Rethinking Tax Benefits for Home Owners

The individual income-tax code offers a multitude of benefits for home owners. The largest in dollar terms, and the most apparent to taxpayers, is the mortgage-interest deduction, which allows home owners to deduct the interest paid on up to a $1 million mortgage and up to $100,000 in additional debt backed by home equity. But the tax code also tilts the balance toward home owners by allowing a deduction for state and local property taxes and exempting from taxes the capital gains from the sale of a home. These preferences for home ownership fall under the umbrella of "tax expenditures," or provisions that create special benefits by lowering tax liabilities. Tax expenditures technically reduce the amount of taxes paid, but they resemble direct spending programs more than they do typical tax laws. The tax benefits for home ownership are thus essentially subsidies.

Although tax expenditures for housing are not real line items in a budget the way other spending programs are, they have real effects on the economy by creating incentives, lowering receipts, raising the debt, and causing tax rates to be higher than they otherwise would be. The cost of the tax benefits for owner-occupied housing adds up to about $175 billion annually, with the mortgage-interest deduction alone costing the Treasury roughly $100 billion. The five-year costs of these tax benefits total well over $1 trillion. To put this amount in perspective, one year of tax benefits for owner-occupied housing costs more than the discretionary budgets of the departments of Education, Homeland Security, Energy, and Agriculture combined.

Proponents of these generous tax benefits often justify them by arguing that they encourage home ownership, which in turn is said to offer society all manner of social and civic benefits. In reality, however, it is far from clear whether mass home ownership is inherently beneficial to our society or even to individual home owners. But whatever the merits of owning a home, the data regarding the reach and distribution of the various tax benefits we offer owners show that these benefits do not in fact encourage such ownership in any meaningful way. Most Americans receive no benefit from the preferential tax treatment of home ownership, and those who do see such benefits tend to be high-income earners who own large, expensive homes, and who are therefore unlikely to be on the fence about whether to buy or rent.

In fact, the tax benefits afforded to home owners are highly regressive, extremely expensive, and of little obvious value to society at large. Even if we do want to encourage home ownership through the tax code — and it is by no means obvious that we should — there are far better ways to do so. By considering the flaws in the tax treatment of housing and examining how our housing-related tax benefits are distributed across incomes and across the country, we may come to see how these policies might be transformed to better serve owners, renters, and taxpayers.

WHO BENEFITS?

The value of the tax benefits for home ownership depends on housing costs and income, since the breaks are larger for larger mortgages and amount to more savings for people in higher tax brackets. This leads to, among other things, wide variations in benefits among states and metropolitan areas, as incomes and home prices differ substantially across the country. Incomes and home prices tend to be higher in the suburbs of major cities and along the East and West Coasts, while the downtown neighborhoods and inner-ring suburbs of most cities as well as the more rural regions of the country tend to have incomes and home prices that are lower.

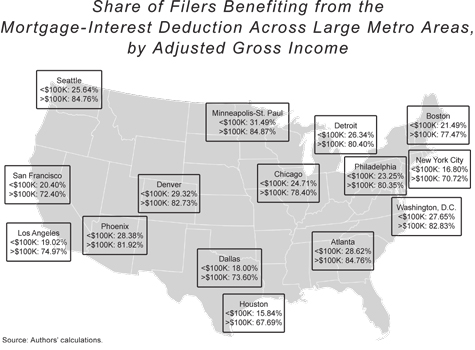

A look at the distribution of the largest tax break for housing, the mortgage-interest deduction, reveals a stark difference between the benefit that accrues to those earning more than $100,000 a year and those earning less. The difference between taxpayers on either side of that divide is generally consistent across metropolitan areas of the country. In most cities, tax filers with an income above $100,000 are between three and four times more likely to take advantage of the mortgage-interest deduction than are taxpayers below that income level.

At first glance, these data appear to be consistent with the story that the mortgage-interest deduction benefits a vast majority of taxpayers: After all, more than 80% of taxpayers earning over $100,000 in Atlanta, Denver, Detroit, Minneapolis, Philadelphia, Phoenix, Seattle, and Washington, D.C., claim the deduction. But it is important to recognize that only about 10% of taxpayers have adjusted gross incomes in excess of $100,000. Of those earning below that level, only 25% take advantage of the mortgage-interest deduction.

Among major metropolitan areas, Minneapolis has by far the most taxpayers who earn less than $100,000 but take the deduction, at 31.5%. But even there the gap between taxpayers under and over $100,000 in adjusted gross income is large, as nearly 85% of those earning more than $100,000 benefit from the deduction. Houston has the smallest percentage of taxpayers under $100,000 who benefit from the deduction, with just under 16% receiving any tax savings, while more than four times that proportion of Houston taxpayers earning more than $100,000 benefit from the deduction. Even in areas with relatively more taxpayers claiming the deduction, the percentage of those earning less than $100,000 who benefit from it hovers between 20% and 30%, while the share of tax filers with incomes above that level who benefit is between three and four times larger.

Considering that national opinion polls show support for the mortgage-interest deduction ranging between 60% and 90% of the populace, there seem to be many Americans who believe they benefit from the deduction when they actually do not. This is surely to some extent a function of the popular view that the mortgage-interest deduction increases home values, but in fact, as we shall see, the deduction inflates those values across the board, which should appeal only to people who want to sell their current homes but not buy new ones. Any move away from the deduction would certainly have to involve a gradual and careful transition to avoid deflating that effect too quickly, but home-price inflation hardly justifies the deduction.

The strong public support for the mortgage-interest deduction may also be due in part to the fact that taxpayers think the amount of savings that they receive through the deduction is large compared to the savings that others receive, and that their resulting tax savings are proportionally higher. But most people are surely wrong to think so.

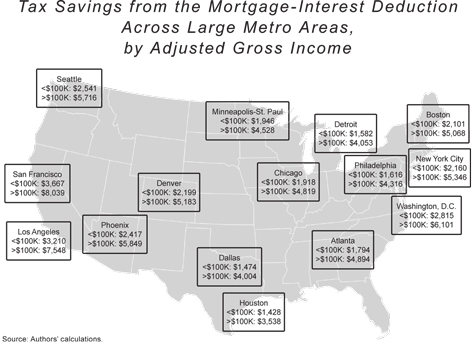

A look at the data shows that there are vast differences among Americans in the amount of tax savings received from the mortgage-interest deduction, but it is a small minority that sees most of the savings. The average tax savings for the 10% of households earning over $100,000 is more than double the savings enjoyed by the 90% of households with incomes below that level. In San Francisco, residents earning over $100,000 save $8,000 a year from the deduction, compared to an average savings of about $3,700 for residents in that area earning under $100,000.

It is also clear that the tax savings from the deduction in places like San Francisco dwarf the savings in other parts of the country, even for those earning over $100,000. For example, the high-income group in Detroit saves just over $4,000 in tax payments as a result of the deduction, just about half the amount saved by high-income home owners in San Francisco. Those earning less than $100,000 in Detroit average a savings of less than half that of the high-income residents there, or about $1,600 annually.

Indeed, the distribution of tax savings from the mortgage-interest deduction makes it clear that people living in certain parts of California enjoy a far greater benefit (regardless of income level) than does the rest of the country. This difference is a function of the high home prices in that state, but even the benefits in high-home-price environments are concentrated among the top 10% of taxpayers.

The average benefit for lower-earning households in places like Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Detroit, Houston, Minneapolis, and Philadelphia doesn't even reach $2,000 per year, while in many other cities the benefit is just slightly more than $2,000 for this income group. Comparing both income groups and metropolitan areas shows clear evidence of the skewed benefits of the deduction and makes it clear that it is a narrow segment of higher-income households living in high-priced areas that benefit most from the policy.

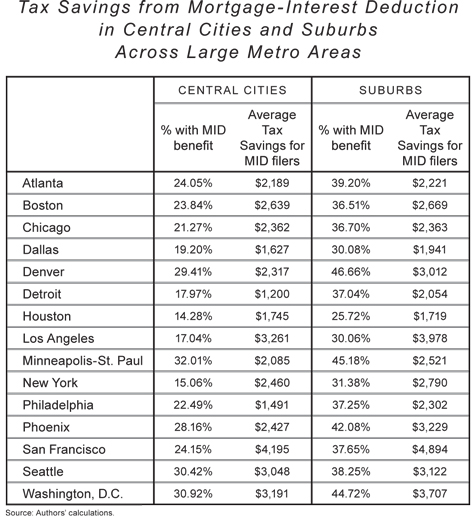

The dramatic variation in benefits across incomes and metropolitan areas is further exacerbated by intra-metropolitan differences in benefits. The structure of most American metropolitan areas — with relatively wealthy exurban areas surrounding less well-to-do inner-ring suburbs and poorer inner-city areas — yields another dimension on which the benefits from the mortgage-interest deduction differ quite dramatically.

The difference between urban and suburban areas is the largest in Detroit, where twice the proportion of suburbanites claim the deduction as compared to central-city residents. In cities such as Boston, Dallas, Denver, Minneapolis, Phoenix, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., suburban residents are 50% more likely to deduct mortgage interest than central-city residents, and the ratio is slightly higher in Atlanta, Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia.

Still, while suburban taxpayers are more likely to claim the deduction than those living in the center of the city, the average tax savings for the taxpayers who do claim the deduction are roughly the same: The differences in tax savings between suburbanites and central-city residents as a result of the deduction are within $100 for Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Houston, and Seattle, and the largest differences — in Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Phoenix, and San Francisco — are no more than $900.

BENEFITS UPON BENEFITS

The mortgage-interest deduction is the most visible and widely discussed tax break for housing, but it is by no means the only one. Uncle Sam also allows home owners to deduct the amount they pay in state and local property taxes, and most capital gains from a sale of a home is excluded from taxable income. The capital-gains allowance is generous: Most taxpayers are not responsible for income-tax payments upon realizing even a $250,000 gain from the sale of their home.

Of course, the value of the capital-gains allowance is highly dependent on selling a home in a hot housing market. People in areas that experience house-price appreciation greatly benefit from this tax break, while those in areas with slow or negative price growth barely notice its existence. The benefit from the property-tax deduction similarly varies by geography. Not only is the property-tax deduction tied to housing values, but it is also tied to the quality of local public services that are funded through the property tax — especially schools. Areas that spend a lot on schools typically raise that money through the property tax, and residents of those areas are afforded a larger deduction because of it.

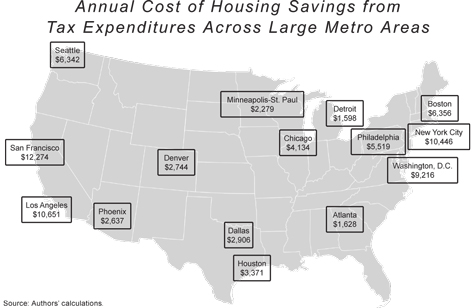

The map below shows how these tax expenditures (including the mortgage-interest deduction) change the annual cost of ownership for taxpayers in different parts of the country. The calculation of cost savings from tax expenditures takes into account differences in income-tax rates, debt-to-value ratios, property taxes, and local home-price inflation, but not differences in interest rates or other costs, such as maintenance and depreciation.

These total cost savings from the preferred tax treatment of housing across metropolitan areas show even larger differences between areas than those revealed by looking at the mortgage-interest deduction alone. The total savings in housing costs from the tax code range from over $12,000 annually in San Francisco to under $1,600 in Detroit. The average annual benefit of housing-related tax expenditures exceeds $10,000 in both New York and Los Angeles, while it is under $3,000 in Atlanta, Dallas, Denver, Minneapolis, and Phoenix. The Washington, D.C., area also has a relatively high benefit at over $9,000 per year, whereas places like Chicago and Houston have comparatively lower benefits, at $4,134 and $3,371 per year, respectively.

Housing tax expenditures are clearly more valuable in places where house prices have maintained strong appreciation like San Francisco and in places with high local property taxes like New York. Places with low property taxes like Houston or negative price appreciation (as Detroit has had until recently) receive very little annual benefit from the package of housing tax expenditures.

WHAT THE BENEFIT BUYS

The skewed distribution of benefits from the mortgage-interest deduction and the larger package of housing-related tax benefits demonstrates that just a handful of areas, and a handful of taxpayers within those areas, receive most of the benefit from these generous provisions. This raises the question of just what society actually gets for $175 billion per year. The answer, it seems, is that we do not get very much.

To begin with, empirical studies have made it reasonably clear that these large tax expenditures do not appreciably increase the home-ownership rate. Economists have examined the data in two different ways — by considering how the generosity of the policies has changed over time and how it varies with geography. Both methods point to the same conclusion: The generosity of the mortgage-interest deduction is not correlated with home-ownership rates.

But if housing-related tax benefits, and especially the deduction for mortgage interest, are not increasing American home-ownership rates, then what function do they serve in housing markets? Evidence shows that, rather than encouraging the purchase of homes by people who might otherwise only rent, the mortgage-interest deduction instead encourages the purchase of larger homes by people who would otherwise own smaller ones. Estimates show that the generosity of this deduction alone increases the average size of homes by between 11% and 18%. This is certainly evident in the size of homes Americans purchase, as the average home purchased today is more than 2,500 square feet — more than 400 square feet larger than the average in 1990 and more than 750 square feet larger than the average in 1980.

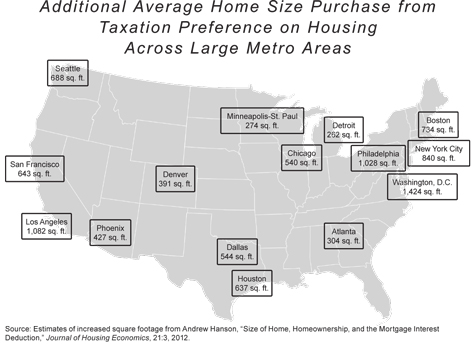

Of course, it is not just the mortgage-interest deduction but the combination of all housing tax preferences that makes a larger home more appealing to buyers. The data on the map below combine the cost savings from all tax expenditures to show how much larger homes are in different parts of the country because of these tax breaks.

The additional square footage purchased because of housing's tax-preferred status varies among metropolitan areas, just as the cost savings from these policies do. At the high end of the spectrum, estimates suggest that homes are substantially larger due to housing tax expenditures — as much as 1,400 square feet larger in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area. In other areas, like Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and New York City, the effect of housing tax expenditures on the size of homes is smaller but still quite significant, encouraging people to buy homes that are at least 800 square feet larger. Even at the bottom of the distribution, tax benefits still have a real effect, increasing home sizes by more than 250 square feet in all metropolitan areas. And it is worth noting that these estimates include only purchases of owner-occupied single-family homes, so they do not account for purchases of larger condominiums and necessarily exclude all rental properties.

Beyond pushing home sizes upward, the tax preferences for home ownership shape home buyers' behavior in several other ways. Because the mortgage-interest deduction can be applied to both a primary and secondary residence, it almost surely encourages those with the necessary means to purchase vacation homes — hardly a great social good worthy of taxpayer subsidies. In addition, the fact that the deduction applies to the portion of a home financed with debt (rather than household savings) encourages more debt financing than would otherwise be the case.

The increase in home sizes, encouragement of second-home purchases, and preference for debt financing are all examples of how housing's tax preferences distort consumer behavior. All of those changes in behavior lead to enormous amounts of misplaced economic activity: If these policies did not exist, consumers would likely purchase smaller homes using less debt. That misplaced economic activity is what economists call deadweight loss — a measure of all of the things that people do too much of as a result of an economic distortion like a subsidy created by the tax code. A recent estimate of the deadweight loss from the mortgage-interest deduction using Internal Revenue Service data from actual tax claims found that it is responsible for between $17 and $38 billion annually in misplaced economic activity.

So why isn't an increase in home ownership among the distortions attributed to the mortgage-interest deduction? The deduction certainly changes the annual cost of owning a home — making it cheaper through the savings on an owner's annual tax bill. But the mortgage-interest deduction does not do a good job of targeting funds to subsidize marginal home owners, or those who are deciding between renting and owning a home. Instead, it provides generous tax breaks to those who would own a home regardless of the tax treatment, even if it might be a slightly smaller home.

The mortgage-interest deduction is not well targeted because it works as a tax deduction, meaning that for every dollar paid in mortgage interest, a taxpayer subtracts one dollar from the income he pays taxes on. The amount a taxpayer saves from the deduction is a function of the top marginal tax rate he pays. Since higher earners tend to pay a higher top rate, the exact same deduction will, in fact, be more valuable to taxpayers at the top of the income distribution. At the same time, using the mortgage-interest deduction requires taxpayers to itemize deductions — meaning they fill out a form listing all of their varied deductions instead of just checking a box to take the standard deduction. Nearly all middle- and low-income taxpayers take the standard deduction, making the subsidy created by the mortgage-interest deduction completely useless to them. The current standard deduction of $12,200 for married couples, while making their tax-filing process simple, makes the mortgage-interest deduction useless for almost anyone truly on the margin between owning and renting.

For middle-class families, the standard deduction is also usually the best option, since it constitutes a sizeable fraction of their income and it would take a lot of spending on tax-deductible goods and services to have itemized deductions that exceed the optional standard deduction. For instance, on a $200,000, 30-year mortgage at 4%, interest payments add up to only $8,000 the first year and gradually decline in subsequent years. If we assume that this family faces a property tax of 1% and gives 2% of its income to charity — roughly the national averages for each — then the three biggest deductions in the code for this prototypical household add up to the standard deduction. In other words, this family would not reduce its tax bill at all by purchasing a house. And for the 90% of all U.S. households with incomes below $146,400 (which was the upper threshold for the 25% tax bracket in 2013), each dollar above the standard deduction reduces their federal tax bill by a mere 25 cents at most. The system of tax expenditures thus offers virtually no incentive for middle-class families to purchase a home.

The difference in average tax savings between income groups can be attributed to both the higher marginal tax rate, which means each dollar deducted from one's taxable income saves more money, and the fact that upper-income taxpayers have 60% more mortgage interest to deduct. They have more interest because they can buy more expensive homes and take on more debt. A doubling of income more than doubles the expected tax savings from the mortgage-interest deduction, as it boosts the family into a higher tax bracket and proportionally increases the amount they can borrow to purchase a home.

A household with an income of $500,000 can afford a $1 million mortgage, while a family earning near the national median income of $51,000 would struggle to afford more than 20% of that. But the tax code awards the $500,000 household that has the larger mortgage a much larger subsidy. A million-dollar mortgage at 4% for this family results in a tax savings of nearly $16,000 a year, or more than ten times that of the family with the national median income buying a house at the median price (about $221,000).

ALTERNATIVE AVENUES

Commonsense reforms to federal tax breaks for housing have been proposed from both sides of the political aisle. President George W. Bush's tax-reform panel as well as President Obama's National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform both recommended scaling back housing's tax-preferred status. For starters, both recommended capping the size of mortgages that qualify for a subsidy. Bush's tax-reform panel recommended a cap based on regional home prices, while Obama's commission recommended lowering the existing cap to a national limit of $500,000. They both also recommended eliminating the deductibility of mortgage interest in favor of a more straightforward tax credit.

Capping the size of mortgages that qualify for the mortgage-interest deduction would work toward limiting the subsidy for purchasing a larger home and reduce much of the geographic and economic disparity in the subsidy. Switching the deduction to a tax credit, where its value would not be a function of income but instead be a flat rate, would further limit the subsidy provided to upper-income taxpayers while simultaneously expanding it at the lower end of the income distribution.

To have a greater effect at the ownership margin, policymakers might also consider making the credit refundable for lower-income taxpayers, which would allow the credit to be part of taxpayers' refunds instead of just reducing their tax liabilities to zero. Other more modest steps toward using subsidy dollars to encourage ownership could include eliminating tax breaks on anything but a primary residence, limiting the amount of housing-capital gains that is exempt from taxation, or capping the tax rate that applies to deductions.

Making the tax treatment of owner-occupied housing less generous would also generate additional revenues that could be used to lower the debt or reduce tax rates. Estimates show that eliminating the mortgage-interest deduction completely would likely generate between $41 and $73 billion annually, even after considering that taxpayers would adjust their behavior in response to the change. Replacing the mortgage-interest deduction with a tax credit, which would work to increase home ownership, would also generate substantial revenues. Even with the reduction in revenues expected from increased use of the benefit by lower-income taxpayers, switching to a 15% tax credit, for instance, would yield between $17 and $25 billion annually.

A 15% tax credit in place of the mortgage-interest deduction would be better targeted to those who are truly on the margin between owning and renting, but it would still be relatively expensive. Other ideas that have been generated at the state level would be much less expensive and may have similar effects on ownership without the unintended consequence of encouraging the purchase of larger homes. For example, the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority offers assistance to first-time home buyers up to a certain income limit (varying between about $65,000 and $105,000, depending on the county and number of family members) and purchase price. The program substantially defrays the closing costs that come with purchasing a home, which can pose a serious impediment to buying a home for a young family that has not had the time to accumulate significant savings. WHEDA provides the benefit as a low-interest loan that it recoups by wrapping it into the mortgage it also provides, so the program costs the state nearly nothing.

Of course, any change in the tax treatment of housing would result in some costs for those who already own their homes. These home owners bought their houses under the assumption that they would receive these tax benefits and, perhaps even more important, that any future buyer would also expect these benefits, meaning the owner could effectively add the value of those benefits to the price of the home. This expectation essentially inflates home prices. Changing the tax treatment of home ownership would reduce or eliminate that inflation, but whoever owns a home when the policy is eliminated would suffer all of that loss — raising problems of fairness, let alone of politics.

While the problem of a potential house-price decline cannot be avoided if tax policy is to be changed to better target it toward encouraging ownership, the transition can be smoothed in ways that would help a great deal. The 2005 Tax Reform Panel, for instance, recommended a phased transition from current policy to a tax credit with regional caps based on median home prices. Lowering the limit on deductibility from $1 million to $750,000 could be undertaken immediately with almost no effect on the broader housing market. In subsequent years the cap could be reduced in $100,000 increments until the desired level was reached. Similarly, capping the deduction at 28% immediately would have only a small effect on the broader housing market while a 15% credit is phased in.

Considering the dollar amounts involved, and the fact that a home is easily the single biggest purchase most people ever make, it is worth questioning whether the government should be in the business of encouraging home ownership at all. Typically, the argument in favor of using public funds to encourage ownership is based on the idea that home owners produce some social benefits outside of the benefits they receive themselves. While this idea makes sense in theory, recent evidence amassed by economists through randomized experiments calls this conventional wisdom into question. This work shows that many of the things that are often considered to be positive social benefits of home ownership, like rates of voting and civic engagement, are not actually caused by owning a home.

Furthermore, research shows that owning a home that declines in value makes workers less mobile — a phenomenon known as "housing lock." This is especially apparent when home owners have negative equity, or owe more on their mortgage than they could sell their house for. Certainly the housing bubble and subsequent bust put many recent home buyers in a negative-equity position, and this bust (for obvious reasons) hit especially hard in places that had declining labor markets. Encouraging ownership through public policy exacerbates the problem of housing lock, making it harder for workers to find jobs in other locations by constraining them to a location with a declining labor market.

A gradual transition away from tax policy that encourages home ownership would, of course, yield even greater savings to the taxpayer that could be translated into lower tax rates or other tax benefits, such as additional relief for families. It might also confine government to a more appropriate role.

TARGETING BENEFITS

For far too long, our system of generous tax benefits for home owners has escaped careful scrutiny and criticism. Even in tight fiscal times, when policymakers are eager to find ways to save money, the mortgage-interest deduction and other housing-related tax benefits have remained unthreatened and untouched.

But if the goal of these policies is to increase home-ownership rates in fiscally sensible ways, the current package of housing-related tax expenditures certainly fails. These policies unevenly benefit higher-income residents residing in the suburbs of coastal metropolitan areas — particularly those in California. Instead of encouraging ownership, they tend to make housing cheaper for a small segment of the population that uses those savings to buy larger, more expensive homes than they would otherwise be able to afford.

Reforms that reduce the benefit to upper-income taxpayers and expand coverage to those at the margin between owning a home and renting would increase home ownership while at the same time saving taxpayers a great deal of money. It is time to stop treating these benefits as a third rail of our fiscal politics and to take on some much-needed reforms.