Reversing Social Disintegration

The United States is suffering from significant social disintegration. Social mobility is declining, as are workforce-participation rates. Drug abuse is rampant, and suicide rates have risen dramatically. Life expectancy has been dropping since 2014, the first time such a trend has appeared since World War I and the Spanish influenza epidemic a century ago.

Interpretations of causes and recommendations for remedies vary significantly, especially as one moves across the political spectrum. There is a long list of initiatives, both public and private, that have tried to address aspects of the problem — all without success. Expansions in health-care coverage have not reversed the depressing health statistics for the white working class. Improvements in educational opportunity have not reversed decades of decline in social mobility. New training schemes and income-support policies have not reversed declining workforce-participation rates. And increases in the number of non-governmental organizations working on some aspect of social breakdown have not reversed its growth.

These remedies have failed because they have not addressed the causes of social disintegration: changes in the broader ecosystem of ideas, institutions, relationships, and norms that shape behavior. More specifically, they don't address the drivers of the decline of marriage in America.

A strong marriage provides basic family stability, affecting a wide range of social outcomes as it imbues men and women with meaning and moral obligation. Marriage positively influences health, incomes, social mobility, poverty rates, inequality, happiness, crime rates, and the physical, emotional, and academic well-being of children. The unattached are at greater risk of adopting destructive patterns and suffering from the ills of loneliness. Men are disproportionally affected; the health benefits of marriage for men are greater than those for women (though women realize gains too). Conversely, as W. Bradford Wilcox notes, "When marriage is weak within a community, there are negative externalities that seem to flow from that...we know that crime is higher in communities with fewer married fathers, we know that parents are less involved in schools, we know that the ability is lower to support kids." Boys are especially likely to have behavioral problems and lower student achievement if they grow up in an unstable family environment.

While some efforts have improved marriage rates and family stability within particular neighborhoods (often in partnership with religious leaders or groups), they have done so in a way that is either very labor intensive, expensive, or dependent on a particular individual — none of which can be translated into programs that can reach the millions of families in need of help. For an initiative to have a chance at "scalability," it would have to be effective for a reasonably large group of people (at least hundreds of thousands) at a reasonably low cost per person or family. In addition, such a program should ideally work over a relatively short time period (less than five years), in order to prove its worth to policymakers in time to get support for expansion.

Examples of such successes are rare. But they do exist, and it is worth our while to learn from them. The Philanthropy Roundtable, a nonprofit advising philanthropists and organizing issue-specific programs, executed a project that showed just such potential, reducing divorce rates in Jacksonville, Florida, in about two years through its Culture of Freedom Initiative (COFI). The program, which has recently become an independent nonprofit organization called Communio, used the latest marketing techniques to "microtarget" outreach, engaged local churches to maximize its reach and influence, and deployed skills training to better prepare individuals and couples for the challenges they might face. COFI highlights how employing systems thinking and leveraging the latest in technology and data sciences can lead to significant progress in addressing our urgent marriage crisis.

THE DECLINE OF MARRIAGE

The decline of marriage as a social institution has been well documented. According to the Pew Research Center, the share of adults who are married has declined from almost three-quarters in 1960 to just one-half today. The share who have never been married has also risen, reaching a record one in five. This has led to a "decoupling of marriage and childbearing," with around two-fifths of all births occurring to single women — another all-time high. Partly as a result, the percentage of children growing up with both their married parents has dropped to one-half.

Such dire statistics are especially pronounced among the less educated, creating what scholars Charles Murray and Robert Putnam have identified as a class divide in marriage and family culture. The chasm between those from higher-income (or higher-educated) groups and those from lower-income (or lower-educated) groups with regard to marriage and single parenthood presents an enormous challenge for anyone hoping to improve the lives of the latter. The gap is daunting; to take just one example, while only about one-tenth of new mothers with a college degree were unmarried in 2011, almost three in five new mothers without a high-school diploma were single.

Much of this decline can be traced to how marriage as a social institution has transformed over the past half-century. Once a pillar institution of society — promoting procreation, self-discipline, the well-being of children, and the build-up of wealth — marriage today is primarily a legal contract that provides rights to the two parties involved. The obligations underpinning it have all but dissolved. Other objectives that this institution once encouraged have been pushed aside to make room for an approach that maximizes individual freedom. While this has brought benefits to some — those in unhappy marriages, for example, and LGBT people who want to marry — society as a whole, as well as many individuals and especially children, are left without many of the public goods that marriage used to provide.

While social and economic forces explain some of the shift, changes in culture and norms have played a major role. People are more self-focused, more dependent on the state, and more influenced by an ideology that de-emphasizes or even attacks familism. Alterations in sexual mores, expectations related to marriage, ideas about individual autonomy and choice, roles for women in society and the workplace, and norms related to family life have all contributed, as have declines in the dense social ties and obligations that community life used to entail.

Some of these changes were inevitable due to the increasing urbanization, bureaucratization, marketization, centralization, and mobility that have transformed societies around the globe. But the weakening of marriage as a social institution is much more marked in the West, and in the United States in particular, than in other parts of the world. Secularization and individualization have gone much further in the West than elsewhere, leading to substantially different ideas, norms, and social dynamics. Western countries, for instance, have far higher rates of children born out of wedlock than Asian and Middle Eastern countries because of the weakening of the institutions that support marriage. While two out of every five children are born to unmarried mothers in the United States, only one in 50 are in Japan, which is just as modern economically, politically, and culturally. The differences are of course even more pronounced when it comes to non-liberal regimes. In China, India, Indonesia, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia, the rate is 1% or less. That's obviously not an argument for adopting their approaches to family or individual liberty, only an illustration of the vast difference that culture can make.

Policymakers and public intellectuals have been talking about this problem since the mid-1960s, and a handful of policy initiatives have been attempted or proposed in recent decades to directly strengthen marriage and families. These have either been ineffective or, at best, have made only modest differences. While there have been a few important successes (for instance, a reduction in teenage pregnancies), nothing has been able to halt or alter the troubling overall trends. The general lack of urgency on the matter is perplexing given the centrality of marriage and families to overall societal health.

The George W. Bush administration did champion legislation, enacted in 2005, that provided up to $150 million for Healthy Marriage Promotion and Responsible Fatherhood grants. Using this money, it launched a number of modest initiatives designed to strengthen marriage. Later, a $75-million-a-year grant program funded 61 local marriage projects, but the results were limited. Evaluative studies were launched to assess three sets of programs: one focused on improving the relationships and marriage prospects of unmarried couples having babies; a second focused on improving the quality and sustainability of married couples having babies; and a third focused on strengthening existing marriages and promoting ideas about the advantages of marriage on a community-wide basis. Evaluators concluded that some modestly positive results were achieved with the second set of programs, and in some locations with the first set. However, given the high costs of the projects (estimated at between $9,000 and $11,000 per couple), the results were not significant enough to conclude that anything but more experimentation and refinement of existing programming are needed to achieve results at a cost that is sustainable over time and scalable over a large population.

The Obama administration continued this funding, with $75 million allocated to each leg of its Healthy Marriage and Responsible Fatherhood initiative starting in 2015. In the first year of what was planned to be a five-year program, 91 organizations received grants to "promote healthy marriage and relationship education, responsible fatherhood, and reentry services for currently or formerly incarcerated fathers." Rigorous evaluations have so far been limited to a relatively small subset of the total number of grantees.

Efforts have not been limited to government initiatives. Many non-governmental organizations, especially those with religious affiliations, consider supporting marriage and family life part of their core missions; they run programs designed to bolster marriage and act as informal family counselors. But there is little data on the success of these programs, and even if we assume they have some positive effects, they have not stemmed a decades-long decline in marriage and social outcomes. If some of these have had a more substantial impact, they have apparently not done it in a way that could be expanded to reach beyond their relatively small pockets of success. Many depend on mentoring, relationship building, and volunteers, and are perhaps too labor-intensive to reach a large number of people.

As for broader public policies that can affect the general conditions that couples face, some public interventions have the potential to at least enhance the chance that families will be formed and maintained. According to Ron Haskins of the Brookings Institution, these include reducing the marriage penalties that exist in means-tested benefits programs; supplementing the wages of poorly educated men; offering long-acting, reversible forms of birth control to low-income women; testing and then supplying or subsidizing the most effective relationship-training programs; expanding work opportunities for poorly educated men; reducing the incarceration rate; and extending subsidies for child care. But even if all of these were implemented, they would do little to challenge the social dynamics that play an outsized role in the marriage crisis.

A SYSTEMS APPROACH TO SOCIAL CHANGE

Isolated programs and even broad public policies are unlikely to reverse marriage trends (or, for that matter, the trends evident in a whole host of other social institutions and constructive norms that are similarly in decline). Policymakers and other actors must systematically engage with the ideas, values, and norms that affect the overarching cultural narrative, as well as the specific relationships, social networks, and community leaders that comprise local contexts. As I have previously written in these pages, a systems approach recognizes that individual choices are embedded within a large system of interlocking institutions and ideas that shape how they are made.

Attempts to improve marriage outcomes using linear thinking — which assumes that the connections between the problems and their causes are obvious and can be tackled independently with little concern for context and the interrelationship of many variables — will inevitably fail, because they treat the symptoms (or products) of the system and not the interacting components that make it up.

The theory of change that informs COFI (and now Communio) is based on systems thinking instead of linear thinking. It builds on an analysis of the success factors behind campaigns to reduce smoking, teenage pregnancy, and drunk driving — all of which involved sustained, strategic, holistic efforts to shift norms and behavior. According to this theory of change, the social system that affects marriage consists of five interacting components.

The first is intellectuals and academia, which shape ideas and frame what a society values, how its challenges are addressed, and what its young people aspire to. Although far removed from the daily lives of the average person, these ideas can ultimately influence how important institutions and actors behave and are viewed.

The second, cultural storytelling, is composed of the stories told by news organizations, the entertainment industry, and other media — both high and low — that translate ideas for a wide audience. These influence social conceptions, norms, expectations, and, ultimately, behavior. For example, television has been shown to influence how many children families have and the lifestyle aspirations of young women.

The third component is advocacy groups. A wide variety of organizations — the National Rifle Association, the La Leche League, churches — try to directly influence individual behavior through government policy, community drives, and education, as well as through encouragement and shame. Some may be trying to change an existing paradigm; others may be trying to protect or reinforce an institution. While not all activities conducted by these groups involve direct contact with people, many of them do.

The fourth, authority figures, are the people in a community or network that have a significant influence on what ideas and norms are adopted. Doctors, lawyers, pastors, financial planners, therapists, teachers, and so forth are sufficiently trusted because of their expertise and status in one area; consequently, their advice and counsel on a wide range of subjects is heeded.

The fifth component is interpersonal relationships. Friends and family often exercise the strongest influence on individual decisions. These social networks set examples, standards, and norms that members emulate. The importance of such actors has long been recognized by other elements of the social system, as evidenced by campaigns such as those to combat drunk driving with the slogan "friends don't let friends drive drunk."

Although various analyses will break down these components differently, the fundamental picture is the same: Each person — and each family — is embedded in a larger social system. Each part of this system works in conjunction with the others in an interactive fashion. No element stands on its own.

In general, these individual components must be enhanced simultaneously in order to have an impact, because they each play a role in the effectiveness of other parts of the system. Their interaction creates a network effect on the environment; the more functional each piece is, the better the others generally will work and the more supportive of marriage the overall ecosystem will be. The reverse is also true: Resistance to change in one area can easily impede the development of other components or the health of the overall ecosystem.

The shift in attitudes toward smoking demonstrates what is necessary to effect such a major change, and how long the effort must be sustained. The anti-smoking campaign involved a series of systemic interventions — including education, advertising, the media, taxes, legal changes, and lawsuits — that incrementally and cumulatively changed society's behavior in a major way. But it took decades and succeeded only because the effort was sustained and broad, including cooperation from Washington and even Hollywood.

Recognizing the necessity of such broad coordination, COFI was designed around the idea that religion should play an important role in any attempt to strengthen marriage as a social institution. Religion is uniquely equipped to influence many of the five components in a way that no other institution or sector could. A broader approach involving many more actors working in parallel with one another would be ideal, of course, but that is well beyond what such a small program could expect to achieve. And given society's apparent ambivalence regarding the importance of marriage, such wide cooperation is unlikely in any case.

Organized religion, through its teaching and programming, provides a coherent cultural framework built around ideas and stories that consistently emphasizes the importance of marriage and family; its various institutions, authority figures, informal support networks, and relationships all aim to strengthen families in one form or another. In their most robust forms, religion and marriage work, in the words of Mary Eberstadt, as "the double helix of society." Of course, these various components are only fully activated when individuals or couples are deeply embedded in a church (or other worship) community. The more embedded they are — and the stronger the community, with its guiding stories, social ties, and bonding rituals — the more influence the community has on their lives. Those on the periphery or those in weak communities will be much less affected.

The relationship between religion and family has been well documented. Regular attendance at religious services is linked to strong marriages, stable family life, and well-behaved children; reductions in the incidence of domestic abuse, crime, and addiction; and increases in physical health, mental health, education levels, and longevity. And, as Patrick Fagan summarizes, "these effects are intergenerational, as grandparents and parents pass on the benefits to the next generations."

On a practical level, for COFI, churches not only provide relatively comprehensive coverage across most of the ecosystem, but they also have a much broader geographical reach and lower cost than any other organization working in the target neighborhoods or addressing the issue in general. And churches' longstanding natural interest in promoting strong marriages and families makes them very willing partners. As such, they offer a unique combination of cultural and moral frameworks, norms, networks, mentors, models, infrastructure, practical services, and efficiency that is unmatched elsewhere.

This does not mean that "unchurched" individuals and couples should be ignored. On the contrary, the best candidates for outreach are those who do not belong to a church (or are only weakly affiliated with a particular church community) but have the potential to increase their commitment. Those who are unchurched and unlikely to want to be involved with a church have been purposely excluded from COFI's activities to date; the cost to reach them, both financial and practical, is substantially higher, at least partly because secular community-based organizations promoting marriage tend to be less "sticky" than religious ones. (These groups of people can now be identified through data analytics, as explained in more detail below.) A third group consists of individuals strongly embedded within church communities; these people are likely to already have relatively robust marriage norms and support networks and be less in need of outreach unless specifically identified as being at risk.

DEMAND-DRIVEN ENGAGEMENT

COFI's core approach centers on the ideas that faith and family are reinforcing, that churchgoers are more likely to form and maintain strong marriages, and that married couples are more likely to attend church. It has therefore always worked with church communities, though its strategy for leveraging religion to buttress marriage has evolved significantly. Whereas it initially sought to work with a large number of organizations, assuming that increasing the number of marriage-promotion programs alone would influence outcomes (a supply-side approach), this approach was unwieldy, expensive, and not necessarily effective. COFI therefore switched to a more targeted and multifaceted effort aimed at the population that would be most likely to benefit from the initiative. Targeted couples had a high propensity both to get divorced and to accept an invitation to attend an event at a church, even though they were not members. This demand-driven approach has proven very effective in reducing the divorce rate in a relatively short period of time at the Jacksonville, Florida, test site, where it was best coordinated and implemented. The lessons learned from COFI's adaptation may be as important as the set of instruments used.

COFI launched in 2016 in three test locations: Dayton, Ohio; Phoenix, Arizona; and Jacksonville. Its goal was to boost one or more of the following outcomes: number of people getting married, number of people staying married, number of children being born into married homes, and regular attendance at houses of worship. The last item was assumed to indirectly promote the first three. The cities were chosen from a longer list of candidates because their marriage outcomes had ample room for improvement but were far from being the worst cases.

From the start, the program had three core ideas. First, religious participation has a major impact on family life. Second, some local churches and nonprofits were already making an impact, and this impact could be enhanced and scaled up to reach more people more effectively. And third, sophisticated data-analytics tools could be leveraged to shape opinions and behaviors, similar to how they are used by consumer-product and political-marketing companies. At first, COFI partnered with content providers as well as churches and other front-line groups to increase the availability of and access to a wide range of marriage and faith-expanding programs (which the former supplied in the latter's locations). COFI assumed that such programming would by itself have a large impact. It tried to supplement these programs by leveraging the broad insights garnered from data analytics to identify which programs would be most successful in which areas. COFI invested in its own research and data-marketing efforts, and gave grants to content providers that could build up programming in the three cities.

Over approximately the first 24 months of the program, more than 150,000 people attended one of a variety of classes (which averaged eight hours in length) on topics such as dating, marriage preparation, marriage enrichment, communication, overcoming marriage conflicts, parenting, fatherhood, workforce preparation, or faith development. The program developed relationships with over 430 organizations.

But simply increasing the supply of programming proved costly, and it was not nearly effective enough to scale up — a finding similar to those of the government-run programs described above. In fact, though COFI differed from the federal programs in many ways — it focused on religious organizations (which made up roughly 70% of the front-line groups), had access to much better data (which improved efficiency), and was much cheaper ($261 per family versus $5,000) — its outcomes were more or less the same.

After just a few months of seeing the results of this initial effort and learning from exchanges with its partners, COFI switched to a more demand-driven model, using data to steer its efforts. Churches and other front-line organizations were provided with enough information to enable them to identify family, marital, and faith challenges in the geographical areas around their communities. This generated a desire among the partner organizations to launch new events and programs to address the problems uncovered in the data.

Instead of paying content providers, support was given to churches and other front-line organizations. Per-student cost was the key driver of resource allocation. In addition, the data marketing was decentralized: Each partnering organization had access to a dashboard of aggregated information that could be categorized by location (a particular zip code, for instance, or within five miles of a particular church) and risk factor (for example, couples at high risk of divorce). This catalyzed and focused local activity in a way that was not possible earlier; efforts could be targeted at precisely the people most likely to need and engage with the program. In addition, five organizations were designated as "mobilizers" to help coordinate efforts across many front-line groups.

Once these changes were in place, the cost — both in terms of volunteer and financial resources — of enrolling individuals in programming (and in other support services offered by the churches and other organizations) dropped significantly because targets could be better prioritized. In 2017, more than twice as many people (103,000 versus 47,000) attended classes at 80% less cost ($45 per person versus $261) compared to 2016. Increased fundraising and collections raised revenue, while improved productivity lowered costs, all of which incentivized front-line organizations not only to take over the costs of the programming (and at least some of the data marketing) but to expand it. Beginning in 2017, 80 of the front-line organizations started to make their own investments.

USING BIG DATA FOR GOOD

Data analytics is crucial to targeting those most in need. Just as large technology firms and some political campaigns have used "Big Data" to target and change the behavior of consumers and voters, COFI used advanced analytical tools to assist groups already working to strengthen marriage and to address various other aspects of social breakdown. It partnered with a brand-strategy firm that usually works with large multinational corporations to understand the emotional drivers and barriers related to marriage among millennials, the primary target demographic (the group encompassed 18- to 35-year-olds when the initiative launched). It also partnered with marketing data firms that specialize in microtargeting to shape its outreach and advertising. As J. P. De Gance, founder and president of Communio (and formerly the executive vice president of the Philanthropy Roundtable, the program's initial sponsor), explains, "Microtargeted marketing has long existed in the commercial world. It's used throughout the political world. But in a lot of ways, the family and faith sector is still living, technologically, in the 1990s. This project is bringing it forward."

With the assistance of these companies, COFI developed a predictive model that uses algorithms and various types of data to project how particular models of behavior and character traits might identify individuals most likely to divorce, become single parents, or react favorably to an invitation from a church — as well as those struggling with a wide range of other challenges, such as anxiety, financial stress, spiritual crises, health crises, and substance abuse. The model for divorce, for example, identified dozens of factors (among hundreds examined) that robustly correlated. It showed, for example, that an uptick in buying television dinners or gym memberships, or spending on thrill-oriented activities like adventure travel, suggested a couple was at risk and should be targeted for invitation to one of the classes and hopefully entry into a web of social-support activities.

With the help of the data dashboards, institutions could determine what activities were most useful within their sphere of influence (say, a five-mile radius) and then microtarget individuals for direct mail, online advertising, or social-media outreach. (The names of those microtargeted were not directly provided on privacy grounds; instead they were kept by a COFI partner for enhanced data security.) Facebook and Google were used for approximately two-thirds of the digital advertising.

The key was to leverage the data to maximize the use of the social system around churches and other front-line providers. These groups provided ideas, cultural narratives, advocacy organizations, authority figures, and interpersonal relationships (the five components listed above) to change behavior. But as islands in the much larger sociocultural sea, churches' microtargeting of individuals and efficient use of limited resources were crucial.

Jacksonville proved to be the most successful of the three locales, at least partly because of the effectiveness and focus of two local mobilizers. Live the Life, a Florida nonprofit dedicated to strengthening family life, played a crucial role as mobilizer, consultant, content provider, and coordinator. It delivered almost half of the classes in the area, while also advising churches on how to create "self-sustaining comprehensive marriage ministries." It also organized regular activities that brought together 40 of the area's 93 front-line organizations to share experiences and data and develop informal partnerships in various areas.

Another mobilizer, Alpha — an "evangelization consultant" dedicated to helping churches reach the unchurched — worked to increase the number of individuals attending a place of worship, which has a strong influence on marriage outcomes. It substantially increased the number of churches in the program and then used the churches' facilities to run a series of conversations related to faith; these talks increased the number of participants regularly attending religious services. Meanwhile, COFI ran a parallel internet campaign aimed at strengthening relationships and family life, reducing divorce, and increasing involvement with organizations working to improve these goals. The campaign garnered more than 20 million impressions.

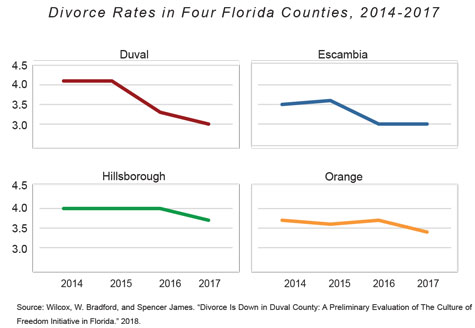

The results were impressive in reducing divorce rates, something no other similar initiative run and tested at the same scale can say. As an evaluation conducted by W. Bradford Wilcox and Spencer James concluded, "[T]he efforts undertaken by COFI in Jacksonville appear to have had a marked effect on the divorce rate in Duval County [where Jacksonville is located]" when compared to three peer counties. (See the chart below.) The program "has had an exceptional impact on marital stability in Duval County. Since 2016, the county has witnessed a remarkable decline in divorce: from 2015 to 2017, the divorce rate fell 28 percent....[W]e have rarely seen changes of this size in family trends over such a short period of time."

Though it has had marked success in reducing divorce rates, COFI has had more mixed results in its three other priority areas. The initiative did not increase marriage rates at all; Wilcox and James suggest that this is because the initiative "did not do much to directly promote marriage per se," and instead focused on strengthening existing marriages and relationships. Alternatively, it could be "because the effort ended up encouraging Jacksonville residents considering marriage to proceed more carefully." It may also be easier to use data analytics to identify marriages at risk than to identify couples who are marriage candidates.

The initiative has also not yet developed a replicable and scalable method to reduce out-of-wedlock births, another of COFI's four goals. Work on this part of the program started in late 2017, and data on these particular outcomes are available only after a substantial time lag, making program evaluation and adaptation slower. COFI is, however, making the objective a priority and is trying to apply lessons learned elsewhere. The recently launched MarriageB4Carriage campaign in Phoenix will use a similar approach to the one that succeeded in reducing divorce rates in Jacksonville. Working with local partner Family Bridges, COFI is combining microtargeted digital ads and face-to-face education programs for 17- to 28-year-olds in zip codes with the highest out-of-wedlock birth rates around Phoenix. The goal is to teach the importance of getting a high-school diploma and a job before marrying and having kids — what Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill have named the "success sequence."

Although the 2016-2018 initiative did not see positive changes in the success sequence and marriage rate, it did see a rise in regular church attendance — COFI's fourth goal. Over 130 churches in the three cities have seen significant and sustained growth — 25% to 30% and higher — in attendance at Sunday services after targeted digital advertising and volunteer door-knocking campaigns. Given that attending church regularly significantly increases the chance that someone will get and stay married, such figures are likely to have a positive impact on other indicators over time.

Of course, two years are not sufficient to judge the effectiveness of this initiative. These results are preliminary; they would need to be monitored over a longer time period and tested over a larger population before they could be convincing. But the experience of COFI so far does clearly suggest that this combination of interventions can reverse the decline in constructive social norms. It is unique both in its use of data and microtargeting to identify couples in need of assistance, and in the comprehensiveness of the interventions it brings to bear on the various components of the social system, all at significant scale and low cost. Although much work lies ahead to further refine and prove its model, the success of its systems approach contrasts sharply with what other programs have been able to accomplish.

MARRIAGE AS A PUBLIC GOOD

The most intractable aspect of the marriage crisis afflicting American society is the lack of recognition that there is a crisis at all. The possible explanations are many. It could be because the elite and educated classes have remained immune to — even segregated from — the crisis. It could be because the natural constituency for such urgency — the right — has tilted too far toward libertarianism, or because feminist discourse has taken over academia and the broader cultural narrative. It could be because the reigning cultural ideology emphasizes individual agency and rights and de-emphasizes the importance of any social institution. It is likely a combination of all four.

No matter which trend bears the most responsibility, public and private attempts to address the challenge have been inconceivably small given the scope of the damage. Too often, attempts are condemned as judgmental or are disregarded as useless given the magnitude of the crisis or the inevitability of the social changes and shifting norms. Instead, policymakers and social reformers treat the products — poverty, crime, and poor academic performance, to name just a few — while ignoring the broader social system and norms, despite overwhelming data showing these are the source of the problem. In any case, the definition of marriage itself has become so controversial that it is nearly impossible to get bipartisan support for programs that encourage and support traditional marriage in the first place.

Systems thinking can help change this dynamic. It is politically neutral and is considered best practice in many sectors (including health care). Most important, any serious systems approach to tackling social problems would have to include a greater focus on marriage. Such an approach would challenge the conventional thinking that infuses most debates in this area, while forcing a deeper, longer-term focus on underlying societal dynamics — prerequisites for a more honest public discussion of the marriage crisis.

COFI shows what creative philanthropy can do when leveraging systems thinking, the latest marketing techniques, and a network of front-line partners. But it also highlights the need for greater engagement with different parts of society, and for more partnerships among faith leaders, policymakers, and intellectuals, along with media and NGOs. Substantial change to our marriage culture is unlikely unless intellectual leaders, cultural storytellers, advocacy organizations, and authority figures make repairing the social fabric the priority it deserves to be.