Reviving Competitive Inquiry

David Hume is said to have declared, "truth springs from argument among friends." If he were alive today, he could have made a profitable career in sloganeering for institutions of higher education. In my own survey of over 600 university mottos worldwide, nearly one-quarter include the word "truth" — a crude albeit useful measure that reflects where universities have stood on the matter for the past several hundred years.

Truth is a topic with which Enlightenment thinkers like Hume engaged humbly. Thomas Jefferson frequently made use of the phrase "follow truth," by which he meant pursue it like a pilgrimage, where the journey itself is the point. This was how universities once conceived of truth. Put another way, for universities, competitive inquiry stood as a core virtue in the quest for knowledge.

Today's university is beset by many problems, but perhaps the most fundamental comes in the form of a weakened competition of ideas. Researchers in 2023 found that throughout the past decade, academic freedom has declined in developed countries around the world. Data suggest that competitive inquiry is suffering as a result.

In the United States, this is likely related to the increasing imbalance in the political affiliations of university faculty members and administrators. As political scientist Samuel Abrams documented in the New York Times, progressive faculty at American universities outnumber conservatives 6-to-1. The ratio is 12-to-1 among administrators.

Illiberalism has also grown pervasive on campus. Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff, authors of the 2018 bestseller The Coddling of the American Mind, discuss the evidence of rising illiberalism at American universities. They point to three ideas — that speech is violence and can hurt us, that we should always be guided by our feelings, and that life is a battle between good and evil — that have pervaded the institutions, all of which justify the stifling of academic freedom.

A backlash is underway. Although not measured until recently, public trust in universities has dropped from 57% to 36% in less than a decade. This distrust stems in part from instances that unmask these institutions' intellectual orthodoxy, like the recent turmoil seen on the campuses of Columbia University and the University of California, Los Angeles, in the wake of Hamas's October 7th massacre of Israelis and the ensuing war. Such instances lead political commentators and the public to ridicule faculty and students. Some of the more radical now advocate abandoning universities altogether.

A glance at the history of universities in the West, however, suggests that the above trends are not historical anomalies; they are merely resurfacing once again. In the university's millennium of existence, its mission has shifted between illiberalism and liberalism, each period underpinned by the extent to which competitive inquiry withered or flourished.

Today's solution mustn't be to abandon the university — a course that ignores the benefits of a system of higher education that places Enlightenment ideals at the fore. Instead, we must investigate the reasons why competitive inquiry is disappearing in this century, and consider how we might help it thrive once more.

A SHIFT TO FREER THINKING

The roots of the modern university can be traced to medieval institutions known as studia generalia, which aimed to educate youth from all over Europe. In the century or two after these early schools sprang up (circa 1100), additional institutions received their charters from monarchs and popes. The University of Paris received its charter from King Philip II in 1200; the University of Toulouse from Pope Gregory IX in 1229; and Cambridge and Oxford from King Henry III in 1231.

The charter system complicated the relationships between those universities and their respective monarchical and religious powers. In Oxford's early centuries, the university enjoyed autonomy from both the Crown and the papacy — that is, until professor John Wycliffe translated the Bible into English against the papacy's wishes. Wycliffe eventually left Oxford, and, after his death, the British Parliament signed into law an anti-heresy statute, which punished heretics with burning at the stake. Over a century later, King Henry VIII strong-armed Oxford into supporting his divorce from Catherine of Aragon. His daughter Mary later used the statute to convict three dissenting clergymen of heresy and had them burned to death on the university's grounds.

The University of Paris underwent a similar rhythm. As Gaines Post details in his book The Papacy and the Rise of the Universities, the institution got off to a rocky start in the 13th century. The disorganized educational structure, unruly townsfolk, and deadly riots drove students and professors out. Finally, in 1231, Pope Gregory IX intervened with statutes outlining the method of instruction for students and autonomy for scholars.

Though this resolved some of the chaos, papal intervention did not come without problems. In the 1250s, controversy erupted between the secular and mendicant professors at the university over whether faculty were subject to civil or papal law. The conflict drew in the likes of St. Thomas Aquinas, a member of the university's theology faculty, and for decades led to the ousting of the university's secular masters, who believed the mendicants — who were not subject to civil law — were unfairly endowed with special status.

For better or worse, universities in medieval times were controlled by the religious and monarchical powers of the day. It was not until the Enlightenment that the university witnessed a tectonic shift from this status quo.

The Scottish Enlightenment serves as the most illuminating example of this transition. Historian David Allan notes that "as recently as 1690 the universities were clearly subjected to what can only be described as systematic purges." That year, the Scottish Parliament established commissions to root out professors who dissented from the Glorious Revolution. Then, during the 18th century, notions of natural jurisprudence — marked by curricula on natural law, interdisciplinary research libraries, and acceptance of unorthodox thinking — filtered into Scottish universities, paving the way for philosophers such as Edinburgh's David Hume and Glasgow's Adam Smith to charge forward mid-century.

By the 1740s, the Scottish Enlightenment was in full swing. Gone were the days of orthodox thinking, when heretics were condemned to death on university grounds. According to Allan, the decisive factor in this shift was an embrace of academic freedom within universities. "For what characterized the Scottish intellectual life by mid-century," he observed, "was a growing openness to new ideas and to speculation, even to what contemporaries called 'free thinking'...that would definitely not have been possible...back in the 1690s."

Freedom of this nature would ultimately suffuse Western universities — especially in the United States. American institutions of higher education were children of the Enlightenment. In 1780, several American founders established the American Academy of Arts and Sciences — an academic association whose founding ideals were entwined with Enlightenment thinking. Per its charter, the academy sought to "promote and encourage medical discoveries, mathematical disquisitions, philosophical enquiries...and, in fine, to cultivate every art and science which may tend to advance the interest, honor, dignity, and happiness of a free, independent, and virtuous people." The academy provided a broad forum within which scholars could engage with one another.

Many of America's earliest universities had religious roots. Harvard and Yale were founded by Puritan Congregationalists, and Princeton by Presbyterians — though the scholars within each institution were free, and keen, to debate the principles underlying their beliefs. The University of Pennsylvania and the University of Virginia were among the first institutions to be founded on a modern liberal curriculum rather than that of a religious sect. The University of Pennsylvania did not subscribe to this ideal when it was founded in 1740, but by 1791, it had adopted "a more egalitarian vision than ever imagined before in the colonies, with members of the Board of Trustees from every denomination and the only non-sectarian faculty in the new nation." In 1819, the University of Virginia followed suit. To quote its founder, Thomas Jefferson, the institution was grounded in "the illimitable freedom of the human mind," unbound by orthodoxy.

American universities boomed during the next two centuries. By 1900, nearly a thousand had been established. Approximately 6,000 exist today. In 1870, the first year in which the Census Bureau tracked higher-education degrees, institutions of higher education conferred 9,372 degrees. That number had tripled 30 years later. By 1970, it stood north of a million. These numbers speak not only to the size of the American university system, but the force by which Enlightenment ideals had dispersed throughout the country.

THE PERSUASION REVOLUTION

Underpinning the university's evolution was a shift in emphasis from coercion to persuasion. This emphasis spread beyond the ivory tower, into realms beyond the intellectual. A closer look at the post-Enlightenment bursts of capitalism and democracy helps explain how this took place.

Before the Enlightenment, capitalism as we understand it today did not exist. While markets were present, economic activity was organized around institutions like guilds, which formed to set prices and guard against intrusive competition. At the same time, many religions, including Christianity and Islam, prohibited the practice of lending money at interest. No one assumed that supply-and-demand forces naturally produced a "correct" price of a good or service.

Democracy at the time, while sporadically practiced in the ancient world, was considered a dangerous path to incompetence, mediocrity, and tyranny. Consistent with what Plato had written in the fourth century B.C., democratic systems were thought to create perverse incentives for corrupt men to accumulate power through dishonest argument. Plato himself asserted that the best outcomes for society required rule by leaders with wisdom, expertise, and upstanding moral character. Unlike these "philosopher kings," the common people were thought to have "no true knowledge of reality, and no clear standard of perfection in their mind to which they can turn." Such beliefs supported monarchic and other non-democratic systems for millennia.

In both governance and economics, pre-Enlightenment authority was exercised, and disputes were resolved, via coercion — the use of rules and force. The anti-heresy statute of 1401, the mendicant controversy in Paris, the Scottish commissions amid the Glorious Revolution, and the many executions that took place therein, all speak to this reliance.

The Enlightenment's radical idea was that we could find mutual benefit in persuasion, and then — within reason, at least — let the chips fall where they may. In politics, this meant democratic decision-making, free elections, and diplomacy. In economics, it meant negotiation between buyers and sellers to organize markets and establish prices. In the world of ideas, it meant free speech and expression.

As Enlightenment philosophers championed persuasion over coercion, Europe and North America witnessed a flowering of both democracy and capitalism. Within government, authority was now thought to require consent, which hinged on persuasion: "The liberty of man, in society," wrote John Locke in 1689, "is to be under no other legislative power, but that established, by consent, in the commonwealth." Within the marketplace, negotiation of the lowest market price — again relying on persuasion — set up a virtuous cycle between creditors and borrowers, who were each incentivized to lend responsibly and repay faithfully.

Developments in democracy and capitalism brought with them an unparalleled devotion to free speech and expression. In the second half of the 20th century, universities in the democratic-capitalist West were bastions of new ideas, which were experimental and often subversive of those in power. The free-speech movement of the 1960s was launched at a government-funded university (the University of California, Berkeley) — an unthinkable phenomenon in centuries past, as well as outside the West. No such movement existed at Moscow State University; protesters there would likely have met the same fate in the Soviet Union in 1968 as that of any foolhardy Oxford students marching against Henry VIII in 1540 (who would have probably been among the estimated 72,000 Britons executed under his reign).

Within universities that championed Enlightenment thinking, all kinds of ideas — including those that might have been considered countercultural, subversive, and offensive — were tolerated, and even celebrated. In hindsight, such a shift seems extraordinary. In less than three centuries, heresy transformed from a capital offense to a cherished right. As Robert Ingersoll, the famous American free thinker of the 19th century, wrote in his 1874 book Heretics and Heresies: "Heresy cannot be burned, nor imprisoned, nor starved....It is the eternal horizon of progress."

Ingersoll provided another bit of wisdom, which was less a defense of heresy and more a warning to those who abandon it: "Heresy is a cradle; orthodoxy, a coffin."

THE RISE OF ORTHODOXY

It was the university that fostered the Enlightenment thinking that toppled coercive power structures in the West. And it is the university today that has spawned a new orthodoxy, complete with a renewed endorsement of coercion.

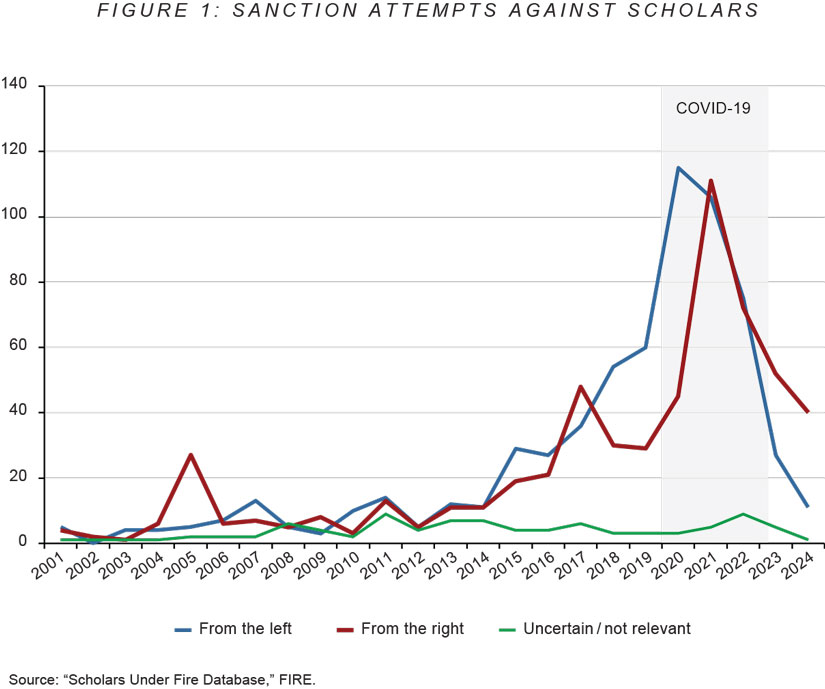

Intellectual orthodoxy on campus marked by a left-leaning bias has become increasingly stifling in the 21st century. The most compelling data come from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), a non-partisan organization dedicated to sustaining free thought in America. In a 2023 report, FIRE tracked the number of attempts to professionally sanction scholars for speech that, in public settings, would be protected under the First Amendment.

As Figure 1 below shows, sanction attempts have risen dramatically in the last two decades. In 2001, only 10 such attempts occurred; by 2021, that figure had jumped to more than 200. During that time, 65% of attempts resulted in successful sanction. Twenty percent resulted in termination.

Those pushing these efforts typically exhibited a left-wing bias. Sanction attempts from within a university — that is, by undergraduates or scholars — tended to come from those with views to the left of the scholar being condemned. Among undergraduate-led sanctions in the years studied, 75% came from the left; among scholar-led sanctions, 82% came from the left. And while progressives appear to have initiated these trends, the report notes that right-wing groups, such as Turning Point USA, began retaliating in 2021 by attempting to sanction 61 scholars perceived to be left wing.

An important fact to remember is that American scholars have never been granted full license to engage in the purest form of Ingersoll's heresy. In 1940, the American Association of University Professors spelled out prudential limits on academic freedom: "[Scholars] should remember that the public may judge their profession and their institution by their utterances. Hence they should at all times be accurate, should exercise appropriate restraint, [and] should show respect for the opinions of others." Academic freedom is not, and never has been, synonymous with speech protected under the First Amendment. Still, skyrocketing sanction rates demonstrate that the Overton window on campus has narrowed, and that "respect for the opinions of others" is no longer a high-order concern.

Formal sanctioning is not the only marker of the new intellectual orthodoxy. Each year, FIRE releases a report on the best and worst universities regarding their speech climate. According to FIRE's 2024 report, the characteristics that distinguished universities in the top five and bottom five slots were their scores on "Tolerance Difference" and "Disruptive Conduct." Students from schools in the bottom five (which included Harvard, Georgetown, and the University of Pennsylvania) tolerated controversial progressive speakers but also supported "disruptive and violent" protest to stop conservatives from speaking on campus. Alarmingly, de-platforming attempts from the bottom five universities had an 81% success rate.

What explains the shift from freewheeling heresy to a smothering form of orthodoxy?

Myths have long existed about academia's left-leaning bias, but evidence from the 1970s through the 1990s shows that it was not especially high. Self-identified liberals made up less than half of the academy during the latter half of the 20th century. Today, as we have covered, the liberal-to-conservative ratio has swelled to roughly 6-to-1.

Historian Phillip Magness points to one reason behind the shift: Academic disciplines that skew left have grown disproportionately. In the last 20 years, the biggest gains in faculty shares have occurred in the arts, humanities, and social sciences — disciplines that tend to veer left. Meanwhile, the biggest losses have occurred in the natural sciences and engineering, which tend to lean right. The result, argues Magness, is a "skewed growth pattern [that] has increased [a left-leaning] footprint on campus relative to other faculty, and it has done so at a time of an additional leftward shift in their own ranks." "The cumulative effect," he adds, "is to pull the university system as a whole even further to the left."

A deeper problem is also afoot — namely the university's shift in emphasis from competitive inquiry to activism, which has exacerbated the left-leaning trends noted above. Since 2016, America and the world have endured lightning-rod political events: the election of Donald Trump, the Me Too movement, the murder of George Floyd, the coronavirus pandemic, Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and, most recently, Hamas's massacre of Israelis on October 7th. Many higher-education institutions took public positions on the most polarizing issues of the day. These periods of activism correlate with the highest number of attempts to sanction scholars and de-platform speakers.

Activism by institutions was once eyed with suspicion. In 1967, the University of Chicago released the Kalven Report, a document that outlined the university's role in "political and social action." America in the 1960s was fraught with sociopolitical strife as the civil-rights movement gained steam and the situation in Vietnam deteriorated. Yet amid the turmoil, the Kalven Report recommended institutional neutrality. "A university," the report argued, "if it is to be true to its faith in intellectual inquiry, must embrace, be hospitable to, and encourage the widest diversity of views within its own community." In language that will seem almost foreign today, the report continued:

There is no mechanism by which [a university] can reach a collective position without inhibiting that full freedom of dissent on which it thrives. It cannot insist that all of its members favor a given view of social policy; if it takes collective action, therefore, it does so at the price of censuring any minority who do not agree with the view adopted.

As the authors of the report recognized, institutional activism threatens academic freedom and, in turn, competitive inquiry. It decimates social trust and transforms reasonable disagreement into hatred. It creates in-group and out-group dynamics, wherein members of the former believe members of the latter are not only misinformed, but ignorant at best and evil at worst. More troublingly, it ignites a vicious cycle: The out-group (in this case, conservatives) turns its knives toward the institution, which reduces faith in the university system and strengthens intellectual silos on campus. The outcome of activism trumping competitive inquiry is what Arthur Brooks in his 2019 book Love Your Enemies called a "culture of contempt."

CONTEMPT ON CAMPUS

According to philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, contempt is "the unsullied conviction of the worthlessness of another." Researchers describe contempt as a combination of anger and disgust, which can destroy loving relationships as well as civility between strangers.

A culture of contempt has escalated in the United States for the past two decades. This is not just a question of ideological differences, which are required if scholars are to engage in truly competitive inquiry. Rather, it has to do with the belief that those with whom one disagrees are worthy of contempt. Psychologists studying contempt and polarization cite the rise of "motive-attribution asymmetry" — in which one side to a dispute believes he is motivated by love and that his ideological opponents are motivated by hate — as a driver of this phenomenon. Like the erstwhile culture of persuasion, the culture of contempt has expanded beyond the university, but campuses provide a good case study of the trend.

Examples of a culture of contempt at universities are not hard to find. Just this past year, we have seen it play out on American campuses surrounding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. When progressive students pushed for a ceasefire, some conservative students considered their pleas synonymous with support for terrorism and genocide. When conservative students signaled support for Israel, some progressive students accused them of being pseudo-warmongers who were unbothered by — or even keen to see — Palestinian civilian deaths. Those of us acting in good faith understand that neither accusation holds water for the overwhelming majority of activists on either side.

The problem is this: If one believes the other side is motivated by hate, there is no need for productive dialogue. Indeed, under this dynamic, dialogue represents a kind of capitulation to the enemy. Those with whom we disagree ought to be silenced, condemned, and cast out, lest their nefarious ideas gain traction.

In this way, the culture of contempt represents the antithesis of the Enlightenment values on which the modern university was founded. Coercion overpowers persuasion. Activism trumps competitive inquiry. And academic freedom is dead on arrival.

THE WAY FORWARD

Despite the above trends, there is good news. In a 2018 study of political attitudes, the research non-profit More in Common found that 86% of Americans say they are tired of how divided we have become as a country. Large majorities support compromise. This offers us a major opportunity for social innovation.

Rather than focusing on how large institutions might change to meet this demand — reforms that few of us are in any position to instantiate — I will hone in on what each of us, especially those of us working in academic institutions, can do to exploit this opportunity.

First, we must stop taking sides in the domestic culture war. This is undoubtedly a controversial proposition. Recently, on the wall at one major university, I saw these words from Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel: "We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere."

As important as this lesson was in Wiesel's life, this is not a one-size-fits-all truth for society. In academia, as Haidt and Lukianoff noted, it tends to inflate ordinary differences into a battle of good versus evil, every reasonable debate into an existential struggle. It transforms Ingersoll's metaphorical heresy into literal heresy, justifying exclusion of those who might expose errors in conventional wisdom (as heretical thinking has so often done). As the Kalven Report reminds universities, remaining neutral is not tantamount to cowardice; instead, it upholds Enlightenment values: "The neutrality of the university as an institution arises...not from a lack of courage nor out of indifference and insensitivity. It arises out of respect for free inquiry and the obligation to cherish a diversity of viewpoints."

There are two ways to avoid taking sides on the controversies of the day. The easier route is to set personal or institutional standards that favor deep inquiry over activism. The more difficult route is to openly celebrate ideological heresy by vigorously defending ideas and approaches that differ from our own. Both options are well worth pursuing.

Second, we need to deepen the concept of diversity in our institutions. The push for diversity has done wonders for the intellectual climate of academia in that opportunity has been extended to people of all demographic groups with a range of life experiences. But as the evidence above shows, we have simultaneously narrowed viewpoint diversity and decreased inclusivity through the professional and social threats that come with holding a view that differs from the prevailing orthodoxy.

How, then, can we broaden intellectual diversity? In his recent essay in the Harvard Crimson, Tyler VanderWeele, the director of Harvard's Human Flourishing Program, argued that universities should "try particularly hard to hire faculty who hold disfavored or controversial views when those views are held by a large portion of the population, have not been clearly refuted, and influence culture and policy." This might mean hiring a pro-life scholar in public-health departments, or a sociology scholar who studies the benefits of the nuclear family. VanderWeele pointed to research that shows how differing opinions help scholars and students find common ground over contentious issues.

We needn't reinvent the wheel to achieve these goals. Indeed, a few academic institutions have already begun to renew their campuses' intellectual diversity. The University of Texas at Austin recently launched the Civitas Institute, a center dedicated to free thought and expression. The University of Missouri's Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy welcomes all viewpoints surrounding America's founding, and its scholars pride themselves on depolarizing issues surrounding this contentious topic. Even at Harvard, where I work as a researcher, progress has occurred. During the spring semester of 2024, the Kennedy School's Tarek Masoud launched the Middle East Dialogues series, which brought together scholars with varying views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Harvard recently outlined a fresh institutional policy that echoes the Kalven Report, pledging that the university, as an institution, will no longer take stances on controversies of the day.

These efforts are necessary but insufficient. For the university to once again champion Enlightenment thinking — for it to take seriously the pursuit, rather than the proclamation, of truth — university leaders must recognize that truth indeed "springs from argument among friends." This means institutionalizing a fearless brand of intellectual tolerance in which we celebrate ideas different from our own while simultaneously arguing against those ideas. It means favoring competitive inquiry over activism. And it means overcoming the culture of contempt by resisting our inclination to adopt motive-attribution asymmetry.

To be sure, many of these steps ought to be taken by university leadership. But as engaged citizens of universities, we can implement these rules for ourselves at this very moment. By bolstering Enlightenment ideals, such strategies will revive the university, which is a first step in healing a culture beset by distrust, anger, and contempt.

EMBRACING HOPE

Human beings are ever prone to a major fallacy: believing we are living through uniquely troubling times. This makes the future appear bleak and scary. But as students of history, we ought to remember the most hopeful truth of all: that our circumstances are not terribly unique, and that they are in many ways better than times of old.

The story of the university is a case in point. The medieval university was marked by illiberalism and violence toward those who questioned the prevailing orthodoxy. The Enlightenment turned the tide, allowing academic freedom and competitive inquiry to rise to prominence. While today's university is witnessing a surge of illiberalism, we have not regressed to the 16th century, when coercive monarchs executed dissenters on university grounds.

Moving forward, there is no need for doomsaying. The university will not crumble tomorrow, nor has it forgotten the lessons of the Enlightenment. But we should eye history with care, recognizing that the university's swing from illiberalism to liberalism was driven by the extent to which competitive inquiry flourished on campus. Our challenge today is to emulate Enlightenment scholars and help it flourish once again.