Subsidized Housing and Upward Mobility

In 1983, Harvard scholars Mary Jo Bane and David Ellwood sought to determine the length of time participants in Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) spent in the program. Their report, titled The Dynamics of Dependence, revealed that the average participant could be expected to remain in AFDC for 10 years — a figure that increased to 11.6 years when accounting for multiple spells. These findings helped shape the debate that culminated in the 1996 welfare-reform law, which sought to decrease long-term dependency by imposing a five-year lifetime limit on welfare receipts.

Government housing programs have largely escaped the kind of policy reevaluation that reshaped cash welfare in the 1990s, even as they have grown to surpass cash welfare in scale and scope. Today, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program (which replaced AFDC) and the Supplemental Security Income program serve 2.8 million and 7.4 million beneficiaries, respectively. As of 2024, housing subsidies go to over 9 million beneficiaries.

Recently, however, data made available to the American Enterprise Institute through a research request filed with the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has enabled us to estimate the likely duration of a spell in public and government-subsidized housing for both new entrants and the existing tenant population. To do so, we took advantage of a key feature of housing programs: To remain eligible, tenants must apply annually for recertification. This requirement allowed us to observe households regularly over the course of their tenure.

Our analysis, covering roughly 4.5 million households, found that a majority of tenant spells in public and government-subsidized housing extend beyond the 10-year average spells of welfare receipts identified by Bane and Ellwood. Moreover, this occurs in many households whose head is not in the workforce or seeking work, despite being neither elderly nor disabled.

Allowing such long spells for individuals who might otherwise find employment discourages their upward mobility and keeps other needy households on waiting lists. Establishing time limits for tenants with the capacity to work could help allocate scarce housing resources more effectively while encouraging greater self-sufficiency.

THE STATE OF SUBSIDIZED HOUSING

Today, the federal government provides housing through three broad types of programs: public housing, which is owned by local housing authorities; privately owned subsidized housing, often called "project-based assistance"; and the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, commonly known as "Section 8." Project-based assistance is linked to the unit rather than the tenant. HCV, which is linked to tenants who choose their own units, provides vouchers to low-income households that cover a portion of their rent in privately owned housing facilities. Additional subsidies include income-restricted apartments built through the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program and programs administered through the Department of Agriculture.

Many major income-support programs set ongoing conditions for eligibility. This is not true of subsidized-housing programs. Once a household qualifies for a public or subsidized unit based on income, the only continuing requirement the program imposes on the head of household is that he annually recertify his continued income-based eligibility. The subsidy amount may fluctuate, but a household that remains within income limits for its family size is assured continued support with few additional conditions.

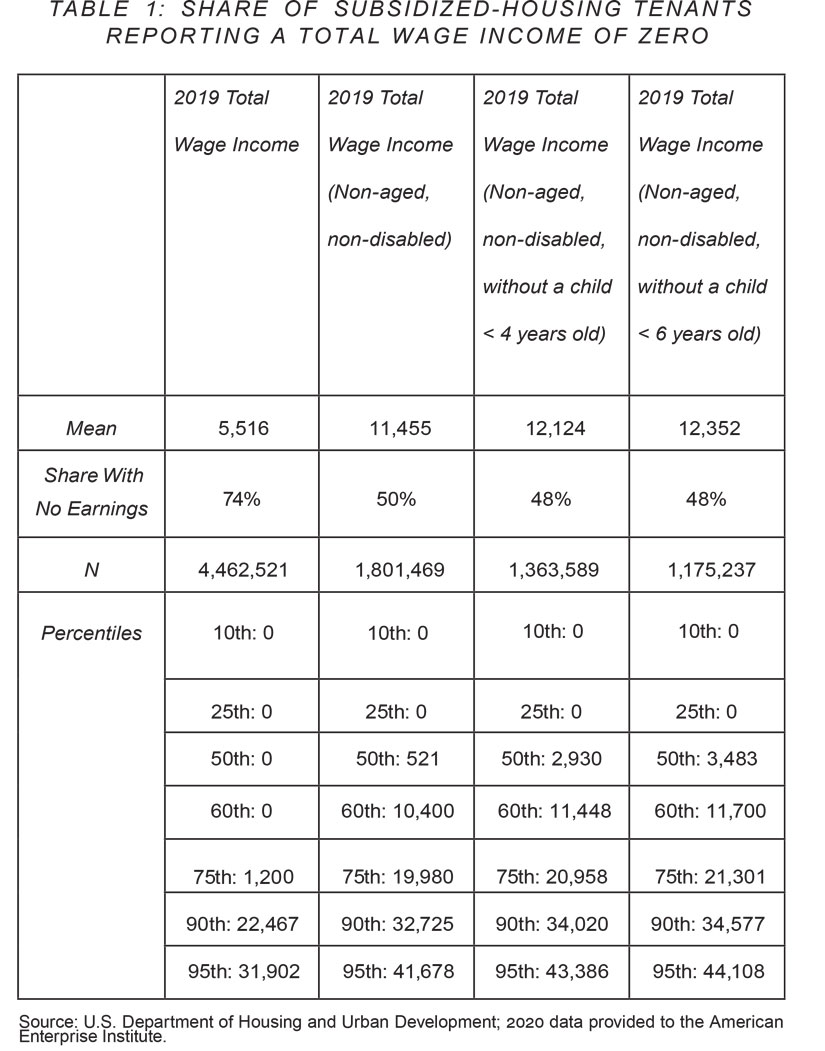

Generally speaking, federal housing programs do not require the head of the household to be employed or seeking work. This diverges from programs like TANF and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which require employment, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which imposes work requirements on able-bodied adults without children. Even Medicaid, thanks to recent legislation, imposes such requirements in some circumstances. Housing programs do not. In fact, as Table 1 indicates, 74% of households in subsidized housing report no income from wages. This statistic includes a significant group — almost half — of non-elderly, non-disabled household heads, who would likely be able to find work but do not do so.

The National Housing Act, as amended in 1969, only contributes to the problem: It limits tenants' rent payments to 30% of their adjusted monthly income. The rule was enacted in the name of tenant protection, but in practice, it operates as a disincentive for those who would seek to increase their earnings. As their income rises, the share of rent tenants must pay increases in tandem, by virtue of an effective 30% marginal tax rate. This 30% often adds to the implicit tax rates that low-income individuals face as SNAP, Affordable Care Act subsidies, and other benefits phase out, further discouraging work.

The non-contingency of housing subsidies extends to their duration: There is no time limit on how long a tenant can occupy a subsidized unit. Participating households often remain in subsidized housing for many years, even a lifetime. Though housing assistance is not the only safety-net program without a time limit — Medicaid and the EITC also lack fixed duration caps — it differs from other programs in a fundamental way: Housing assistance is not an entitlement. In other words, eligibility for public and subsidized housing does not guarantee access. Rather, accessibility is constrained by the supply of housing units.

Today, there are under 1 million public-housing units in the United States. The number of HCV vouchers (currently over 2.3 million) is determined annually through the federal-budget process. Due to the limited supply of units, many households remain on waiting lists for years, with no clear path to assistance. Successful households wait an average of 20 months to enter public housing and 26 months to receive a voucher. The lack of time limits on housing stays thus affects not only tenants, but also those who qualify for assistance but don't receive it.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has long claimed that only one in four households eligible for vouchers receive any form of federal housing assistance. Since local public-housing authorities administer waiting lists, HUD does not report national or local figures for how many households are standing in line. But in many cases, growing demand has prompted the outright closure of waiting lists, further obscuring our picture of unmet need.

Even the lucky few who obtain housing vouchers after a multi-year wait often have difficulty finding a place to use their vouchers. This problem has recently been highlighted by researchers at New York University, who find that only about 60% of voucher recipients are able to obtain a lease. In this context, making the best possible use of limited housing subsidies becomes not just important, but urgent.

HOUSING SPELLS

Just how long do tenants spend in subsidized housing?

HUD data have long shown the average period that housing-program tenants have spent in a unit since their move-in date: 11.8 years for those on public-housing assistance, 10.3 years for those using vouchers. While these data provide valuable insight, they capture only the length of ongoing spells — that is, how long current tenants have lived in their units. They do not reveal the full length of completed spells, or how long we can expect current tenants to remain in their units. Such information would give us a more complete picture of our federal housing programs.

Determining the total length of government-provided and government-subsidized housing spells is a complicated task. This is largely thanks to a bias that plagues publicly available data on in-progress spells. Looking at just a single year of data limits us to observing a snapshot of ongoing spells, many of which are incomplete. This means we miss how long those spells will ultimately last, leading our sample to underrepresent the duration of completed spells.

To avoid either understating or overstating the length of housing spells, we adapted a method proposed by Stephen Salant in the appendix to his 1977 article "Search Theory and Duration Data," which estimated spells of unemployment. His approach hinged on the assumption that the underlying process generating unemployment spells has remained stable over time. Statisticians and economists call this presumption "stationarity."

In the housing context, stationarity assumes that tenants entering the program over the observed period are doing so under roughly the same conditions as those who entered earlier, and that the probability of exiting a housing program at any given time has remained constant. Building on these assumptions, we can invert a formal expression from Salant's appendix to estimate the distribution of completed spells for new entrants using a single snapshot of in-progress spells, thereby correcting for the fact that many of these observed spells are incomplete.

Additionally, to better understand the experiences of current occupants of public or subsidized units, we apply a transformation of the distribution described above that accounts for the fact that these individuals are disproportionately in the midst of longer spells. This allows us to compare the likely trajectory, albeit modeled, of the current subsidized-tenant population.

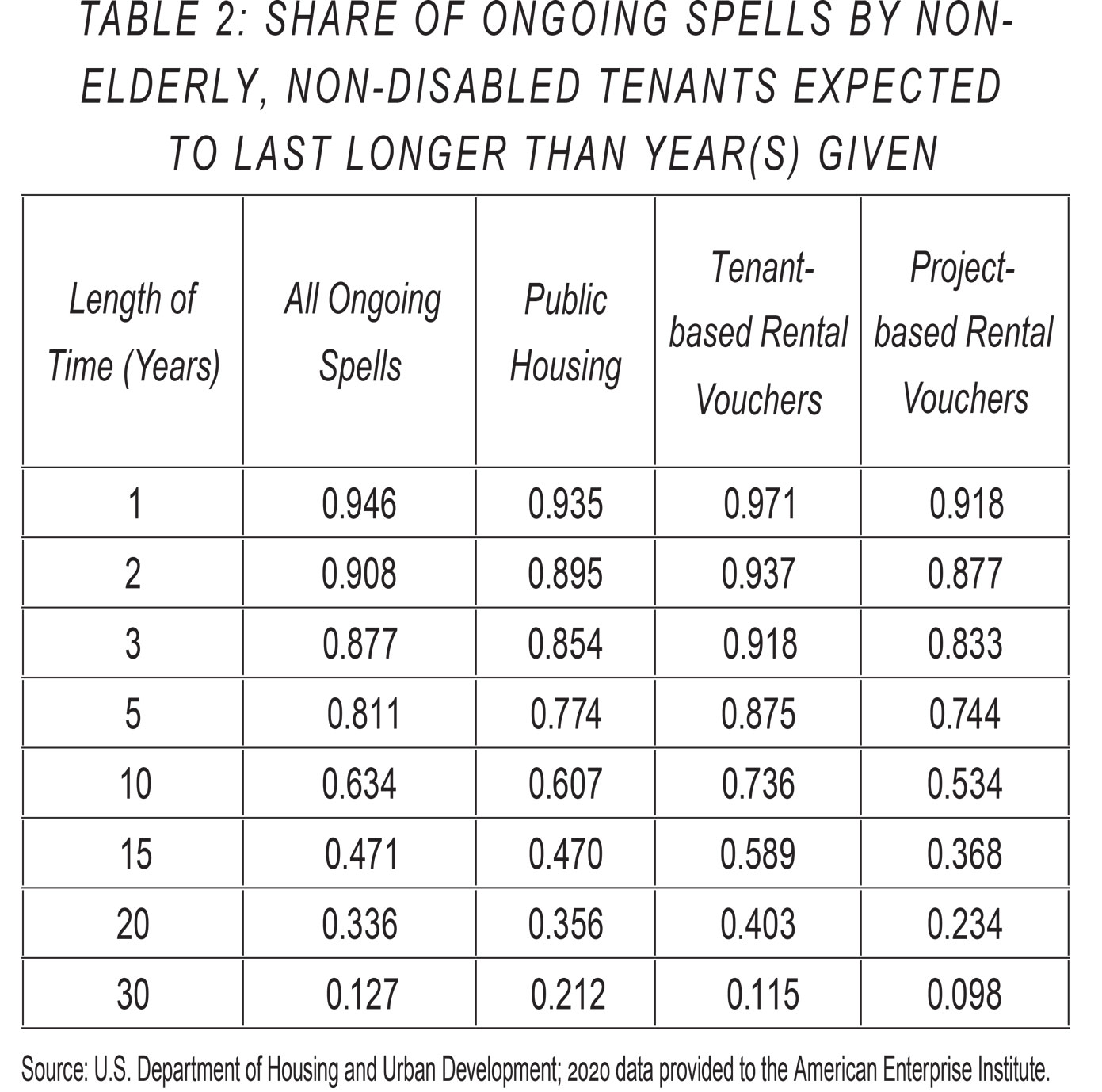

Our results appear in Table 2 below. We have segmented the results by program type: Public Housing, Tenant-based Rental Vouchers, and Project-based Rental Vouchers. We also separately estimate the spell distribution for non-elderly, non-disabled household heads, a sub-group for whom labor-force involvement and eventual transition to market housing are more plausible. Our analysis is based on data recorded in 2020.

These results tell us that, although on average, current non-elderly, non-disabled tenants have lived in their units for around 10 years already, such numbers can hide the extent to which a substantial share of such households have very short or very long stays, and do not reveal the length of completed spells in government or subsidized housing. Those spells — like the spells for cash welfare before its reform — can only be described as lengthy, with 81% of non-elderly, non-disabled participants spending more than five years as program tenants and 63% more than 10 years. The sheer length of these spells, combined with the fact that many similar households are not receiving aid, suggests a need for reform.

PURSUING MOBILITY

Our findings indicate a clear conclusion: Instead of encouraging employment and self-sufficiency, current open-ended housing programs often lead to long-term tenancies. This accords with Brian Jacob and Jens Ludwig's research comparing the outcomes of winners and losers in a large, oversubscribed lottery for public housing in Chicago: They found that lottery winners had lower employment and earnings, as well as greater use of other government benefits, than those who didn't move into subsidized housing. Their work shows that being a subsidized-housing tenant causally reduces work effort and increases welfare-benefit use.

The most straightforward way of addressing the problem would be to impose a ceiling on the length of time households can spend in public or subsidized housing. A time limit would signal to tenants that they should build their savings in anticipation of exiting a housing program, thereby spurring them to seek employment or alternative housing arrangements. Encouraging turnover would also make better use of the existing stock of public and subsidized housing, allowing additional eligible households to take advantage of the programs available.

Public- and subsidized-housing duration caps are not unprecedented. In 1996, the Clinton administration adopted a program that permits a small number of public-housing authorities — currently 39, in a system of more than 3,000 — to engage in policy experiments, including imposing time limits on new tenancies. The housing authority of San Bernardino, California, has set such a limit; tenants agree to it in exchange for the opportunity to maintain a fixed rent. The program recognizes hardship exemptions, such as "unforeseen and involuntary loss of income," as well as "near-elderly" status and the need to complete education or job training. However, no time-limit exception can exceed two years.

This experiment has shown promising results. San Bernardino authorities have found that their tenants tend to move up and out of public housing before the five-year limit. Earned income for families in the program also rose by an average of 31% during their five-year term of assistance, while full-time employment increased by 20% and unemployment decreased by 27%.

As noted above, the San Bernardino model keeps a tenant's rent share fixed at the entry level. This feature removes the 30% marginal rate on rent payments that discourages tenants from seeking more lucrative employment, or any employment at all. Such a policy might be complemented by tenant escrow accounts, into which would be deposited the rent-payment increases that the household would have incurred under the 30% rule. This money could accrue interest, and perhaps even be coupled with future tax-free withdrawals. The flat-rent reform would also offset the current de facto marriage penalty, whereby a single adult who marries is penalized by a higher rent because the additional wage-earner increases the household's income.

Of course, a flat-rent policy puts a lot of emphasis, as well as an implicit tax, on a recipient's income at the beginning of his tenancy. It also does not insure against any future earnings drops. Yet, as economist Thomas Sowell has remarked, "there are no solutions. There are only trade-offs." Policymakers would do well to take note of the tradeoffs associated with a flat-rent policy and attempt to mitigate their downsides when crafting and negotiating potential reforms.

A final beneficial reform would be to give tenants the ability to earn money through subletting, a time-honored practice among low-income households. Seventeen percent of subsidized tenants — typically tenants whose children have grown up and left home — are currently categorized as "over-housed," meaning their units have empty bedrooms. It seems reasonable to allow these tenants to sublet these rooms.

These reform suggestions should not be taken as definitive. Policymakers interested in addressing the problems outlined will need to further examine how they affect their constituents. They must take care to ensure that their proposed reforms don't create perverse incentives or needlessly harm low-income families.

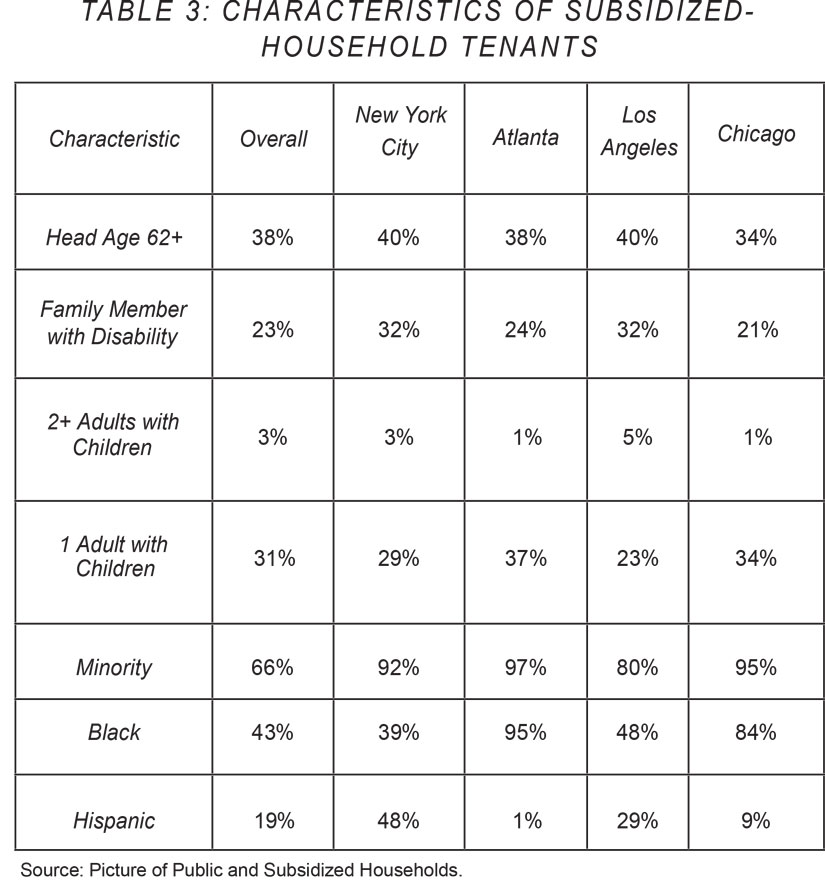

Policymakers should also keep in mind how proposed reforms might affect certain demographics. The racial aspects of these reforms, to take one example, are complicated. Black Americans constitute 43% of all public- and subsidized-housing tenants nationally, as can be seen in Table 3 — much larger than their population share. In some cities, the black share is even higher — 84% in Chicago and 95% in Atlanta.

What's more, housing waiting lists are also skewed toward racial minorities. These groups are disproportionately hurt by a program that provides large benefits to a small share of those eligible while also discouraging mobility. They would therefore be disproportionately helped by one that was more equitable and promoted self-sufficiency.

Finally, policymakers should keep in mind that many people receiving housing assistance are elderly or disabled. As of 2024, 23% of household heads have lived in public housing for more than 40 years. In the nation's largest public-housing system — that of New York City — the average period spent in a housing project exceeds 20 years. This is not a group that should face an immediate time limit. To guard against such outcomes in the future, however, time limits would be appropriate for new, non-elderly, non-disabled tenants, for whom authorities might designate a percentage of units.

As with welfare reform, a housing-program time limit could lay the foundation for a cultural change in public and subsidized housing. Rather than being understood as an open-ended entitlement that makes scarce safety-net-style benefits available only to a fortunate subgroup of those eligible, these programs would be reframed as a short-term form of transitional support meant to facilitate upward mobility in the longer term — to incentivize tenants to move "up and out," as it were.

UP AND OUT

Originally conceived during the New Deal and championed by writer Catherine Bauer in her seminal 1934 book Modern Housing, public housing was expected to serve a large percentage of the population, with a focus on working, two-parent households. Bauer and other proponents conceived of government-owned and -managed housing complexes as a sort of public utility. Yet over time, as post-war private-housing construction boomed in expanding suburbs, public housing evolved into a much narrower system serving predominantly single-adult-led households with limited mobility.

The largely unplanned and unexamined growth of public housing and voucher programs stands at odds with the ethos that overhauled the rules related to cash welfare. The language from a summary on the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 prepared for the House Ways and Means Committee is dramatic:

The major goal [of the law] is to reduce the length of welfare spells by attacking dependency while simultaneously preserving the function of welfare as a safety net for families experiencing temporary financial problems. Based on the view that the permanent guarantee of benefits plays a major role in welfare dependency, Congress is fundamentally altering the nature of the AFDC Program by making cash welfare benefits temporary and provisional.

No similar mission has ever been enunciated for subsidized housing, to the potential detriment of the populations such programs are designed to serve. While taking care not to unduly hobble struggling sectors of the tenant population, policymakers should maintain the goal of encouraging employment and upward mobility among those living in public and subsidized housing.

The benefits of the rule changes outlined above would not substitute for, but would rather be complemented by, local and state reforms expanding housing supply. Relaxing exclusionary zoning and overly prescriptive building codes would also aid voucher recipients, who often have trouble finding places to use their vouchers.

Like all reform efforts, this one raises significant questions. With regard to a time limit, for example, one might ask what subsidized households will do following their tenancy. In light of long waiting lists and extensive need, however, we must assume agency on the part of those subsidized — that they will, like welfare recipients, make changes that enable them to either manage in the private market on their own, cooperate with extended family, or relocate to more affordable locales. Potential complications of policy changes will require continued attention and reform, but they should not deter us from pursuing changes that will likely improve the condition of our fellow citizens.