The Real Dangers of Marijuana

The revolution in the legal status of marijuana has been rapid and dramatic. Four decades ago, there was a universal prohibition against buying, selling, using, and possessing marijuana. Then, several local and state jurisdictions began to adopt a range of more lenient policies toward marijuana users — eventually including decriminalization and de facto legalization in some jurisdictions.

Three decades ago, large-scale production for profit was banned essentially everywhere. But that, too, began to change. In the 1990s, several states introduced "medical marijuana" programs. Though marijuana use was made legal only for medical purposes, the regulations were often so loose that essentially anyone could get a physician's "recommendation," authorizing that person to purchase marijuana. Suppliers were euphemistically called "caregivers" (even though some never met the "patients" they were caring for), and they sold out of brick-and-mortar retail stores known as "dispensaries." At one point, there were thousands of dispensaries in California alone.

The medical ruse was superseded only in 2012, when voters in Colorado and Washington state passed propositions allowing large-scale commercial production for non-medical use, and the Obama administration announced an official policy of non-interference (within broad limits), despite the fact that all such activity violates the federal Controlled Substances Act. In 2014, Alaska and Oregon joined Colorado and Washington, and several more states are expected to legalize marijuana within the next year.

The change has been amazingly swift, in large part because of the effectiveness of the core argument of the pro-legalization lobby. Advocates of legalization observe that the majority of people who have used marijuana have not been harmed by it in any meaningful way, that intoxication does not produce violence, and that (in contrast to heroin, prescription opioids, and even alcohol) lethal overdose is almost unknown.

Opponents of legalization have (less successfully) countered that responsible scientific reviews in the United States and abroad conclude that marijuana smoke contains known carcinogens; prolonged marijuana use is causally associated with pulmonary problems, dependence, and some mental health problems; and it is correlated in disconcerting ways with a wide variety of other behavioral, mental, and physical health outcomes.

All these statements are true, but they also miss the point. The essential problem with marijuana is neither death from overdose nor organ failure from chronic use. Marijuana might better be described as a performance-degrading drug and, more dangerously, as a temptation commodity with habituating tendencies.

The drug's misleading reputation for harmlessness is based largely on two defining patterns of marijuana use. First, most people who try marijuana never use much of it; perhaps only about one-third of those who try it go on to use it even 100 times in their lifetimes, the common threshold for determining whether someone has ever been a cigarette smoker. Trying marijuana is not dangerous, but using it is. Those who use marijuana on an ongoing basis face a much higher likelihood of becoming dependent than lifetime smokers do of developing lung cancer. Marijuana dependence is neither fatal nor as debilitating as alcoholism, but it is real, harmful, and far more common than is generally acknowledged.

Second, marijuana use is highly concentrated among the growing minority who use daily or near-daily. Adults who use fewer than ten times per month and who suffer no problems with substance abuse or dependence account for less than 5% of consumption. More than half of marijuana is consumed by someone who is under the influence more than half of all their waking hours. Most marijuana users are healthy; most marijuana use is not.

In the resulting confusion, advocates of legalization often argue (effectively) that "marijuana is safer than alcohol." It would be far more accurate to say "Marijuana is safer than alcohol, but it is also more likely to harm its users."

Seeing the matter this way can help policymakers think more clearly about legalization. It is not likely to arrest the progress of the legalization lobby — more and more jurisdictions will probably legalize marijuana in the coming years, and a nationwide legalization could well follow. But there is more to this matter than just contemplating legalization or preparing for it; it is essential that policymakers, public-health officials, and the larger public get beyond the lobbyists' talking points and gain a clear sense of the harms of marijuana.

USE, ABUSE, AND DEPENDENCE

The best data concerning the scope and effects marijuana use come from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH is a very large and well-run survey with about 70,000 respondents annually (roughly 70 times larger than the average opinion poll). Perhaps surprisingly, many people freely admit to using marijuana. Indeed, so many do that customary concerns about out-of-sample populations, while pertinent when estimating rare behaviors like heroin or other injection-drug use, are not a major concern.

Under-reporting by people who are within the survey's sample, by contrast, remains an issue. To convert survey data into estimates of total use, one should fudge upwards by some factor to correct for under-reporting, often guessed to be in the range of 20% to 40%. But our focus here will be on proportions of avowed users who report various problems with their use, not estimating the total number of users. The custom is to define "current" users as those who report consumption within the last 30 days. The surveys estimate that 20 million Americans admit to past-month use. Another 13 million report use within the last year, but not the past month.

The surveys ask about problems users believe they have experienced because of their use. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration consolidates the answers to estimate how many would meet the clinical criteria for dependence (2.8 million) or abuse (an additional 1.4 million) set down by the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (commonly referred to as the DSM-IV). SAMHSA makes these calculations for all substances in an effort to estimate the nationwide need for treatment for each substance.

Since 4.2 million people are estimated to meet the criteria for marijuana abuse or dependence, there is one such person for every 4.8 current users. Or, expressing the ratio the other way around, 21% of current users meet diagnostic criteria.

The NSDUH surveys ask parallel questions concerning alcohol, and the criteria for assessing dependence are almost identical. Marijuana dependence is defined as reporting three or more of six problems; for alcohol it is three or more of seven problems (the six used for marijuana, plus withdrawal). So in a sense it is easier to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence because there is one more category of problems that can contribute to meeting the threshold. Abuse is likewise defined as reporting certain problems, but not enough to be classified as being dependent. (These formulae have recently been updated by the fifth edition of the DSM, but the household survey still uses the fourth edition's criteria.)

It turns out that 137 million people self-report current alcohol use, and 17.3 million describe enough problems to meet the criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, equivalent to one instance of alcohol abuse or dependence per 7.9 current users, or 13% of current users — significantly lower than the corresponding ratio for marijuana.

In all likelihood, both the 21% for marijuana and the 13% for alcohol understate the true extent of the problem, because denial is a hallmark of addiction. But if the rate of under-reporting problems among those who do admit to use is comparable for both substances — which is plausible because we're talking about reporting of problems by those who admit use, not the reporting of use in the first place — then the ratio of those ratios (0.21/0.13 = 1.62) may be a fair quantification of how much more common abuse and dependence is with marijuana than with alcohol. Thus, marijuana may generate about 62% more abuse and dependence per current user than alcohol does. If one focuses on just the more serious diagnosis of dependence, a little over 14% of past-month marijuana users meet the criterion for dependence, compared to only a bit under 6% of past-month alcohol users — meaning that marijuana appears to generate not just 62% but 133% more dependence per current user than alcohol.

These findings pertain to population-level use in the United States at this time. They are not statements about individual risks as they do not come from experiments that randomly assign some people to use marijuana and other, otherwise-identical people to use alcohol.

One could speculate that legalization might make marijuana abuse and dependence less common, because generally healthy people will start to use occasionally, and that influx could dilute the proportion who abuse or are dependent. But one could just as easily speculate that legalization will bring more marketing, more potent products (like "dabs"), or products that are more pleasant to use (like "vaping" pens), any of which could increase the risk that experimenting could progress to problematic use. This is all speculation, of course. But what can be said empirically is that, within the context of aggregate use in the United States at this time, the best available data suggest that marijuana creates abuse and dependence at higher rates than does alcohol.

Likewise, in 2012 the Treatment Episode Data Set recorded 681,374 treatment admissions for which the primary substance of abuse was alcohol and 305,560 for which it was marijuana or hashish. That works out to 15 admissions for every 1,000 current marijuana users versus only 5 for every 1,000 alcohol users. Similar results pertain to emergency-room "mentions" recorded by the Drug Abuse Warning Network — with the caveat that "mentions" do not imply the drug caused the emergency-department visit. Fair comparisons are not possible for those over 21 because DAWN does not record alcohol-only episodes for adults, but DAWN counts about the same number of emergency-room mentions involving marijuana (120,584) as alcohol (117,653) among those under the age of 21, even though past-month alcohol use is substantially more common than is past-month marijuana use.

Part of the difference may be that most people who use marijuana do so with the express purpose of getting intoxicated, whereas many people drink occasionally just to quench their thirst or to complement their dinner. Only about 44% of those who report drinking within the last month say they consumed five or more drinks on the same day, so if one limited the alcohol data to only those having five or more drinks in one day, then the problem rates for the two substances would be more similar.

THE REAL RISKS

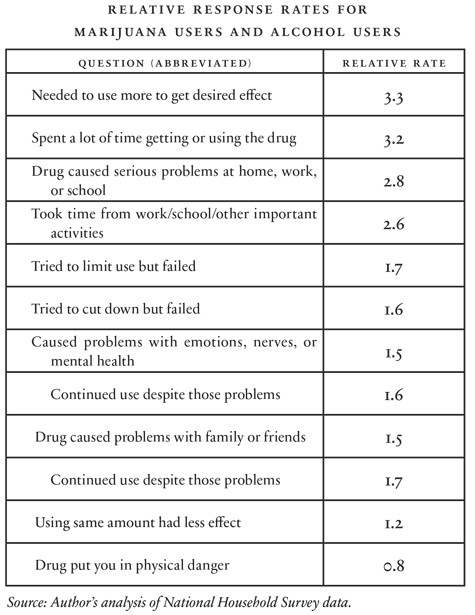

As mentioned above, SAMHSA assesses abuse and dependence based on about 20 questions that ask about particular problems the respondent might attribute to his use of the substance. We can compute ratios of rates for these individual questions the same way we computed the 1.6 ratio for abuse or dependence. For technical reasons, we do this with the data from 2012 and not 2013, but the basic findings have been stable year after year since the current batch of questions was first implemented in 2000. Indeed, one finds the same basic results in even older surveys in which questions differed in particulars but were similar in spirit. For example, the recent surveys ask the following question, along with a completely parallel question for marijuana:

Sometimes people who drink alcohol have serious problems at home, work or school — such as: neglecting their children, missing work or school, doing a poor job at work or school, losing a job or dropping out of school. During the past 12 months, did drinking alcohol cause you to have serious problems like this either at home, work, or school?

More people reported that alcohol caused such problems (3.9 million) than marijuana did (1.5 million), but since there are seven times more alcohol users, the relative rate was 2.8 times higher for marijuana than for alcohol. The table below reports the relative rates for questions to which at least 5% answered "yes" for either substance.

The differences across questions suggest a pattern. Marijuana appears most problematic relative to alcohol with respect to questions about life functioning — including the one mentioned above concerning serious problems at home, work, or school. Marijuana also appears to create problems with self-control at a greater rate than alcohol does, though the margin was smaller. Alcohol was scored as more dangerous on the question "did you regularly drink alcohol and then do something where being drunk might have put you in physical danger?" versus its marijuana analog.

Given these data, it is hard to imagine how marijuana's reputation for harmlessness has persisted for so long. Two related observations can help explain that persistence, however: Most people who try marijuana do not use it much, and most usage is highly concentrated among a small proportion of users. It is worth taking a closer look at these patterns.

First, most people who try marijuana do not suffer adverse consequences for the simple reason that they do not use it much. For example, up until 1998, the surveys asked about the number of times respondents had used in their entire lives. Of those admitting any use, 45% reported consuming on fewer than 12 occasions in total; only about one-third reported using on more than 100 occasions. By comparison, tobacco researchers often don't count someone as ever having smoked unless they have used on at least 100 occasions. If marijuana researchers followed that example, statistics concerning the likelihood of progressing to dependence would sound very different.

This point is so important it is worth diving into specific numbers. The best available evidence, albeit dated, suggests that something like 9% (or, according to another set of data, 15%) of people who try marijuana will become dependent on it at some point in their lives. In particular, James Anthony and colleagues found that, among all respondents surveyed by the National Comorbidity Study in 1990-92, 46.3% reported ever trying cannabis even once, and 4.2% reported having experienced enough problems with their use at some point to merit a diagnosis of dependence. From these numbers, they calculated that "only 9.1% of the users had developed cannabis dependence." Their corresponding proportion among 15- to 24-year-olds was higher, at 15.3%. Even though dependence takes time to develop, the overall rate was lower — 9.1% versus 15.3% — because back in 1990-92 most people over age 35 or 40 never had the chance to try marijuana when they were young and therefore more vulnerable to losing control of their habit. Since most people who try marijuana today do so as teens, the 15.3% might be the more relevant statistic going forward.

Regardless of whether one favors the 9% or the 15% figure, it is crucial to recognize that almost no one whose lifetime exposures total to fewer than 100 occasions of use becomes dependent. So the dependence rates among those who do go on to use on more than 100 occasions are three times as high: 27% or 45%, not just 9% or 15%. In short, merely trying marijuana isn't very dangerous, but using it on an ongoing basis can be risky.

Second, marijuana use is highly concentrated among the small proportion who use daily or near-daily (defined conservatively as reporting use on 21 or more days in the past month, which excludes the lump of people who report using on 20 days). Only one in five past-year marijuana users report consuming that often. However, because they use the drug so frequently and because they consume a lot when they do use, they consume most of the marijuana consumed in America.

The best data pertain to days of use. These most-frequent users, though they represent just 20% of all users, account for two-thirds of all the days of use that are reported. Data on grams consumed per day are sketchier, but it appears that daily and near-daily users consume about two or three times as much per day as do occasional users, which would imply that they account for roughly 80% of the quantity consumed.

This concentration of consumption means that the typical session of marijuana use involves someone who is not the typical user. Adults who are in full control of their occasional use probably do not suffer many adverse consequences. However, adults — meaning people age 21 and over — who have no substance abuse or dependence issues with marijuana or any other substance and who use fewer than 10 times per month report less than 5% of all use days recorded by the survey; their share of marijuana consumption is probably less than 3% because they tend to consume smaller amounts when they do use.

Those who report using every single day, on the other hand, account for 45% of the reported days of use and more than 50% of the weight consumed. Since daily users are thought to consume (on average) the equivalent of three to four joints per day, it seems literally true that the average gram of marijuana is consumed by someone who is under the influence of marijuana more than half of all their waking hours.

So even though the average person who tries marijuana does not become a regular user, the average episode of use involves a daily user. And even though most people who use marijuana do not suffer problems, that does not mean marijuana is harmless. Most pack-a-day smokers don't get lung cancer; indeed, only about 5% to 20% do, depending on when they start and if they stop. That proportion is only modestly greater than the risk that merely trying marijuana will lead to dependence, and is less than half the risk of becoming dependent if one has used enough marijuana to meet a tobacco-style definition (at least 100 occasions) of ever having been a marijuana user.

REDEFINING HARMLESSNESS

One of the most effective arguments of the legalization lobby is that marijuana is safer than alcohol. Indeed this idea has, to a large extent, set the terms of the debate over legalization. It is true that people using marijuana rarely take the physical risks that those using alcohol are sometimes inspired to take. And alcohol undoubtedly kills more people than marijuana does, and at a higher rate per user, not just in total.

A common estimate of all-cause alcohol-related mortality is 88,000 premature deaths per year in the United States. That is sometimes contrasted with there being effectively no known lethal dose for marijuana. (Unlike heroin, which could kill even a healthy person in a high enough dose, marijuana's safety ratio is so high that it cannot be effectively measured.) Almost no one using exclusively marijuana has died by single-drug acute overdose.

But that hardly means marijuana is safe. While alcohol is more dangerous in terms of acute overdose risk, and also in terms of promoting violence and chronic organ failure, marijuana — at least as now used in the United States — creates higher rates of behavioral problems, including dependence, among all its users.

Furthermore, even if it were possible to ascertain that alcohol is more dangerous than marijuana or vice versa, that fact would be of no particular relevance. Very few people systematically research the pros and cons of various dependence-inducing intoxicants and then decide to consume just one. Most people who use marijuana also drink alcohol, and the two are often used together. The surveys ask what other substances were consumed the last time the respondent drank. Among current marijuana users, 44% report using marijuana with alcohol the last time they drank, a proportion that rises to 67% among daily and near-daily marijuana users.

The real trouble is not that marijuana is more or less dangerous than alcohol; the problem is that they are altogether different, and the comparison is simply unhelpful in informing the debate over marijuana policy. The country is not considering whether to switch the legal statuses of alcohol and marijuana. Unfortunately, our society does not get to choose either to have alcohol's dangers or to have marijuana's dangers. Rather, it gets to have alcohol's dangers — modulated perhaps by higher or lower drinking ages and higher or lower taxes — and also marijuana's dangers — modulated by how legalization or prohibition affect prices, product variety, marketing, and usage.

Instead of comparing the harms of marijuana when it is prohibited to the harms of alcohol when it is legal, an intellectually honest marijuana-policy analysis ought to compare all possible harms under marijuana prohibition to all possible harms under legalization. And that analysis ought also to worry about indirect effects on abuse of other illicit drugs, alcohol, and tobacco — outcomes for which the current evidence is scant, divided, and discouraging, respectively.

THE RIGHT APPROACH

Unfortunately, there is very little in the way of intellectually honest marijuana-policy analysis. The loudest voices have been those of the billionaires George Soros and the late Peter Lewis, channeled through their organizations, the Drug Policy Alliance and the Marijuana Policy Project, respectively. Those individuals and organizations are committed to the proposition that marijuana should be legalized, and they marshal data and rhetoric that support their position — that's how most advocacy organizations work. Increasingly the industry itself is being heard, too, through its trade association (the National Cannabis Industry Association) and lobbyists.

There are opponents to legalization. With the exception of the Drug Enforcement Administration, most opposition comes not from government but from non-profit groups like National Families in Action, Smart Approaches to Marijuana, the Institute for Behavioral Health, and the Hudson Institute.[correction appended] The governmental heavyweight, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, is quick to point out marijuana's dangers but even quicker to disavow having any official position on policy questions like legalization or decriminalization.

My colleagues and I in the academy have sought to inform public discussion of legalization by adjudicating the competing claims advanced by either side. Here, however, instead of dealing with the question of whether marijuana should be legalized, it may be a more fruitful exercise simply to view legalization as an important event, the likelihood of which makes planning for it prudent. (Among my colleagues, the consensus is that, at present, the odds seem better than even that within 15 or 20 years the federal government and most U.S. states will have legalized marijuana production and sale, even if some states remain "dry.")

A key point we try to explain — most recently in an extensive analysis done with colleagues at RAND for the State of Vermont — is that legalization is not a binary choice. There are many different "architectures" for who gets to supply marijuana legally and myriad "design choices," such as what the tax rates will be and whether sales will be limited to stand-alone stores or extended to grocery and convenience stores as with cigarettes. So it is appropriate to ask not just whether but also how marijuana should be legalized, and not just in the technical, wonkish sense but more holistically.

Marijuana has four defining characteristics that make dealing with it difficult from a policy standpoint. First, it is a performance degrader. Advancing pharmacology may well challenge society in the not-too-distant future with the issue of what to do with cognitive enhancers — an Adderall that actually works — but marijuana is not such a substance.

Second, it is dependence-inducing. Marijuana is not crack, but marijuana dependence is nonetheless a real and not-uncommon consequence of prolonged use. This challenges the usual free-market presumption that consumers reliably maximize their welfare, particularly given that the vast majority of users start using before they are adults.

Third, marijuana is, for the most part, not directly harmful to third parties. While impaired driving and workplace use are concerns, and 1 million children live with a parent or guardian who meets diagnostic criteria for marijuana abuse and dependence, most of marijuana's direct harms fall on its users, and the families and friends who care about them.

And fourth, its health harms are, for the most part, minor. Yes, marijuana smoke contains carcinogens, and, despite vehement denials by legalization proponents, the evidence suggests that marijuana can trigger mental-health problems, including psychotic episodes. But the scale of those harms per unit of use does not distinguish it from other permitted recreations, including skiing and sky diving.

A substance with all four of these attributes presents a policy challenge in a free society. The usual presumption that the government should not interfere with companies' efforts to cater to consumers' whims is challenged by the reality that so much marijuana is consumed by people with diagnosable substance-use disorders. These characteristics in combination violate the axioms classical economics uses to conclude that the unfettered free market will maximize social welfare.

It is clear we would all be better off if marijuana did not exist. Given the abundance of alternative sources of intoxication and fun, the harm suffered by abusers probably outweighs the pleasure derived by its controlled users. On the other hand, the paucity of third-party harms or "externalities" undermines the standard justification for government intervention. A modern secular state does not arbitrarily declare some items to be forbidden and others to be halal or kosher. We are accustomed to mandates that protect against immediate, tangible physical-health harms, such as seat-belt laws, but many bridle against taxes on sodas or other social engineering designed to fight obesity or promote exercise. And the threats marijuana does pose are obstacles to nebulous objectives like "achieving one's potential" and bourgeois totems like academic and career success, not concrete harms like heart disease.

So the question remains: How should a freedom-loving, market-oriented society respond to a dependence-inducing substance that degrades performance but doesn't much damage bodies or cause harm to third parties? Some policy scholars have offered approaches that may point the way toward reasonable policies.

In 2003, Thomas Babor and several colleagues wrote Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity, which captured the idea that, even though alcohol is a commercial commodity, public policy should not default to treating it the way we treat avocados and anchovy pizzas. Alcohol is important and distinctive enough to craft a special set of rules particular to it.

With regard to drugs and other activities (gambling, for instance) that are not dangerous enough to merit banning outright, Mark Kleiman has argued for "grudging toleration." That means allowing adults access to some legally produced supply, hopefully on liberal enough terms to undermine the black market, but with restraints and hoops for users and suppliers to jump through that will be seen as features of the regulatory regime, not wrinkles to be ironed out. For example, Kleiman suggests that even adults should be required to pass a test to earn the right to use, the way one must earn the right to drive, rather than conferring that right universally upon reaching a certain age. And such licenses could be used to enforce limits on amounts purchased per week or per month.

Marijuana is likewise no ordinary commodity but a temptation good that society should tolerate grudgingly. There are many ways of putting that philosophy into practice. One way is to start by restricting production and distribution to non-profits or for-benefit corporations whose charters mandate that they merely meet existing demand, not pursue unfettered market growth to maximize shareholders' returns and owners' wealth. It would also be wise to require these organizations' boards to be dominated by public-health and child-welfare advocates. Furthermore, regulatory authority should be put in the hands of agencies like the FDA whose loyalties are to the public welfare, not industry, and who maintain a healthy suspicion toward industry motives and practices.

The particulars of such an effort, however, are not important at this stage. Most important is the principle: to grant only grudging toleration because marijuana is no ordinary commodity.

Unfortunately, the prevailing sentiment in the legalization debates couldn't be further from this cautious stance. The legalization movement has celebrated its victories as though they were triumphs for civil rights. Regardless of whether legalization is good or bad policy, it is certainly not a cause for jubilation. Borrowing again from Mark Kleiman, choosing legalization over prohibition or vice versa just trades one set of problems for another. Choosing prohibition means choosing black markets; choosing legalization means choosing greater drug dependence. It is trite but true: A country can choose what kind of drug problem it wants, but it cannot choose not to have a drug problem.

We are in the process of choosing the problem of greater drug dependence and smaller black markets. While it makes sense to appreciate the benefits of eliminating black markets and their attendant harm, sober minds ought to be honest about the tradeoffs and deeply — perhaps even urgently — engaged in how to minimize the downsides of this choice. Even if legalization is a net win, it needs to be seen as the lesser of two evils, and informal social controls need to be developed to replace the formal legal controls that are being removed.

By being honest about the risks and costs of marijuana use, sensible policymakers can ensure that future legalization, if it must occur, is managed in the safest, most responsible possible way.

Correction appended: The text originally misstated the name of the non-profit organization Smart Approaches to Marijuana. We regret the error. [Return to text]