Our Evolving Immigration Policy

For all the debate that surrounds America's immigration policy, just who is responsible for enforcing that policy has rarely been in dispute in recent decades — until Arizona adopted the statute S.B. 1070. Arguing that the federal government had proved incapable of stopping the illegal immigration wreaking havoc in the state, Arizona lawmakers took matters into their own hands, enacting legislation that used state penalties and state police to try to give meaningful force to federal laws already on the books. Washington, for its part, resisted, claiming that Arizona's approach intruded on federal prerogatives. The federal-state power struggle ultimately landed before the Supreme Court, which, amid a swirl of politicized commentary on both sides of the matter, issued its ruling in June.

"The Government of the United States has broad, undoubted power over the subject of immigration and the status of aliens....The federal power to determine immigration policy is well settled," opined Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the Court's majority in Arizona v. United States. In a 5-3 decision (Justice Elena Kagan recused herself), the Court struck down most of the Arizona law and limited the permissible range of state activity in the realm of immigration enforcement. To allow each of the 50 states to enact its own immigration-control laws — even if those laws did not conflict with, but instead complemented, federal law — would, in the Court's view, violate the doctrine that "the States are precluded from regulating conduct in a field that Congress, acting within its proper authority, has determined must be regulated by its exclusive governance."

In the eyes of the Court's majority, the regulation of immigration has been so thoroughly dominated by the federal government as to leave virtually no room for action by the states. Justice Antonin Scalia disagreed, writing in his dissent that such a ruling "deprives States of what most would consider the defining characteristic of sovereignty: the power to exclude from the sovereign's territory people who have no right to be there." The majority's opinion, he contended, is supported by "neither the Constitution itself nor even any law passed by Congress."

Nor is it supported by the history of immigration in the United States. As Scalia noted, "In light of the predominance of federal immigration restrictions in modern times, it is easy to lose sight of the States' traditional role in regulating immigration — and to overlook their sovereign prerogative to do so." He is correct: Federalism and immigration have interacted in complicated ways since our republic was created. In fact, until the late 19th century, immigration was an issue largely left up to individual states to regulate.

A look at the history of our immigration system can therefore offer some important clarification of the dispute at the heart of Arizona v. United States. But that history also has a great deal to say about our approach to immigration policy more broadly. After all, Arizona did not resolve the much bigger dilemma facing the nation: how, exactly, we should repair a national immigration system that is quite clearly broken. Designed almost five decades ago, that system has ceased to function effectively, to suit the needs and circumstances of today's society and economy, and to retain the support of the public. It is precisely the failure of that system that has driven Arizona and other states to try to fix the problem themselves, and that has prompted lawmakers at the national level to spend the better part of the past decade in pursuit of "comprehensive immigration reform." That effort has tortured the nation's politics and stoked controversy surrounding questions of race and national identity — and yet has achieved essentially nothing. Why?

Here, too, history points to the answer: Our immigration policies, and the role the federal government plays in them, tend to follow American political trends more broadly. Large reforms of immigration laws have coincided with sweeping changes in the public's expectations of the federal government — during the Progressive era, in the wake of World War I, and in the heart of the Great Society period. We may well be in the midst of such a dramatic shift in our approach to government, though it is not yet evident precisely where these changing expectations will lead. We should not be surprised, then, that our immigration debate has, to date, been similarly inconclusive.

So what should Americans concerned about the very urgent problems posed by our broken immigration system do? After Arizona, in which direction should they expect reform to go, and in which direction should they push those policies? As with other crucial questions about our immigration policy, the answers may well lie in a careful examination of American history.

IMMIGRATION AND FEDERALISM

The United States Constitution says less about immigration than most Americans assume. Article I, Section 8, grants to Congress the power "to establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization." That's all. Congress has the authority to pass laws governing how immigrants can become citizens — a power that would naturally fall to the national government. But on the question of who should determine just who can enter the country and under what conditions, the Constitution is silent.

As a result, during America's first century, regulating entry into the country was a power left up to individual states. Apart from laws dealing with immigrant naturalization, Congress concerned itself with only a few modest regulations of the conditions aboard passenger ships traveling to the United States. The states would decide who could enter their ports, and their laws on that front dealt almost entirely with the exclusion of three types of individuals: criminals, paupers, and people suffering from contagious diseases.

The resulting immigration system would strike us as exceptionally open and liberal. But during the nation's early decades, immigration levels were in fact relatively low: Between 1790 and 1820, only about 100,000 immigrants entered the United States per decade, mostly from the United Kingdom and Western Europe. This pattern began to change in the 1830s, which saw more than 500,000 immigrants arrive (again, almost entirely from Western Europe, especially Germany and Ireland). By the mid-1840s, America was in the midst of a genuine immigration explosion: Nearly 1.5 million immigrants arrived in the 1840s, and almost 3 million arrived in the 1850s (94% of them from Western Europe, according to later estimates by the Immigration and Naturalization Service). Nearly 2 million more arrived in the 1860s, even while the nation was torn by civil war.

The seemingly limitless availability of land as the nation expanded westward meant that these huge waves of immigration did not at first substantially increase the population density of the Eastern states. For a time, the social tensions posed by immigration thus seemed manageable. An exceptionally open immigration policy controlled by the states remained in place, while the federal government managed the naturalization process.

This state of affairs began to change only in 1875, when the Supreme Court, in Henderson v. Mayor of New York, declared that state laws levying taxes on arriving immigrants were an unconstitutional usurpation of congressional power. On its face, the case seemed to revolve around the government's taxing power, not the authority to regulate immigration, but the Court used the occasion to pronounce its disapproval of the lack of uniformity in immigration rules. "The laws which govern the right to land passengers in the United States from other countries ought to be the same in New York, Boston, New Orleans, and San Francisco," the Court declared.

This novel view was very much a reflection of the spirit of the time — an early example of how immigration policy tends to follow the nation's political trends more broadly. A decade after Appomattox, the Court seemed to be in a nationalist mood and unsympathetic to states' rights. The justices thus essentially invented the idea of federal control of immigration policy. But what the ruling lacked in terms of strict adherence to constitutional text and precedent it made up for in terms of pragmatic policy necessity. A rapidly industrializing nation experiencing a huge wave of immigration could no longer leave the question of who was eligible to enter its territory up to individual states; evaluating people entering the ports of New York or Boston was no longer a matter of merely local concern.

For that very reason, Congress was not far behind the Court: The first real federal immigration law was enacted in the same year as the Henderson decision, and restricted the admission of prostitutes, criminals, and some Chinese contract laborers. Congress acted again in 1882, first barring most Chinese immigrants under the Chinese Exclusion Act, and then passing a more general immigration law extending the categories of exclusion to any individual deemed a "convict, lunatic, idiot, or person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge." In 1885, Congress passed the Alien Contract Labor Law, strongly backed by labor groups, which made it illegal for employers to recruit foreigners abroad and pay for their passage to America for the purpose of employing them in the United States.

Yet the federal government lacked an effective mechanism for enforcing these immigration statutes. Enforcement of the new regulations thus rested in an uneasy partnership between Washington and the states, with a large share of the burden falling on New York. At that time, the most commonly used immigration station was Castle Garden in Manhattan's Battery Park; the facility was run by the state of New York in conjunction with Irish and German immigrant-aid societies. The methods that the state and its partner organizations employed in processing immigrants at the station were widely criticized throughout the 1880s, with many complaining that the operations at Castle Garden had become lax and even corrupt.

These charges masked deeper concerns: namely, that America was witnessing both a massive increase in the number of immigrants coming into the country and a change in those immigrants' countries of origin. In the 1870s, some 2.75 million immigrants entered the country; that figure nearly doubled in the 1880s, to 5.25 million. At the same time, America saw more and more immigrants coming from Southern and Eastern Europe — marking the beginning of a demographic shift away from Northern European immigration, a trend that would continue for the next 40 years with enormous social and political consequences.

This influx coincided with the increasing popularity of racialist ideas. Many in the United States believed in a hierarchy of races in which Anglo-Saxons stood as the most superior or most "civilized." Suddenly, more and more immigrants were coming from places farther removed from England and thus allegedly lower on the evolutionary ladder. Well-respected Vermont senator Justin Morrill summarized these views when he said that these new immigrants were "more dangerous to the individuality and deep-seated stamina of the American people....I refer to those...who are as incapable of evolution, whether in this generation or the next." These new immigrants seemed to many to be constitutionally and genetically unfit for democracy and self-government.

In reaction to these concerns, an 1889 congressional report investigating Castle Garden claimed that "large numbers of persons not lawfully entitled to land in the United States are annually received at this port." Such a conclusion was in keeping with the belief that many of these new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe were either criminals, diseased, or somehow incapable of taking care of themselves and therefore barred from entry into the country. A proper system of inspection was supposed to guard against the admission of such types; according to the report, however, one Castle Garden official called the immigrant processing "a perfect farce."

THE ELLIS ISLAND ERA

A new system was needed, and one quickly took shape. With the Immigration Act of 1891, the federal government asserted comprehensive authority over immigration control. And the following year saw the opening of a federal facility in New York Harbor to replace Castle Garden and enforce the new federal law: Ellis Island.

The takeover of immigration by the federal government was mirrored by similar moves in other areas of policy. In a pattern that would be repeated for a century, immigration reform was one facet of a larger rethinking of the role of government in America. It is no surprise that, within a span of four years, Congress not only passed a law taking complete control of immigration and creating a federal Bureau of Immigration (so that it would no longer need to delegate enforcement responsibilities to the states), but also enacted the Interstate Commerce Act (1887) and the Sherman Anti-trust Act (1890), which set the stage for federal regulation of private businesses. All of these laws addressed what was perceived as a wholesale failure of state governments to regulate an increasingly complex and powerful private economy.

The new Bureau of Immigration was the epitome of that great invention of the Progressive era: the federal administrative bureaucracy. Such administrative agencies slowly pushed the boundaries of federal regulatory power, with the immigration service among the trendsetters. Congress even went so far as to limit judicial oversight over the decisions of the federal immigration bureaucracy — at the time, an extraordinary extension of bureaucratic power. If an immigrant felt that officials had unfairly excluded him, the only recourse he had was an appeal up the administrative chain of command in the executive branch, not an appeal to the courts. The Supreme Court's acceptance of this "plenary power doctrine" would shape American immigration law from then on. Congress and the executive branch would have exclusive authority over immigration, and immigrants would have very limited ability to challenge that authority in federal courts.

Under the so-called Ellis Island policy regime that lasted until the mid-1920s, immigrants would arrive (with no prior visa or formal permission) at American ports, where federal officials would inspect them. As long as the immigrants did not fall under one of the explicit categories of exclusion, they could enter the country. The list of such categories included any person "likely to become a public charge," as well as the diseased, criminals, anarchists, polygamists, those with low intelligence, paupers, and prostitutes. In 1917, passing a literacy test (conducted in the immigrant's native language) was added to the entry criteria.

Despite the fairly broad list of categories for exclusion, only 2% of those arriving at Ellis Island were excluded (and about 75% of immigrants to the country were processed through Ellis Island during this period). The chief reason for the low rejection rate was that the steamship companies that brought immigrants over were required by law to take people denied entry back home to Europe, which gave those companies an enormous financial incentive to avoid bringing over passengers who might be rejected by American immigration officials. The companies thus conducted their own screening of potential immigrants in Europe, and refused tickets to many of them. By one reasonable estimate, some 68,000 potential immigrants were refused steamship tickets at European ports in 1906. The same year, some 6% of immigrants at the Port of Naples were denied tickets to America.

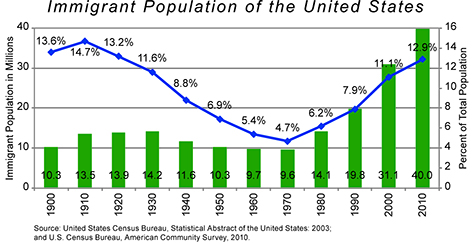

But despite such rejections, these formal and informal rules permitted a massive wave of immigration to America. In the first decade of the 20th century, 8.2 million immigrants arrived in the United States. The year 1907 — when that wave of immigration crested — saw nearly 1.3 million arrivals, a number that was not surpassed until 1990. It is also worth noting that those 1.3 million immigrants came at a time when the nation's population was less than one-third of its current size; today, this would be equivalent to roughly 4 million immigrants arriving in one year. (By comparison, in the period from 2000 to 2005, which almost certainly saw the largest number of immigrants in our history, roughly 1.5 million immigrants entered the country each year, about a third of them illegally.) By 1910, 15% of Americans were foreign-born, and in New York and Chicago, an amazing 80% of the population consisted of either immigrants or the children of immigrants. From 1892 to 1924, the nation welcomed a total of roughly 20 million immigrants.

But the First World War and its aftermath marked the beginning of the end of the Ellis Island era in immigration policy (although the station itself would remain open until 1954). The war had left many with the sense that Europe was a boiling pot of ideological radicalism — whether communism, socialism, or anarchism — and that large numbers of immigrants would bring these toxic ideas to America and threaten the nation's peace and security. The years following the war saw calls for "one-hundred percent Americanism" and denunciations of hyphenated Americans. The Russian Revolution fanned these fears of dangerous foreign extremism even further.

Such concerns led Congress to pass two laws — one in 1921 and the other in 1924 — that restricted the number of immigrants who could arrive in the country in any one year and instituted annual quotas based on immigrants' countries of origin. Once again, a broader trend in American politics — in this case a turn toward isolationism — was reflected in immigration policies.

The quotas were created both to reduce the total number of immigrants and to stop the demographic transformation overtaking America by favoring northern Europeans at the expense of everyone else. These restrictions marked a drastic shift in immigration policy, and they proved extremely popular: The laws establishing this new immigration regime passed by overwhelming margins, and the laws' opponents found themselves on the fringes of the public debate.

The new laws were also highly effective. By the late 1920s, an average of 300,000 immigrants arrived a year, sharply down from the high levels of the previous decades. Moreover, most of these immigrants came from Great Britain and other Northern European countries, rather than from Southern and Eastern Europe, regions deemed to be greater hotbeds of radicalism.

The Great Depression and the Second World War kept immigration levels extremely low, below even the modest legal quota levels. By the mid-1950s, America's immigration numbers were, on average, roughly the same as they had been in the late 1920s — about 250,000 to 350,000 per year. As immigration from the Western Hemisphere was exempt from strict quotas, this period saw a relative increase in immigration from Latin America, intensified by the creation of the Bracero Program, which provided for the entry of temporary guest workers from Mexico. Overall, immigration levels remained relatively low for the two decades following the war.

THE CIVIL-RIGHTS ERA

All of that changed, like so much else, in the mid-1960s. Recent years have seen an intensified liberal nostalgia for the 1950s and early '60s, viewed especially by those on the left as a kind of economic golden age with rising wages, strong unions, high marginal tax rates, and relative job security. Missing from this narrative is the fact that this era was also a period of exceptionally low immigration: By 1960, only 5% of Americans were foreign-born.

It is no coincidence that this low ebb in American immigration came at the same time as the civil-rights movement for African Americans, just as the Ellis Island period of high immigration coincided with the rise of Jim Crow segregation. During the Progressive era, reformers paid little attention to the rights of black Americans, preferring to focus instead on the problems of urban poverty, which were partially a result of high immigration. By the 1950s, however, immigration was no longer much of an issue — and so the country slowly turned its attention to righting the wrongs of legal segregation.

But the civil-rights movement in turn drove a major change in immigration policy. The passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which banned many forms of discrimination by race, made for a stark (and for many an embarrassing) contrast with the blatant racial and ethnic discrimination still codified in America's immigration laws. Even as late as the 1960s, the discriminatory quotas from the 1920s remained in place. These were heavily skewed in favor of Northern European countries and against nearly everyone else in the Eastern Hemisphere. For a person from Greece or South Korea or Somalia, emigrating to the United States was extremely difficult. Vice President Hubert Humphrey summed up the views of many when he said: "We must in 1965 remove all elements in our immigration law which suggest that there are second-class people.... [W]e want to bring our immigration law into line with the spirit of the Civil Rights Act of 1964."

This produced the 1965 Immigration Act, also known as the Hart-Celler Act, which has shaped immigration policy for nearly half a century. It is now largely forgotten that Hart-Celler was an important part of President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society agenda, alongside the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, Medicare, Medicaid, federal aid to schools, anti-poverty programs, and federal support for the arts and humanities. The passage of the 1965 immigration reform, along with these other bills, represented the height of post-war American liberalism. Once again, immigration reform was part of a larger transformation of the federal government's role in the life of the nation.

At the time, Hart-Celler was widely hailed for bringing a measure of fairness to American immigration policy, and it is still widely viewed as a "liberal" law. Yet like much of the Great Society agenda, Hart-Celler stands as a monument to the law of unintended consequences. As historian Roger Daniels has observed, "Much of what it has accomplished was unforeseen by its authors, and had the Congress fully understood its consequences, it almost certainly would not have passed." The law set forth a complex series of policies that, over time, have yielded a system that is so generous as to undermine the nation's faith in our ability to control immigration, yet simultaneously so restrictive as to create the modern problem of vast illegal immigration.

What went wrong? Congress abolished the longstanding exclusions of Asian immigrants as well as the discriminatory quotas based on national origin that dated to the 1920s — moves that were surely long overdue. But the new law did not eliminate quotas completely. Instead, it created overall annual caps of 170,000 visas for immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere (with no country granted more than 20,000 visas per year) and of 120,000 visas for immigrants from the Western Hemisphere.

Most supporters of the law assumed that this was a necessary but modest reform — one that would eliminate racist categories from our immigration laws, but would neither significantly increase the total number of immigrants entering the country nor change the composition of the immigrant pool. If anything, these supporters believed that the bill would benefit immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. "This bill is not designed to increase or accelerate the numbers of newcomers permitted to come to America," Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach said in February 1965. "Indeed, this measure provides for an increase of only a small fraction in permissible immigration." Senator Edward Kennedy, a key supporter of the bill, claimed: "First, our cities will not be flooded with a million immigrants annually. Under the proposed bill, the present level of immigration remains substantially the same....Secondly, the ethnic mix of this country will not be upset."

Ultimately, however, these claims and assumptions proved to be wrong. What seemed at the time to be the most innocuous part of the law turned out to be the most significant: its focus on family unification. American citizens' immediate family members — defined to include spouses, minor children, and parents of naturalized or native-born citizens — were permitted to enter the country outside of the numerical quota system. This meant that, theoretically, they could come in unlimited numbers (though the lumbering bureaucratic process involved in permitting their entry has often limited their migration). Moreover, within the quota system, nearly 70% of new visas would be reserved for more distant relatives of people already in the country. These included the adult children and siblings of citizens, as well as spouses and minor children of immigrants who were permanent residents — so-called Green Card holders — but not yet citizens. Only 20% of visas were set aside for skilled workers.

Under Hart-Celler, the aim of American immigration policy would no longer be economic — aligning the needs of the American economy with people able to meet them — but rather, for the most part, promoting family unification. This seemed like a way to avoid unduly distorting the American labor market and what Kennedy had called "the ethnic mix of the country." But everyone involved failed to see that this approach would eventually lead to large-scale "chain migration": Under the new law, an immigrant could bring over not just his wife and children, but, once he was naturalized, also his parents and siblings, all of whom could then also bring their own family members. The process would then be repeated and would unfold into a new and unintended pattern of American immigration.

To be sure, the new pattern took some time to emerge — and in the early years of the Hart-Celler regime, the law's champions seemed vindicated. In the ten years before the bill's passage, the nation had averaged about 282,000 immigrants per year; in the ten years following, it averaged about 380,000 per year — a relatively modest increase. But beginning in the 1970s, immigration steadily increased, and by the 1980s, America was welcoming more than 600,000 immigrants per year. The changes to America's immigrant pool were not restricted to numbers: The immigrants' nations of origin began to change as well. More of the post-1965 immigrants hailed from Asia and Latin America, while fewer came from Europe. By the 1980s, only 11% of all immigrants to America came from European countries.

At the same time, lawmakers imposed the first quota system for immigrants from the Western Hemisphere. In conjunction with the end of the Mexican guest-worker program, this change made legal migration to the United States more difficult for Latin Americans, especially Mexicans. Yet illegal immigration across the massive U.S.-Mexican border remained relatively easy, and the number of illegal entrants exploded. In 1964, 86,597 illegal immigrants were apprehended and deported. By 1970, that figure had increased to 345,353; by 1975, it had reached 766,600.

Illegal immigration has presented a challenge for authorities ever since the Chinese Exclusion Act and the quotas of the 1920s. But the sheer scope of the problem in the wake of the 1965 law was utterly unprecedented. Thus, over time, the Hart-Celler system left the United States with both an aimless legal immigration regime untethered to the nation's economic needs and a massive tide of illegal immigration that, as yet, policymakers have been unable to control.

A SYSTEM IN CRISIS

By the mid-1980s, there were an estimated 3 million illegal immigrants residing in the United States and at least 200,000 new ones entering each year, according to estimates by the Department of Justice. It was clear that Congress had to intervene. The 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act sought to fix the problem with a mix of amnesty and enforcement. Many people in the country illegally would be allowed to legalize their status, while sanctions were placed on employers who knowingly hired illegal immigrants.

But the law was a failure, and that failure made matters significantly worse. While large numbers of illegal immigrants took advantage of the new amnesty provision, the employer sanctions were never strongly enforced. Amnesty in conjunction with meaningless penalties meant that the problem of illegal immigration only continued to grow: The decade from 2000 to 2010 saw an increase of roughly 5 million illegal immigrants. By 2010, there were an estimated 10 to 13 million illegal immigrants in America.

The policy also had a harmful effect on Americans' attitudes, making immigration an even more difficult political problem. Both the 1965 and 1986 laws ended up breeding cynicism about federal immigration policy. Because of the failures of the 1986 law in particular, there is today a deep distrust of any new amnesty proposal, especially among more conservative voters. The contradictions and unintended consequences of the 1965 law, meanwhile, have weakened support for our entire immigration regime, on both the left and the right. Liberals rightly fault the law for creating much of today's illegal-immigration problem, while conservatives rightly point to the unintended consequences of the law and argue that there was never any popular support for the kinds of changes in immigration that the policy has brought about.

Those changes have involved a huge increase in the overall scope of legal and illegal immigration. Between 1960 and 1969, 3.2 million people immigrated to the United States legally. Between 2000 and 2009, the number was just over 10 million, according to the Department of Homeland Security. Nearly 13% of Americans are now foreign-born — roughly the same percentage as at the height of the early-20th-century immigration explosion. Far from stabilizing the size and origins of the immigrant population in America, the Hart-Celler system has made that population extraordinarily difficult to regulate.

In many ways, of course, the increase in immigration precipitated by Hart-Celler has greatly benefited the nation. It coincided with the long economic boom from 1983 to 2007. America's digital revolution, too, owes much of its success to immigrants, enhanced as it has been by foreign-born entrepreneurs and high-tech workers. Indeed, according to Rohan Poojara of the American Enterprise Institute, more than 30% of scientists and engineers in Silicon Valley are immigrants. Expansions of our refugee policy under the '65 immigration law, meanwhile, have allowed the United States to continue its important (if sometimes inconsistent) role in sheltering victims of the world's most oppressive regimes.

But there can be no doubt that this wave of immigration has also brought problems. Liberals who complain about income inequality and stagnant wages seem to ignore the fact that these trends have coincided with increases in immigration, especially of low-income, low-skilled immigrants. Then there is the larger demographic change overtaking America, as the Hispanic and Asian populations have grown thanks in large part to post-1965 immigration. In 2010, racial minorities accounted for more than half of the population in 22 of the 100 largest metropolitan areas, compared to 14 such areas in 2000 and five in 1990. In 2010, for the first time, the New York City and Washington, D.C., metro areas joined the majority-minority ranks. Demographers predict that by 2050 whites will make up less than 50% of the overall U.S. population.

Although the mainstream culture celebrates diversity and multiculturalism, one need not be a cultural isolationist to see that such vast demographic changes cannot occur without producing real tensions. Above all, they force to the surface complex questions about the nature of American identity and the purpose of American immigration policy. And inquiry into this latter point makes it especially difficult to justify our current immigration regime, which aligns with neither America's national interest nor the public's desires. The system has lost all semblance of purpose.

BEYOND THE IMMIGRATION STALEMATE

It is clearly time for a major overhaul of America's immigration laws, but our political system has been unable to make any progress toward meaningful reform. What are the reasons for this failure to act? And how might understanding the history of American immigration policy help us break the stalemate?

First, we have not made progress toward a new immigration regime because the interests of both major political parties are currently aligned against it. Republicans are caught in something of an immigration bind: They know they must appeal to Hispanics and new immigrant groups if they are to remain a political force, but much of the party's base is angered by illegal immigration, and the party sometimes derives real political benefit from promising to crack down on law-breakers. Hispanic voters care about more than immigration, of course, and Republicans won nearly 40% of the Hispanic vote in the 2010 congressional elections. But it is clear that the rhetoric of immigration restriction does turn off these voters, while the rhetoric of immigration liberalization turns off many conservatives. Democrats, meanwhile, are able to use immigration as a wedge issue with Hispanics and have no political incentive to enact any immigration reform apart from amnesty. Even without amnesty, many Democrats believe they can wait out the clock while demographic changes slowly transform some key states from "red" to at least "purple." Thus neither party is truly motivated to push for reform.

But a second, and deeper, reason for the lack of progress has to do with the way we now understand the immigration question. Because of the origins of the 1965 immigration reform, and because of the changing nature of our common understanding of American identity, we Americans have come to view immigration through the prism of civil rights, rather than through the traditional prisms of assimilation and preserving a common culture. To many academics, politicians, and immigrant advocates today, however, the old Ellis Island model of cultural assimilation seems oppressive and backward, and the immigrant experience is understood through the filters of race and oppression.

Most Americans don't think this way, yet they are still often uncomfortable with the language of assimilation. And so it is in the language of civil rights — despite its obvious unsuitability to the immigration debate (since civil rights, as opposed to human rights, are by definition the rights of citizens of a particular community) — that our immigration conversation has been conducted.

At a practical level, framing immigration as a civil-rights issue means that political compromise is almost impossible. How does one compromise over civil rights? Could civil-rights leaders of the 1950s and '60s have compromised over segregation or voting rights? And understood in these terms, determined enforcement of current laws — as well as most efforts to restrict illegal immigration — are viewed with suspicion. The political and economic questions that have always informed immigration policy now compete with a confused but highly moralistic view that places increased emphasis on the rights of immigrants.

The prospects for serious reform thus look bleak — and not only because of these immigration-specific political and intellectual trends. As we have seen, past immigration reforms have generally occurred along with larger transformations of the role of the federal government — in the early Progressive era, in the isolationist turn following the First World War, and in the Great Society period. Today, as the general political order of the post-war era appears to be breaking down, the nation seems to be approaching another revolution in how we think about government. But the character of that revolution is still far from clear. In many ways, the 2012 election seems likely to be pivotal: We might choose to pursue the European path of social democracy more thoroughly than America ever has, or we might pursue a different path toward a more restrained federal role.

The history of the American immigration debate suggests that the choice we make regarding that larger set of questions — a choice about the nation's character and destiny — will also determine what we do about our crumbling immigration regime. In either case, however, efforts at a comprehensive solution are likely to be futile until the nation has resolved some crucial disputes and made some key decisions about its path in the coming decades.

THE NEXT IMMIGRATION POLICY

In one respect, today's immigration stalemate — and, with it, the state-level effort to more strictly enforce existing federal laws — actually represents something of the spirit of our time. Arizona's aggressive immigration laws reflect a widely felt sentiment: deep frustration with an inept-seeming federal government.

If the early 20th century was a nationalizing period with more and more power flowing to Washington, the more recent trend — at least since the mid-1970s — has been toward federalism, with a push (in rhetoric, at least, if not always in fact) toward returning some power to the states and checking the growth of the federal bureaucracy. It should therefore come as little surprise that some states — having concluded that the federal government has simply not done its job and may be incapable of doing it — would feel emboldened to try to claw back some power over immigration.

Indeed, in its opinion in Arizona v. United States, the Supreme Court seemed somewhat sympathetic. "The National Government has significant power to regulate immigration," the Court held. "With power comes responsibility, and the sound exercise of national power over immigration depends on the Nation's meeting its responsibility to base its laws on a political will informed by searching, thoughtful, rational civic discourse." Had these obligations been met at the national level, there would have been little need for states to intervene.

Legitimate though these state concerns may be, however, their solution is not to be found in 50 separate immigration policies. "Arizona may have understandable frustrations with the problems caused by illegal immigration while that process [of discourse] continues," the Court declared, "but the State may not pursue policies that undermine federal law." And though the power to control immigration may not be explicitly granted to the federal government under the Constitution, it is hard to imagine a modern nation-state in the 21st century in which that power does not rest firmly in the central government's hands.

Nevertheless, this still means, as the Court noted, that the federal government has a responsibility to act on immigration — to pursue reform that reflects a shared "political will," and to forge that agreement through "searching, thoughtful, rational civic discourse." The history of American immigration suggests that this agreement will be reached only when the national mood and the country's politics more broadly are ready for it — and the signs indicate that now is not that moment.

But settling on a sensible immigration policy will be crucial in the coming decades. Without one, it will be impossible to maintain a high standard of living and a dynamic, entrepreneurial economy while also managing the large demographic changes that continue to remake our society. In this sense, the unproductive nature of our immigration debate may be telling us something about the state of the nation more generally. Our decaying institutions have forced us to make enormously consequential decisions about the role of our government, its relationship to the individual, and the direction of the nation. As with immigration policy, our ability to settle these broader disputes satisfactorily is an open question.