Party Factions and American Politics

We seem to be living in a period of "creedal passion" — the late political scientist Samuel Huntington's term for the moralizing suspicion of our political institutions that grips the United States every 60 or so years. According to Huntington, our founding principles of liberty and equality can never be fully realized, which creates a persistent gap between our ideals and our institutions. Periodically, this gap spurs Americans to reform our institutions so that they conform more closely to our ideals — to somehow bring the "is" and the "ought" closer together.

Today, the intensity of creedal passions on the left and right has led some observers to warn that American democracy is at risk. Others argue that the crisis is not one of American liberal democracy per se, but rather one of the nation's political parties. Our parties, the argument goes, are no longer playing their essential mediating role between citizens and government, fostering a considerable disconnect between representatives and the represented.

The political dysfunction we can all see has sparked a resurgence of interest in party reform. Some want to decentralize our parties in favor of a multi-party system; others want to make our two parties stronger and more hierarchical. Short of a major change in our political system, however, we need to find a way to work within the one we have.

The good news is that, over the last century and a half, intra-party factions have accomplished many of the goals reformers hoped to achieve — and they might do so again. In fact, such factions have played a significant but largely unrecognized role in shaping American politics since at least the Civil War.

Focusing more narrowly on intra-party factions rather than on parties as a whole sheds new light on the American party system, offering us a distinct way of thinking about party reform. Difficult as it will be in our polarized and closely competitive political environment, forging factions oriented toward practical, as opposed to ideological, governance is arguably the best way to add a dimension of substantive diversity to our two-party system while increasing the strength of the parties as governing instruments. Such factions may reduce party unity, but paradoxically they may also increase the parties' ability to govern. They hold the key to helping us muddle through our moment of creedal passion.

PARTY SYSTEMS

Grasping the value of intra-party factions and assessing the various reform proposals on the table requires something of a running start, beginning with an overview of the range of party systems available. The lesson to be drawn is that every party system has its advantages and disadvantages. Reformers would be wise to keep them in mind.

Political scientists have extensively debated how to classify party systems in democracies. While there is much variation, our analysis can begin with four basic models.

The first is the Westminster model, which originated in England and is characterized by single-member districts, first-past-the-post elections, and the delegation of power from members of parliament to party leadership. In this system, the parties campaign in competitive elections on clear platforms written by party leaders who have the power to enact those platforms into law if they emerge victorious. The result is two large, strong parties that voters can more easily identify as responsible for any given policy change.

Another model provides two sizable but weak parties. America offers the paradigmatic case, and, despite frequent comparisons of the two-party systems in the United States and United Kingdom, ours has more in common with its imitators in Latin America than it does with the Westminster model.

The American party system includes a nationally elected executive and a federal legislature made up of representatives from single-member districts chosen through first-past-the-post elections. This arrangement incentivizes the creation of two large, undisciplined parties with limited capacity to enact their programs. The upshot is that party members must negotiate across the aisle to pass legislation that does not resemble the parties' official platforms. Though voters may have difficulty assigning praise or blame to either party for any particular policy in such a system, the policies enacted typically — and often by necessity — represent some measure of compromise, and sometimes a broad consensus.

The third system is the proportional-representation (PR) model, which is most commonly found in continental Europe and is characterized by the presence of multiple parties. (Some refer to it as the "multi-party" model for this very reason.) In such systems, voters select from among various smaller parties with platforms that more closely approximate their policy preferences. Typically no single party wins enough seats in parliament to make up a majority on its own, so the parties are forced to form coalitions to select a prime minister and other ministers that form the government.

The fourth model, typified by Germany, combines elements of the Westminster and PR systems. Some seats in the Bundestag are selected by proportional lists, while others are chosen by single-member districts. As a result, Germany is able to draw on the strength of two-party systems created by single-member districts while also receiving the participatory benefits that come with multi-party proportional lists. The larger parties are strong enough to govern, while the smaller parties give voice to a range of societal interests.

THE BEST PARTY SYSTEM?

For most of the 20th century, American political scientists held up the Westminster model as the best party system available. In their minds, Britain's hierarchical parties yielded the most civilized politics and the best public policy one could hope for. In 1950, the American Political Science Association issued a report calling for American parties to become more "responsible," by which it meant more like British parties. Even today, Yale University political scientists Ian Shapiro and Frances McCall Rosenbluth argue in their book Responsible Parties that systems modeled on the Westminster system remain the best available. "Parties that are broad-gauged, encompass an electoral majority, and [are] disciplined enough to enforce majority-enhancing deals," they conclude, "are as good as we can get in a democracy."

The two qualities that proponents of the Westminster model appreciate are party size and strength. Parties will be large when only two of them cover almost all of society. They will be strong when they have enough discipline to run campaigns on policy platforms and enact those policies when they win a majority of the vote. Strong parties are also capable of punishing or expelling dissidents. When it is clear which party is in charge, which policies it favors, and which party enacts a given policy, the public can easily hold the party in power accountable by either reelecting its members or throwing them out in favor of the opposition party.

From this perspective, the problem with other party systems is that they lack parties with either sufficient size, strength, or both. In PR systems, for instance, voters can choose from a wide array of smaller parties with narrow or even single-issue policy programs, allowing them to make voting decisions that more closely reflect their policy preferences. Voters may thus attain the satisfaction of selecting candidates or parties they truly favor. However, they will also have little sense of the coalition the parties will develop after the election or what mix of policies the governing coalition will enact. This makes it difficult for voters to praise or blame any particular party for a given policy outcome.

PR systems also tend to be plagued by instability, as party coalitions can be hard to forge and sustain. Consider the difficulties that Belgium, Spain, Israel, and other countries with PR systems have encountered while attempting to form governments in the 21st century alone. Nor have such countries been immune to populist, nationalist, or anti-immigration parties roiling their politics in the last two decades — Italy, France, Greece, Spain, and Austria are all cases in point.

Modern Germany is the example on which many contemporary proponents of PR systems rest their case. The German system provides the stability and responsibility of two large parties as well as the electoral outlet inherent to smaller parties. The results are impressive, making the German model the current leader in the contest for the best party system.

But the German model has proved hard to replicate elsewhere, and it has recently shown signs of strain. The elections of 2017 and 2021 offer glimpses of a future where a large slice of the working class — under pressure from globalization, declining unions, and immigration — seeks out radical alternatives and destabilizes the major parties. Big shifts in voting patterns, the third-place finish of the nationalist Alternative for Germany Party in 2017, and drawn-out negotiations after each election suggest that an important portion of the electorate is already looking for options outside the major centrist parties. Such flux may portend instability.

OUR TWO BIG PARTIES

The United States clearly doesn't lack for two major parties. The problem, depending on the analyst one asks, is that they are either too strong or too weak along some important dimensions.

For those who see America's parties as too strong, the problem resides in the recent development of ideologically sorted, highly competitive parties that contest elections on divisive issues that preclude compromise. Scholars who favor this thesis argue that the pattern whereby members of Congress now regularly vote along party lines, coupled with the majority party's ability to control the policy agenda in each house of Congress, reflects greater party strength. Evidence of strength can also be found among voters. Emory University political scientist Alan Abramowitz, for example, has found that a small percentage of party identifiers in the electorate is more intensely partisan than in the past, and that "affective partisanship" — an intense dislike of the other party — has grown in recent years. Another group of scholars argues that although the parties' informal networks of elites have, in theory, handed over key decisions to primary voters, they retain control over presidential nominations. (This claim in particular came under intense scrutiny with Donald Trump's victory in the 2016 Republican nominating contest.)

Critics of the strong-parties thesis argue that the features outlined above tend to mask profound institutional weaknesses. For instance, American parties typically fail to enact most of their favored policies, even if they win a majority in both houses of Congress. The reasons for this lie largely in America's constitutional design, which consists of staggered electoral cycles, federalism, bicameralism, and an independently elected president. Such a system tends to foil the concentration of political power, but it also produces weak governing parties.

Indeed, if the test of party strength is its ability to pass legislation, American parties are remarkably anemic. As James Curry and Frances Lee point out in The Limits of Party, most laws must receive bipartisan support to pass in today's environment, meaning the final products — which are the result of significant negotiation and compromise — rarely reflect a party program that either the president or congressional leadership campaigned on. This makes apportioning praise or blame for government action (when there is action) a difficult task.

As a consequence, party unity today is more about political messaging than legislating. Given the relatively slim and unstable majorities in either chamber of Congress over the last 25 years, every election cycle holds out the false hope that, by vigorously opposing everything the other party does, one's own party will someday run the table and be able to enact its policy program. The result is higher party-unity scores — along with legislative gridlock.

Other attributes of American parties contribute to their relative weakness. For instance, party organizations cannot discipline their members by, say, refusing to renominate dissident members of Congress. Nor can they enforce coordinated messaging in campaigns. As a result, individual party candidates are free to develop messages and policy positions tailored to their districts or states. And once they enter Congress, they can refuse to vote with their party without paying much of a price.

Several changes to that system have abetted the weakness of American political parties in recent decades. State and local party organizations, which once furnished the parties' organizational strength, have largely disappeared. Primary voters, rather than party organizations, now determine which candidates receive a party's nomination. As a consequence, candidates tend to run their own campaign organizations with only modest assistance from the parties. At the same time, the millions of dollars spent during elections tend to flow not through party institutions, but through outside groups.

In sum, on a few measures of party strength — namely party-line voting in Congress and majority-party control of the legislative agenda — America's parties appear strong. But in terms of the dimensions used to gauge the strength of the Westminster model — namely platform discipline among candidates, a mechanism for punishing party dissidents, and, above all, the ability to enact a party platform — our parties look relatively weak. When these factors are combined with party organizations' impotence, the oversized influence of outside groups on campaign funding, and the electorate's relative inability to hold party members accountable for the policies enacted, their frailty becomes all the more apparent.

PARTY REFORM

Given the pathologies of our current party system, interest in institutional restructuring has surged. Today, there are two basic approaches to party reform.

The first — premised on the impression that our parties are too strong — is to weaken the parties by disaggregating them in favor of a multi-party system. Lee Drutman of New America favors adopting a multi-party system similar to that which prevails in Europe. He sees such countries' systems as vastly superior to our own. In Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop, he writes:

Multiparty democracies are more stable. They are more responsive. They represent diverse interests better. Economic inequality is lower. Parties are stronger. Voter turnout is higher. Compromise is more valued. Citizens who live in them are happier, and more satisfied with the state of democracy.

The way such a regime could be achieved on this side of the Atlantic, Drutman contends, is through the widespread adoption of ranked-choice voting (RCV) and the establishment of multi-member districts for many offices. Drutman also favors a dramatic increase in the size of the House of Representatives — from its current 435 members to a total of 700 — which would reduce the average size of congressional districts from 760,000 to 470,000 voters. Such a combination of reforms would create a simulacrum of proportional representation.

Not all reformers of this stripe are as radical as Drutman; others suggest a variety of smaller changes to our voting, election, and campaign-finance systems that would alter party competition. But the general aim of these proposals is to weaken the parties, ostensibly giving more power back to the people.

The second thrust of reform thinking pushes in favor of two stronger, more disciplined parties. Jonathan Rauch of the Brookings Institution, for instance, suggests that we lift restrictions on party coordination during campaigns, repeal limitations on campaign finance that drive money to outside groups, and require candidates to obtain petition signatures from elected or county-party officials. The aim of such proposals is to endow parties with greater power to select their own nominees, control campaign resources, and ultimately discipline their members once they're in office.

While proponents of strengthening the parties have correctly identified party weakness as the root of our system's predicament, the prospects for Rauch's neo-Westminster system appear dim. Opponents will be quick to characterize efforts to make the parties more hierarchical as elitist, undemocratic, and a way to hand the keys over to special interests and the wealthy. Drutman's multi-party utopia is even less likely to become reality — and, in any case, it misdiagnoses what ails our current system. More modest proposals that seek to strengthen parties as mediating institutions offer both a more effective and a more realistic way to proceed.

PARTY FACTIONS

In lowering their sights, institutional reformers might try to find ways to encourage the cultivation of factions that push in the direction of practical governing and legislating. Rather than attempting to overhaul major elements of our existing system — a challenging task in any political climate — such a strategy would look to combine the cohesion and discipline of a Westminster model with the diversity of the PR model, all while working within the confines of the system we have.

Because America's two major parties lack the tools to enforce much discipline, groups consisting of lawmakers, activists, pressure groups, and intellectuals often emerge beneath the party labels. These intra-party factions are defined by a degree of ideological consistency, organizational capacity, and temporal durability. They take a stand, develop new ideas, refine them into policies, promote them in the public square, and push them forward at the governing level. In doing so, they shape the major parties' political and ideological positioning. In our history, if the parties have sometimes lacked purpose, factions have often provided it. Indeed, factions can be more influential than the parties as wholes in setting the government's agenda. Focusing on factions, rather than revamping the entire party system, holds out the most realistic prospect for improving our politics.

That said, the term "faction" has a negative connotation in the United States. In Federalist No. 10, James Madison famously called for institutions to "break and control the violence of faction," which he defined as "a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community." But factions can also be thought of in more benign terms — as "parties within parties" that imbue America's two-party system with an almost multi-party dimension at the governing level.

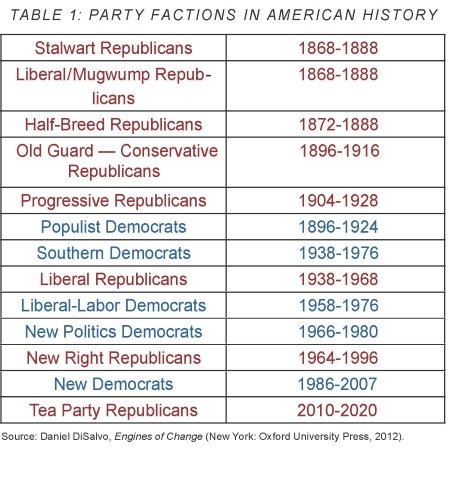

In Engines of Change, I identified 12 major factions that have arisen in America between the Civil War and 2010, including the Stalwart Republicans in the 1870s and 1880s, the Progressive Republicans in the first quarter of the 20th century, the Southern Democrats at mid-century, and the New Democrats in the 1990s. University of Oklahoma political scientist Rachel Blum has made a compelling case that the Tea Party, which emerged in 2010, should be added to this list. All told, at least one faction has been present within one of America's two parties for most of the last 150 years.

In many of these cases, the factions sought to take over their host party and recast it in their own image. Consider the Tea Party's strategy, which was to challenge incumbent Republicans in primary elections at all levels of government. Over time, the mere prospect of being "primaried" by a Tea Party candidate was sufficient to alter incumbent behavior in ways favorable to the faction. And once in Congress, the Tea Party faction's representatives formed a series of caucuses to magnify their influence on legislation. Whether the Tea Party took over the GOP and paved the way for a Trump faction or receded as Trump emerged is the subject of ongoing debate.

On the other side of the aisle, Democrats have witnessed the emergence of a potent progressive faction that has reshaped that party's public image in fairly short order. Senator Bernie Sanders's presidential campaigns and the "Squad" in Congress have provided the public face of this faction, from which slogans such as "Medicare for All" and the "Green New Deal" have issued. While it is unclear how much of the rest of the Democratic Party subscribes to this faction's views or how organizationally coherent it really is, little organized opposition to it has emerged.

Still, over the last few years, factions in both parties have had trouble fundamentally altering patterns of congressional voting behavior. This suggests that no faction has acted as a real broker within its own party or with members of the other party. But that could change in the not-too-distant future.

FACTIONS AND POLARIZATION

Factions are a double-edged sword: They can provoke partisan rancor, but they can also mitigate partisan discord. The trouble with recent factions is that they have abetted polarization, increased affective partisanship, and made governing arduous for members. At the same time, party polarization has made it more difficult for policy-oriented intra-party factions to form. But the emergence of such factions is increasingly necessary for even modest legislative progress.

Over the last two decades, our two major parties have learned that they can exercise a modicum of power without forming a stable majority coalition, which reduces their incentives to take steps to form such a majority or develop a serious governing agenda. As a result, we lack factions with governing priorities, and both parties have proven themselves poor governing instruments in the 21st century.

By casting a glance back at American history, however, we can see that factions that seek to move their party toward the median voter are possible — and not just when their party is in the minority. Recall that not long ago, some frustrated Democrats created the Democratic Leadership Council and attendant organizations to promote the New Democrats as a distinct brand within the party. A congressional organization soon followed. Within little more than a decade, the New Democrats could boast of electing and reelecting one of their own as president and enacting a string of policy measures.

Some research suggests that effective factional organization can alter lawmakers' behavior. University of Chicago political scientist Ruth Bloch Rubin studied 19 intra-party congressional organizations from 1908 to 2014 and found evidence that they can influence legislators' policy preferences through persuasion and collaboration. This conclusion makes intuitive sense: Members of Congress do not always arrive in Washington with fixed positions dictated by their constituencies on every issue, meaning their views on certain issues can be reshaped by intra-party organizations on Capitol Hill.

Looking ahead, political scientists Steven Teles and Robert Saldin have sketched in these pages what governing factions might look like in the future. Longer-term factionalism might, as Teles and Saldin suggest, encourage the formation of intra-party coalitions that can draw voters away from the two major, highly polarized parties. Electoral competition could remain close, control of institutions could continue to seesaw, and polarization may well persist, but over time the larger party system might well bend toward more moderate, practical governance.

By facilitating the creation of governing-oriented factions to help formalize debate within the parties, this strategy offers a way for Americans to reap some of the benefits of a multi-party system without overhauling our electoral institutions. Though such systems require extensive negotiations between parties to forge a governing coalition, in the American system, that process would be contained within the envelope of our two-party structure. The idea here is not to empower "moderates" or "centrists" per se, but to allow for lawmakers to hammer out policy solutions in a constructive manner — which could help ease congressional gridlock and increase the likelihood that each party will achieve some of its legislative goals.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Of course, in an era hostile to governing factions, anyone determined to pursue this strategy will have to confront a series of challenges. The first, as noted above, is the fact that neither party has suffered a series of dramatic electoral losses in recent decades — the sternest teacher in a democracy and the outcome most likely to provoke a change in party behavior. The second is determining how to cope with the unmediated circulation of information — some of it poor or false information — that gives a strong advantage to radical activists in both parties. A third is the fact that the parties' poor performance often leads to calls to weaken the parties further, which will only aggravate the troubles afflicting our system.

Yet since neither party is genuinely winning in the current party system, polarizing strategies may be reaching their limits. This means there is real potential for a party faction to reap the benefits of moving first. While institutional overhauls are probably too heavy a lift, it may be possible to provide the space for governing factions to develop through more modest reforms.

At the electoral level, switching to a RCV system during party primaries might make it easier for factions to form by allowing more granular representation of the various intra-party interests. Revisions to the redistricting process might also help encourage factions to develop. For instance, if districts were drawn with an eye toward reflecting the diversity of public views in a given region (at least as far as state demographics allow), they might help elect a cohort of legislators that are less beholden to particular constituencies — and thus more free to negotiate across party lines.

In government, reformers can focus on decentralizing authority in both houses of Congress. Loosening the grip of party leaders over rank-and-file members frees the latter to sort themselves into smaller, more varied factions that reflect certain governing values, interests, and priorities — much the way parties in a multi-party system operate. These factions could then work with other factions — either those within their party or those from across the aisle — to hash out differences, negotiate, and ultimately push an agenda forward.

Such ideas, or some combination of them, would not offer a cure-all for what ails our body politic. But over time, they might enable the two parties to campaign on more substantive, practical matters, and to govern with the diverse values and interests that make up our pluralistic society in mind.

FIRST STEPS

New ways of thinking to assist dedicated activists, donors, and elected officials in creating new factions will certainly be necessary, but there may be more openings than the conventional wisdom suggests. The first step will involve reassessing some of what many now consider insurmountable barriers to the development of intra-party factions.

Consider ideology. While it is common to hear that the parties are more ideologically divided than ever before, there are reasons for skepticism about such claims. Ideological distance between members of Congress as measured by political scientists is inferred from roll-call voting behavior. But the extent to which roll-call voting patterns capture members' substantive policy positions is debatable.

One problem is that it is very hard to distinguish ideology from partisan loyalty as the driver of voting behavior. To calculate ideological distance between members, one must assume that all votes are sincere — i.e., that before casting a vote, a member of Congress looks at each item and determines how far the measure is from his ideal policy point. If some members' votes represent efforts to enhance the party brand or burnish their own political images, or simply to support their own party as a default position, then measures of ideological distance lose their precision.

In addition, as political scientist Verlan Lewis has shown, the policy agenda at any given time is changing, which complicates our understanding of party ideologies and renders unpersuasive the hackneyed claim that conservatives have moved far to the right and liberals only a little to the left (a thesis known as "asymmetric polarization"). Charles Blahous and Robert Graboyes of the Mercatus Center point out that the claim is the product of the illusion produced by the leftward movement of the political center of the overall domestic economic- and social-policy agenda. Consequently, they could not find a single issue area where the GOP had moved further to the "right" than where the party stood in 1980 or 1996; all the Republican shifts were to the left of where the party was previously positioned. Judge Glock of the Cicero Institute recently made a similar case in these pages.

If members' substantive policy positions are actually closer than many believe, there may be more room for intra-party governing factions to form, reach across the aisle, and flourish. It may be that the parties are not as far apart as many assume, but that politics has become more combative when party control of governing institutions appears to be up for grabs every election cycle. Combine that observation with partisan sorting (e.g., the disappearance of pro-life Democrats, Rockefeller Republicans, and the like), and it becomes apparent that American politics has become much more belligerent without becoming much more ideologically divided. If that is in fact the case, factions might help us find ways to break through the impasse and assist each party in securing policy wins.

INCREMENTAL REFORM

Reformers' hopes should be modest, and not only because they are divided. There have only been four examples of major electoral reform in American history: the Whigs' institution of single-member districts for House elections in 1842; the adoption of the 17th Amendment, which provided for the direct election of senators, in 1912; the Warren Court decisions that applied the idea of one person, one vote to legislative bodies and made districts more proportional in size; and the implementation of primaries as the principle way of selecting presidential candidates by the Democratic Party in 1972. Outside these examples, party and electoral reforms have been driven primarily by small, incremental changes.

Reformers should also bear in mind that the performance of party systems is influenced by countless factors, from constitutional structure to economic growth. Nearly all party systems appear reasonably effective when the economy is humming along and prosperity is widely dispersed. If the U.S. economy had performed the way it did in the 1990s for the preceding decade and a half, it would be difficult to imagine Trump's election in 2016. Similarly, it is hard to imagine the surge of populist parties in Europe without the decline of unions and steady manufacturing employment.

The goal for any system should be to achieve a measure of healthy competition and government accountability. Short of a revolution, we must work within the system in which we find ourselves. Discovering new ways to forge factions dedicated to good public policy — rather than exacerbating polarization or changing the entire political system — offers our best bet.