Reclaiming Sovereignty in Financial Regulation

Christmas of 1989 was a good one for me. I had just secured my first adult job as a credit analyst with a community bank in Klein, Texas. Ronald Reagan had left office less than a year earlier. Global communism was imploding. And deregulation was moving forward in multiple American industries — including a banking system that, thanks to decades of technological and financial innovation, was chafing against the rules imposed by the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933.

A decade later, Glass-Steagall would be gutted, ushering in a new era of less-regulated finance that would boom like the California Gold Rush, then collapse into the Great Recession. Like the Great Depression before it, this downturn prompted officials to construct a massive new edifice of financial regulations — one they continue to augment today. But unlike in the Great Depression, many of these new rules are not coming through the political system; instead, they are being imported essentially wholesale from Switzerland and implemented by fiat, thanks to a powerful council that meets a few times each year in the German-speaking city of Basel to make decisions that few Americans hear about and fewer still understand.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS, or simply the Basel Committee) was established in 1974 with a mission to "enhance financial stability by improving the quality of banking supervision worldwide." It has no particular legal authority to do this, but its pronouncements are widely adopted due to the moral suasion cultivated by its entrenched position.

The committee's most ambitious rulemaking, sometimes referred to as the "Basel Process," has come in waves. The reforms of Basel I and II were enacted by most of the world between the 1980s and the early 2000s. The Great Recession marked the beginning of the latest wave of regulations — Basel III — which are meant to prevent similar crises in the future. The final stage of Basel III carries the somewhat unsettling moniker of "endgame" and is set to begin taking effect in the United States in July 2025.

Basel III's endgame consists of 162 pages of compliance documents filled with minutiae just as inscrutable as the securitization strategies that Wall Street's best and brightest developed in the 1990s — strategies that prompted the subprime-mortgage crisis that kicked off the Great Recession. Together with homegrown regulation from the Dodd-Frank Act, it represents an ongoing victory of the large and complex over the small and relatable in matters of finance.

Big Finance fails spectacularly for all to see. Big Regulation fails quietly and insidiously through unintended consequences — like the increasing surrender of national sovereignty to unelected technocrats in Europe. Basel III's endgame deserves as much public scrutiny as the financial behemoths it seeks to tame, but at present is not receiving it. This is one reason why the current regulatory environment is as frightening as the speculative bubbles it means to circumvent. The alternative we need is not blind deregulation, but a vastly simpler and more accountable regulatory apparatus.

BANKING, ANCIENT AND MODERN

The original kings of global finance didn't care about money — at least not at first.

In 1099, the European leaders of the First Crusade wrested Jerusalem from Islamic control. Soon, large numbers of Christian pilgrims from Europe began making the long, dangerous journey to the newly opened Holy Land. The Knights Templar — an elite group of fighting monks — formed to protect the pilgrims on their journey. They made their British headquarters at the Temple Church, which still sits north of the River Thames in central London. Outside the church stands a column topped by two knights sitting astride one horse — said by some to be the Templar's symbol of dedication to a life of poverty.

After a time, the Templars began allowing pilgrims to leave their money at the Temple Church in exchange for a document that would permit them to withdraw an equivalent amount when they arrived in Jerusalem, where the Templars maintained additional locations. It was a neat trick, this cross-country transfer of money — and as the journey from Europe to the Holy Land was long and perilous, it proved quite popular. The success of this and other Templar financial services increased the order's wealth and influence, arguably corrupting its mission and leading to its spectacular downfall in 1312. But the financial seeds the Templars planted ultimately grew into the modern system of international banking.

At its heart, banking today remains a kind of financial sleight of hand — the shuffling of money across space and time. Deposit $10,000 into a checking account, and you might imagine your money is sitting safely in the bank's vault or cash drawers, waiting for you to demand its return or direct it elsewhere by writing a check or making a purchase using a debit card. In the aggregate, of course, this is not true: The banking system contains nowhere near the total value of everyone's deposits in cash. Instead, the bank turns those deposits into not only ideas in the heads of its customers, but also accounting entries — things both immaterial and highly mobile.

Now the sleight of hand can begin in earnest. Your $10,000 can be loaned to a borrower to buy a used car, combined with other depositors' funds to enable the construction of an office building, or simply used to purchase investment assets, such as bonds. All these activities enable the bank to earn an income for its services while spreading people's unused money around like fertilizer to generate real economic growth.

My job as a credit analyst at the community bank in Klein was a great classroom in which to learn about this system, and about how the bricks and mortar of the real economy connect to the financial world of accounting entries. In the 1990s, Klein was booming. New schools, shopping centers, and neighborhoods were sprouting up everywhere. Money followed the rooftops, as the bank's higher-ups liked to say, but also preceded them, as my work taught me. When I wasn't at the bank learning to crunch numbers on a computer, I drove around inspecting houses being assembled by builders who had received construction loans. At each one, I made check marks on a list showing how much had been done since my last visit — the finishing of a frame, the shingling of a roof, the installation of an air-conditioning unit. As I checked more items off my list, more money from the loan would be transferred to the builder's account to fund additional construction. This was the movement of money through time.

Anyone who borrows funds does so in the belief that he will have that much money and more at some point in the future. In exchange for paying interest, the borrower is able to use his expected future funds in the present. But if the expectation proves unfounded, bad things happen. My work inside the bank was meant to preclude that. I pored over the finances of the people and businesses asking for loans, trying to determine if the money they claimed they would have in the future would really be there to pay back the loan. It was part art, part science, and highly imperfect on both the individual and macro levels. On the individual level, a mismatch between present and future money might mean a loan default. On the macro level, it might mean a recession.

This was the genesis of the biggest economic recession of all — the Great Depression.

In the late 1920s, the U.S. stock market reached historic highs. Americans wanted in, regardless of whether they had money to invest. Anecdotes from the era tell of shoeshine boys on Wall Street sharing stock tips with customers. Anyone with $100 to his name might buy $1,000 worth of stock, if only someone would extend him the credit. Margin trading, like any other loan, was based on the belief that the borrower — be it a Wall Street executive or a shoeshine boy — would have the money to pay the loan back in the future. And if stocks kept appreciating as they had been, that was practically a mathematical certainty — or so everyone seemed to think.

Over time, these transactions transformed the market from an orderly investment arena into a veritable pyramid scheme: New money pushing from the bottom was not sufficient to hold up the weight of the entire swollen edifice. Expectations eventually collided with reality, and reality won. On October 24, 1929 — later known as Black Thursday — the market collapsed, unleashing a tsunami of financial ruin across the globe.

A financial bust is often followed by a regulatory boom, and in 1932, federal legislation aimed at shoring up the nation's still-reeling financial system (some 9,000 U.S. banks failed during the Great Depression) became law. The measure was sponsored by Congressman Henry Steagall of Alabama and Senator Carter Glass of Virginia. But it was the Banking Act of 1933 — a more comprehensive bill from the same two sponsors the following year — that would come to be remembered as the Glass-Steagall Act.

Glass-Steagall erected a firewall between the nation's commercial banks and investment markets. It prohibited commercial banks from underwriting or dealing in risky securities, and barred investment banks from taking deposits. It also established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to guarantee individual deposits in commercial banks. This was done in the hopes of discouraging bank runs that could result in bankruptcy and widespread financial panic.

Anyone who has heard George Bailey's inspiring speech to his Building and Loan customers in the 1946 film It's a Wonderful Life knows that the magic of banking requires faith. Even today, it remains the indispensable foundation of the entire system.

TOWER OF BASEL

The same year as Black Thursday, in a seemingly unrelated development, banking representatives from several nations began planning a new kind of international organization, ostensibly dedicated to streamlining Germany's payment of World War I reparations. But the founders of the organization saw their enterprise in grander terms: They believed that in a world divided by national borders, the realm of global finance should have none.

In January 1930, seven nations (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland) signed an international treaty creating the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), which would be governed by the leaders of national central banks and tightly insulated from national politics. The site of Basel, Switzerland, was presumably chosen for its centralized location in Europe and the host nation's famous political neutrality.

Soon afterward, the Nazis would take power in Germany and stop paying World War I reparations, eliminating the BIS's official raison d'être. But the organization was so well constructed for survival that it continued to play a significant role in world affairs.

During World War II, the BIS demonstrated its ability to transcend national politics in service of a seamless financial world, as Adam LeBor recounts in Tower of Basel. At various times, the bank fed intelligence to both the Allies and the Axis powers, and even enabled the Nazis to sell looted gold to fund their war machine. When the war ended, the BIS not only skirted culpability for this activity (with the help of powerful friends like economist John Maynard Keynes and Allen Dulles, a founder of the modern U.S. intelligence system), it also began handling international payments related to the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe. More than that, the BIS had become a forum that many of the world's leading central bankers considered indispensable for privately discussing important issues and coordinating actions.

The United States, for its part, had not signed the treaty creating the BIS and maintained no official presence there. Glass-Steagall appeared to be working as intended during the post-war decades. There was no Second Great Depression.

However, the tides of the business cycle continued to ebb and flow, and periodic financial crises still occurred. One of these involved the 1974 failure of Germany's Herstatt Bank. After World War II, an international agreement known as Bretton Woods specified fixed exchange rates among national currencies: Broadly speaking, each nation maintained a fixed exchange rate against the U.S. dollar, which was itself fixed to the price of gold. But when President Richard Nixon ended the U.S. gold standard in 1971, the rest of the Bretton Woods system fell apart. International currencies started floating against one another, and investors began speculating on their movements.

In the summer of 1974, Herstatt Bank made a large speculative sale of U.S. dollars for Deutsche Marks. When the market moved against this trade, regulators in Germany closed the bank. Because of the time difference between Germany and New York, Herstatt Bank was credited with receiving the Deutsche marks before it had delivered the dollars in exchange. U.S. banks suddenly found themselves in danger of insolvency. The debacle had all the hallmarks of financial contagion, and as part of the international reaction to it, the G-10 — which included the United States — created the Basel Committee.

Tracing the committee's institutional lineage is not difficult. In June 1945, the United Nations was formed to prevent replays of World War II. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) — a lender of last resort to national governments — was created through a pre-charter meeting of the United Nations at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944. In 1962, the IMF convened the G-10 as a source of additional loanable funds. Finally, in 1974, the G-10 created the Basel Committee.

Looking deeper, however, illuminates an even more intimate relationship. The Basel Committee shares digs with an older cousin — the BIS — which both "hosts" the committee and, through its employees, provides it with administrative support. In 1977, the pair moved from the BIS's aged building into a new 20-story modernist tower near a bend of the Rhine River in Basel — a location from which the committee would soon grapple with a new international crisis.

At the time, Latin American nations had been borrowing heavily in international markets to finance their economic development, and by the 1980s, their debts were outstripping their ability to pay. A crisis ensued in which banks were exposed to potentially enormous losses from loans that could not be fully repaid. The Basel Committee responded with the Basel Capital Accord, now known as Basel I: a set of rules adopted in 1988 to ensure the world's banks maintained sufficient capital to withstand crises.

Basel I required that banks maintain a minimum capital of 8% of their assets. But since all assets are not created equal in terms of risk, much of Basel I was concerned with weighting different types of credit-based assets to create a common standard against which to apply the 8% calculation. U.S. government bonds, for instance, were considered so safe that they were assigned a weighting of zero, meaning banks didn't have to hold any capital against them. Riskier assets, such as business loans, received a heavier weighting against which to apply the 8% rule.

It sounds simple enough. But Basel I was periodically amended, and as always, the devil emerged in the details. One new ruling was meant to address "the effects of bilateral netting of banks' credit exposures in derivative products" and "to expand the matrix of add-on factors." An amendment a year later changed this from a bilateral to "multilateral" netting. After that, the Basel Committee worked with securities regulators to incorporate risks from non-credit-based assets, such as foreign currencies, commodities, and stocks. As the Basel Committee website claims, its rules were always "intended to evolve over time." Like its host, the BIS, the Basel Committee was playing the long game.

AN ERA OF DEREGULATION

By 1992, I was working at Commonwealth United Mortgage in Houston, where I first learned that a bank could bundle home loans together like a cord of firewood and sell them into a secondary market through a process known as "securitization." Commonwealth United Mortgage was itself a bundling of two different companies that had recently merged. As banks increasingly securitized their loans, the U.S. banking industry consolidated; everything was becoming bigger. Then in 1994, Congress passed the Riegle-Neal Act, permitting bank branches to cross state lines and thereby accelerating consolidation. Throughout the '90s, banks' profits snowballed — as did the stock market during the tech boom later that decade.

As in all speculative frenzies, confidence in endless appreciation became endemic, and deregulation continued apace. For years, Glass-Steagall's regulations had been loosening by way of agency and judicial interpretation. Meanwhile, banking itself was changing on a molecular level. Fewer and fewer families held their savings in traditional bank accounts; instead, they tended to favor newer instruments, such as mutual funds. And in 1999, the Glass-Steagall Act was partially repealed by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act. For the first time since the Great Depression, commercial banks and securities firms could have overlapping employees and management, and the former could become more involved in underwriting securities.

Rightly or wrongly, popular wisdom came to associate this change with all the trouble that followed. In the early years of the 21st century, home values rose higher and higher as lending standards fell, thanks in part to the federal government's goal of increasing home ownership among low-income households. The government guaranteed low-income mortgages through the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), which were generally securitized and resold into the secondary market. This fed a frenzy in which increasing numbers of individuals purchased homes as investment vehicles rather than places to live. As with the stock market in 1929, the continuance of the cycle depended on prices rising forever — an impossible scenario.

Around this same time, a self-congratulatory sentiment emerged in the field of economics. Economists believed that the business cycle and its requisite ills had been, if not mastered, at least domesticated by a potent combination of neoclassical economic theory, deregulation, and the skilled practice of monetary policy by people such as Alan Greenspan — whose tenure at the helm of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006 included the second-longest period of sustained economic growth in the United States on record: the decade from 1991 to 2001. He retired from the Federal Reserve to accolades that included Senator John McCain's call for him to keep serving his country, even if it meant propping up his lifeless body in sunglasses, Weekend at Bernie's style.

Meanwhile, a different kind of hubris was developing in Switzerland, where the Basel Committee had released a new framework for capital requirements — Basel II — after working on it for some six years. The comprehensive document is 347 pages, containing sections such as "Operational requirements for synthetic securitisations" and "Overview of Methodologies for the Capital Treatment of Transactions Secured by Financial Collateral under the Standardised and IRB Approaches." A page-and-a-half near the front is devoted solely to defining acronyms. Banking — the neat trick invented by the Knights Templar — had grown into a bewildering mass of complexity comprehensible only to an initiated elite. In this game, regulators created new rules, profit seekers created new strategies to exploit them, and the opportunities for unintended consequences multiplied like the adverse effects of mixing prescription medications.

A REGULATORY BIG BANG

The reckoning began with the deflation of the U.S. housing bubble. By this time, my career had taken an unusual turn for an economics major: I had become a freelance writer. But most of my clients were still in the financial field, and in 2008, one of these — an independent wealth manager in Fort Worth — related a disturbing experience he'd had on a trip to New York to meet with representatives of Goldman Sachs.

U.S. credit had been tight for months as the subprime-mortgage crisis spread. But this was something of a different order. The financial giant Lehman Brothers had filed for bankruptcy, and credit markets were seizing up in a way no one could remember seeing before. The Goldman Sachs representatives had shown him what was happening on a computer monitor, but this was simply a modern representation of a very old-fashioned problem: Confidence in the financial system had shattered, and everyone was holding onto their liquidity as tightly as they could.

These signs portended an economic Armageddon. They soon monopolized the news cycle. The federal government stepped in to bail out firms deemed "too big to fail," such as the finance and insurance conglomerate American International Group (AIG). And with that, the era of deregulation came to an end.

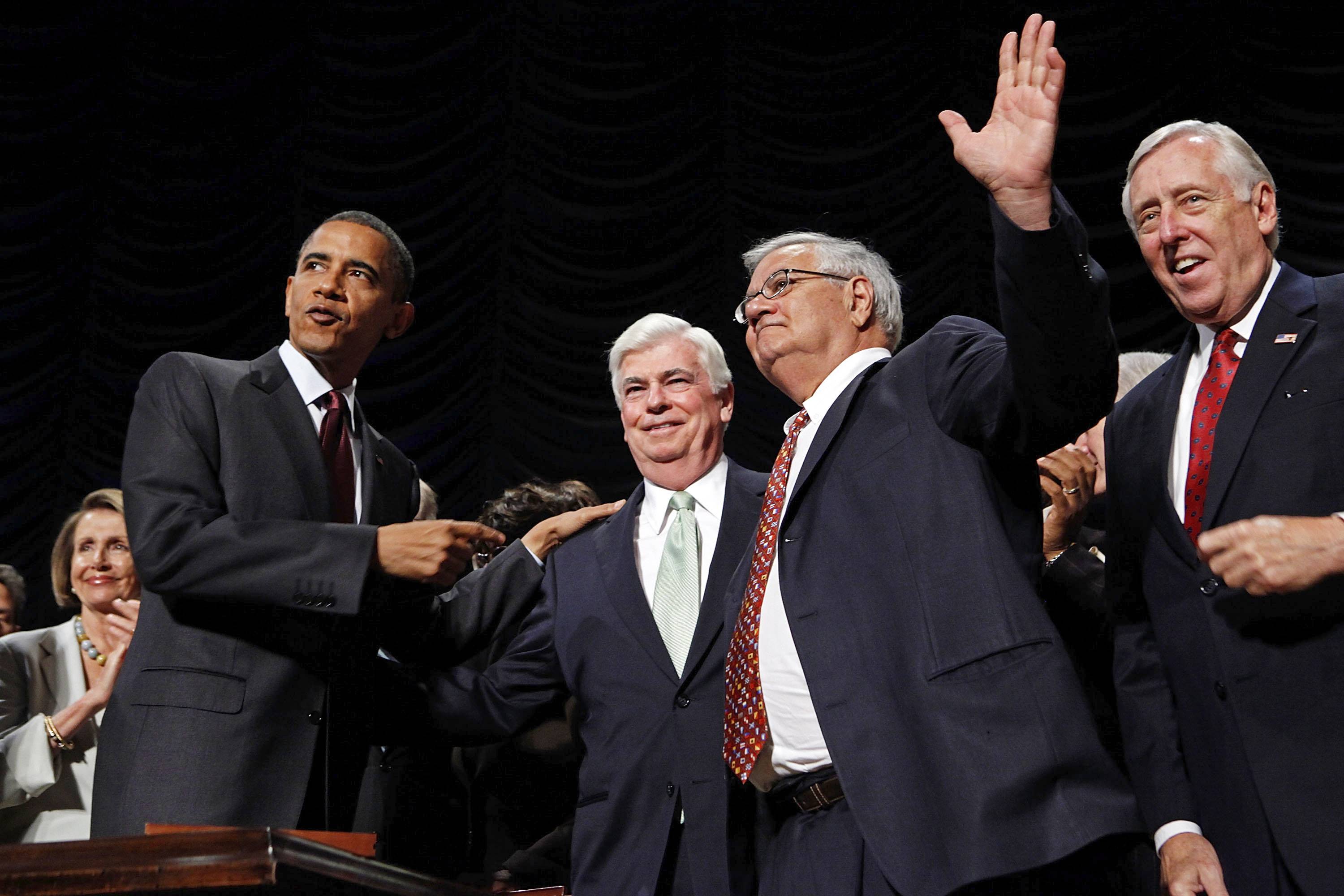

Reregulating the system began relatively quickly, in the form of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. Within its 850 pages of rules (not counting the thousands more written by regulatory agencies post-passage), there existed something popularly known as the Volcker Rule. Paul Volcker, the Federal Reserve president widely credited with ending spiraling inflation in the early 1980s, had been appointed by President Barack Obama to lead an advisory board on recovering from the Great Recession. The rule he argued for was to prohibit commercial banks from "proprietary" trading (trading for their own profit) in risky assets such as stocks and derivatives, as well as from managing hedge funds and private-equity firms. Many saw it as a rule in the spirit of Glass-Steagall — simple, direct, and decisive.

Not to be outdone by U.S. legislative action, the Basel Committee in Switzerland issued an ambitious new global accord: Basel III. It sought to build liquidity in the global financial system by significantly raising the amount of capital that the largest banks must hold against their risk-weighted assets. It also sought to force everyone onto the same page by reducing banks' ability to use their own internal models to determine assets' riskiness. The committee has released supplemental rules since then, including those covering the so-called endgame that will take effect in the United States in 2025.

Back in the United States, in July 2023, the Department of the Treasury, the Federal Reserve System, and the FDIC jointly issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking related to Basel III's endgame, along with an invitation for public comment. The notice consists of 316 pages in very small type for a total of over 290,000 words — exceeding the New Testament by more than 100,000 words. Included are mathematical formulas that would feel right at home in an economics Ph.D. dissertation. Even after working in the financial field for 30 years and earning a master's degree in economic research with a finance minor, the details of such regulatory pronouncements from Basel — absent perhaps a year to devote exclusively to their study — are beyond my understanding.

Below all the complexity, faith remains the foundation of the entire system. But how does one have faith in something so inscrutable, aside from placing it blindly in the experts who write the rules?

For many, including myself, this is a heavy lift. Regulatory technocrats are just as prone to hubris and overreach as the financial wizards behind the subprime-mortgage crisis. And while their failures might be less visible, they are just as real.

Many critics say the Basel III regulations are raising borrowing costs and tightening credit, which restricts economic growth. Supporters might argue that this is the price we must pay to filter risk from the system. But in a paper hosted on the Columbia Business School's Jerome A. Chazen Institute for Global Business website, Jing Wen finds evidence that Basel III has increased rather than decreased risk-taking by borrowers — the kind of unintended consequence researchers love to uncover (and regulators presumably hate to learn of).

In the end, if the choice is between an unregulated market that punishes investor mistakes through cyclical disturbances and a regulatory apparatus that tries to impose stability at unknown cost by spiraling rules into ever-greater impenetrability, I would choose the former. But there may be a middle-ground option.

The fan club of the text of the Volcker Rule that appeared in the final Dodd-Frank legislation does not include Paul Volcker. The year after its passage, the New York Times quoted his remarks about the rule's final text, which took up 298 pages of Dodd-Frank: "I don't like it, but there it is....I'd write a much simpler bill."

He wasn't the only person decrying the bill's complexity. In the wake of Dodd-Frank, I interviewed the president of a small community bank in Stamps, Arkansas, that was struggling to decode and comply with the mess of new rules. It taught me a lesson about what happens when regulations meet reality. This small-town banker was a real-life George Bailey, but instead of standing up to the snarling visage of Mr. Potter, he was feeling the heat from an army of faceless lobbyists and technocrats in Washington, D.C. Their rulings were just as convoluted as those out of Basel, especially to a bank that lacked, as the president informed me, a staff of lawyers and certified public accountants to work on compliance issues.

Although his organization was much smaller than the community bank where I had worked out of college, its survival was arguably more important: It was the only bank the town had left. The same regulations that were designed to standardize and police the behavior of Wall Street giants were making it hard for this smaller institution to profitably offer deposit accounts and loans to its community. In an era of consolidation, mergers, and a general trend toward bigness, I was startled when the president told me that his bank, which had been around since 1903, might soon need to shrink to survive. It only had 13 employees at the time.

THE PATH TO SIMPLICITY

Like the regulations of the committee it hosts, the BIS itself has continued to grow, and today it employs some 600 individuals. The United States assumed formal membership in 1994, with the Federal Reserve chair and the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York taking seats on the board. As for the powerful committee the BIS hosts — the Basel Committee — it admitted new members in 2009 and 2014 and, according to its website, is now made up of "45 members compris[ing] central banks and bank supervisors from 28 jurisdictions."

Given trends such as these, what are the prospects for more simplicity in financial regulation? Can we hope for rules that are comprehensible to an intelligent but non-expert electorate? Glass-Steagall was easy enough to understand: Commercial banks shall not be investment banks, and vice versa. So was Bretton Woods: Each national currency shall be pegged to the dollar, and the dollar to gold. The Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 — which the Riegle-Neal Act repealed in 1994 — was even more basic: Banks shall not cross state lines.

Attempting to turn back the clock on legislation is unlikely to succeed. But voters can demand a return to simpler financial regulation. In effect, they would be asserting their own relevance to the process. A crusade against complexity might even generate interest among both Republicans and Democrats.

One model for legislative change, buried like a diamond inside Representative Jeb Hensarling's failed 2017 Financial CHOICE Act, is a provision called an "off-ramp." It would have allowed institutions that voluntarily held additional capital to simply opt out of much of Dodd-Frank and Basel III. But the CHOICE Act did not pass, thanks in part to opposition from big banks, for whom being able to decipher complex regulation creates a competitive advantage over small upstarts. One wonders if a stand-alone off-ramp bill might stand a better chance of passage.

In another potential path to change, the regulatory community itself might be beginning to acknowledge its complexity problem. In the United States, the appearance of the latest Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for Basel III has generated more pushback than expected. Charles Taylor, who was the deputy comptroller for capital and regulatory policy at the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency from 2011 to 2015 and served as a representative to the Basel Committee during Basel III negotiations, told me that Basel III's framework is showing its age.

According to Taylor, when the first version of the regulations came out 50 years ago, it focused on assets and the associated credit risk at the level of individual institutions. In successive versions, it expanded its reach to take account of market, liquidity, operational, and other risks. The result is a focus on risk-weighted assets as the key variable through which to regulate the system — a variable that Taylor described as "a kludgy idea the day it was dreamt up." In practice, adjusting and patching this framework has created more complexity over time. Taylor put it this way:

The thing that is hard to disentangle is what is chicken and what is egg. Was it the regulations getting complicated that provoked the banks to develop complicated structures and instruments, or was it the ingenuity of financial innovation that forced the regulators to develop more-complicated approaches? For sure, increasing complexity on one side has spurred increasing complexity on the other, time and again.

He added that there are other ways to approach financial regulation that might lower compliance costs, such as replacing risk-weighted assets with income as the key variable. Additionally, starting with systemic rather than institution-level risks might offer opportunities for not only a better regulatory framework, but also a simpler one. The regulatory community has talked about such approaches, but has failed to thoroughly investigate them. Taylor said that a pause in ratcheting up complexity might make sense: It would allow regulators to "take a good hard fundamental look at the whole thing."

IN THE PEOPLE'S HANDS

Something tells me that even unelected regulators half-a-world away can feel pressure from an electorate. A political push for simpler financial regulation could change not only rules enacted in the United States, but those coming from Basel as well.

In January 2024, the top floor of the BIS tower hosted an unveiling of competing design proposals for converting its headquarters site "from building to campus," as its website says. This will involve tearing down four "ageing and inefficient buildings" that stand near the tower. Judging from photos and Google Earth, these buildings are quaintly attractive, and stand at most a third of the height of the tower. The architectural clash is indeed striking, and I doubt the buildings stand much chance of being preserved. But as with regulations, there are alternative possibilities for what will replace them. Hopefully the BIS's design committee, and America's voters, will make the right choice.