a balanced budget and prohibiting the carrying forward of deficits from year to year) reduce state spending by $44. States with weak rules (which require only that governors submit a balanced budget, or allow deficits to be carried forward) cut their budgets by only $17. Moreover, two papers from the late 1990s (one by Alberto Alesina and Tamim Bayoumi, and another by Henning Bohn and Robert Inman) showed that states with strong anti-deficit rules tend to maintain larger financial reserves — suggesting that they are less susceptible to the boom-and-bust fluctuations of our economy.

Second, states should go beyond balanced-budget requirements and impose limits on overall spending. Today, some 30 states have caps on the annual growth of state budgets; Colorado's Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR) is perhaps the best known. Among the rest, the specifics vary widely and make an enormous difference in effectiveness — highlighting how important it is for states to design their spending caps wisely. Indeed, there is scant evidence that states that set loose limits — by, for instance, limiting budget growth to the rate of growth in personal income, while exempting major categories of spending like education and Medicaid — reap any benefits at all. But states that enforce tight limits (Colorado is again the foremost example) tend to perform better: Those that peg budget growth to changes in inflation and population, allow very few exceptions, and crack down on evasive accounting gimmicks succeed in both controlling government growth and mitigating economic booms and busts.

Third, if politicians are given additional revenue, they are sure to spend it. Spending caps therefore work much better if they are coupled with meaningful tax limits. The TABOR amendment in Colorado, for instance, stipulated that any tax increase that would raise government revenue beyond the inflation-plus-population cap had to be approved by voters in a referendum. Fifteen other states require supermajority votes in their legislatures to approve tax hikes. Those with the strictest caps, like Arizona and South Dakota, also have per capita spending levels well below the national average.

A more basic way to limit state taxation is to restrict the kinds of taxes the government may impose. While most states employ all three major options — property, sales, and income taxes — some states use only two. (Every state has property taxes, seven have no income tax, and five have no sales tax.) Not surprisingly, the states that use only two kinds of taxes have lower levels of taxation overall. It is crucial, then, for policymakers in these states to protect against the imposition of new taxes. For instance, in states that rely mostly on sales taxes — like Florida, which has no income tax, and Tennessee, which taxes income only from dividends and interest — lawmakers must oppose efforts to introduce an income tax. In states that rely mostly on income taxes — like Oregon, which has no sales tax but the highest income-tax rates in the nation — policymakers need to hold the line against the introduction of a sales tax.

There have also been concerted efforts in state capitals to authorize additional revenue sources and to broaden the bases of existing taxes. These initiatives would, for instance, apply retail sales taxes to cross-border Internet transactions and to major service sectors such as law, finance, advertising, and medical care. (Florida, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Maryland are among the states to have attempted such sales-tax expansions in recent years.) This approach is a shrewd one on the part of policymakers, in that spreading a state's revenue haul across multiple levies makes it harder for voters to grasp the full magnitude of their total tax burden. This, of course, makes it easier to raise taxes over time — meaning that the inevitable result will be greater growth in government. Such taxes must be resisted.

Fourth, debt limits must be strict and enforceable. Naturally, there are proper uses of debt in state and local government — primarily to finance buildings and other infrastructure that will remain in service for many decades. Issuing bonds for these projects admittedly increases their lifetime cost, but it also allows needed projects to come into service sooner — giving state residents immediate benefits like increased mobility or proximity to schools. Plus, it spreads the financial burden over the multiple generations of taxpayers who will receive those benefits.

Still, it is clear that the approach to debt taken by most state and local governments today is well outside the realm of the reasonable. To return to sanity, policymakers should require either a voter referendum or a legislative supermajority to issue bonds of any kind — and there should be a clear enforcement mechanism that ensures taxpayers have standing to sue in court to challenge illegal debt issuances. The current practice of distinguishing between general-obligation debt requiring referenda and special-obligation debt not requiring referenda is too easy to abuse, as governments have demonstrated no qualms about reclassifying general-obligation bonds as, for instance, "revenue bonds" or "tax-increment financing," and so treating them as special-obligation debt. As a result, academic research generally finds no consistent relationship between referendum requirements and overall government indebtedness; it does, however, provide clear evidence that referendum requirements increase the issuance of special-obligation bonds. A 2009 study by K.C. Tydgat of the University of North Carolina found convincing evidence of such patterns of evasion by state governments — confirming similar findings in the 1990s by scholars Beverly Bunch and Jurgen von Hagen. Only by imposing constraints on all debt issuance, then, can the problem be tackled.

Fifth, state line-item vetoes can work, but only if they provide governors with the power to reduce as well as eliminate spending items. Governors have the power to strike line items from the budget in all but six of the states (Indiana, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Vermont are the exceptions), and while this power has been shown to reduce spending on occasion — especially when the governor is of a different party than the majority of the state legislature — its overall effect on state spending has not been great. But in states that give their governors the power to also reduce the amount of money spent on a particular line item without simply striking it — Alaska, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin — the use of this power by governors has significantly more effect. As studies by W. Marc Crain, James Miller, and former Congressional Budget Office director Douglas Holtz-Eakin have shown, these effects are, again, more prominent when state government is divided between the parties. But when this is the case, the so-called "item-reduction veto" can significantly reduce spending. In a 2003 book, Crain found that such a power can lower per capita spending by state government by 13%.

People familiar with the history of federal budgeting know how difficult it is to sustain responsible fiscal policy unless the executive branch has meaningful authority over the budgeting process. Logrolling, pork-barrel considerations, and the dynamics of interest-group politics affect all elected officials, but legislators are particularly vulnerable. The same rules apply at the state level: When governors are armed with the most powerful form of the veto — the authority to reduce spending in every line item of the budget, and to gut legislators' earmarks and pet projects — the result is less growth in budgets and taxes.

IMAGINING THE UNAIMAGINABLE

One way or another, 2011 will be a year of reckoning for the states, and for American federalism. As budget gaps persist and pension promises and other obligations come due, several states may confront the possibility of genuine default — a possibility that California briefly toyed with in 2009, and may well face again soon.

If they are to have any hope of avoiding the twin nightmares of default and a federal bailout, governors and legislators must get serious about changing their ways. Guided by the principles outlined above, they need to employ all of their creativity and foresight to avert fiscal collapse, correct budget imbalances, and improve the quality and efficiency of government services.

Even more important, state and local politicians will have to summon uncharacteristic levels of courage and backbone. The policy decisions that this moment calls for — from painful budget cuts to difficult structural reforms — have always seemed politically unachievable. But crises have an odd way of motivating people. And politicians concerned about political fallout should take comfort from the fact that voters, too, are deeply worried. When it comes to rescuing the states, doing what was once politically impossible is quickly becoming absolutely necessary.