Locke, Virtue, and a Liberal Education

Following the Boston Massacre in March 1770, the Massachusetts lawyer and patriot Josiah Quincy, Jr., joined John Adams in defending the British soldiers involved. The sentries had fired into an unruly crowd of civilians, killing three and wounding eight. If convicted, they would hang. In his argument for the defense, Quincy cited three main sources: the Bible, English common law, and the English philosopher whose theories on government would fuel the American Revolution.

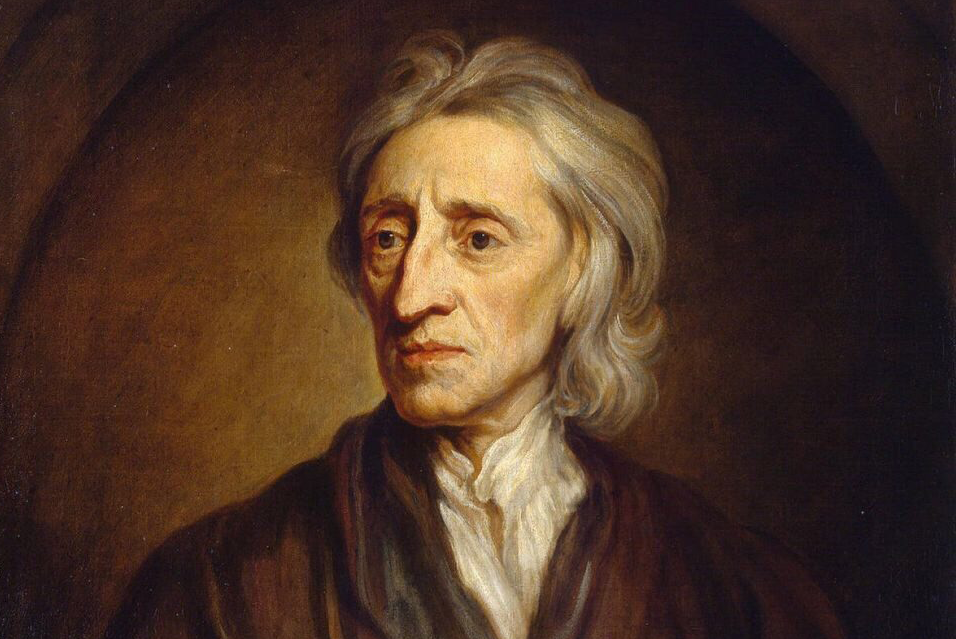

The writings of this philosopher, Quincy argued, represented "the wisdom and policy of ages," coming from a man "who [had] done as much for learning, liberty, and mankind, as any of the Sons of Adam; I mean the sagacious Mr. Locke." After quoting from John Locke's Second Treatise of Government, Quincy concluded his tribute thus: "We cite this author to show the world, that the greatest friends to their country, to universal liberty, and the immutable rights of all men, have held tenets, and advanced maxims favourable to the prisoners at the bar."

The jury found the British soldiers not guilty. At a key moment in America's struggle for independence, against an enraged mob of public opinion, the principle of impartial justice was reaffirmed.

For Quincy, and for other colonial Americans, Locke was more than a political philosopher: He was a man renowned for his "humanity," writes Claire Rydell Arcenas in America's Philosopher: John Locke in American Intellectual Life. He was "a companion in thought and an exemplar." And unlike any other 17th-century author, Locke was for many Americans "an immediate, daily authority" over the conduct of their public and civic lives.

For a growing cohort of conservatives in our own time, however, Locke's influence on the American founding explains the wretched condition of our national culture. The decline of religion, the breakdown of the family, the idolization of the free market, the soul-destroying materialism, expressive individualism, and widespread moral rot: All of these ills are laid at Locke's doorstep, tied to his conceptions of equality, freedom, and natural rights.

According to critics like philosopher Yoram Hazony, Notre Dame's Patrick Deneen, and First Things editor R. R. Reno, the chief aim of Lockean liberalism is to liberate individuals "from the constraints imposed by the natural world." The last half-century of scholarship on Locke has convincingly refuted this portrait. Yet there is a much deeper problem than intellectual laziness among Locke's conservative critics: Not unlike the progressive left, they fail to grasp how the preservation of republican government depends on the inculcation of republican virtues.

LOCKE'S INFLUENCE

In reality, Locke regarded the cultivation of republican virtue as the central task of the educator. Character formation — rooted in the classical Christian tradition — is the subject of Some Thoughts Concerning Education, the collection of letters Locke wrote to his close friend Edward Clarke. According to the late Cambridge historian Peter Laslett, Locke's practical and innovative approach ranks as "one of the most influential" in the history of education. It is largely forgotten today that Locke not only made the definitive case for government by consent; he also promoted, with genuine insight into human nature, an educational philosophy that would produce the kinds of citizens fit for self-government.

Locke composed his correspondence with Clarke during his political exile in the 1680s, when the question of representative government was the subject of intense international debate. Political absolutism was on the rise in Great Britain (under Charles II and James II) and France (under Louis XIV). Meanwhile, religious despotism, practiced by the Protestants in the Church of England and the Catholics in France, threatened Europe's social fabric. Implicated in a failed plot to assassinate the English monarch, Locke fled to the Netherlands, where he reflected on several major themes: the nature of human understanding, the necessity of religious freedom, and the role of education in creating a more liberal society. Locke's educational advice reflects the turmoil of his age:

By what fate vice has so thriven amongst us these few years past, and by what hands it has been nursed up into so uncontrolled a dominion, I shall leave to others to inquire. I wish that those who complain of the great decay of Christian piety and virtue everywhere, and of learning and acquired improvements in the gentry of this generation, would consider how to retrieve them in the next. This I am sure, that, if the foundation of it be not laid in the education and principling of the youth, all other endeavours will be in vain.

This is precisely what Locke set out to explain in his letters: how to transmit traditional piety and moral character to the next generation. "[N]othing that may form children's minds is to be overlooked and neglected," he declared, and "whatsoever introduces habits, and settles customs in them, deserves the care and attention of their governors."

Locke touched a nerve. Probably no thinker had a greater impact on the educational philosophy of the Anglo-American world in the century after his death. In Sermons on the Religious Education of Children, for example, Congregationalist minister Philip Doddridge cited Locke alongside King Solomon. Historian Samuel Pickering, Jr., observed that Locke's writings on education "were practically biblical" in their importance to the emerging middle class. "By the 1730s," he pointed out, "Locke's educational ideas had been absorbed into the thought of the century."

What ideas animate Locke's educational handbook? More than any of his other works, Some Thoughts Concerning Education demolishes the crude caricature of Locke as a secular hedonist made vogue by political philosopher Leo Strauss in the 1950s and parroted more recently by numerous voices on the new right.

Instead of Locke the economic materialist, we find a man admonishing parents to curb their child's desire for material goods at every turn. Instead of Locke the Enlightenment utopian, we meet a student of the Bible with a sober view of the doctrine of the Fall. Instead of Locke the radical individualist, we see a patriot trying to nourish a culture of responsible citizenship. And instead of Locke the moral agnostic, we encounter a religious believer who defined true virtue as "the knowledge of a man's duty, and the satisfaction it is to obey his Maker, in following the dictates of that light God has given him, with the hopes of acceptation and reward." In short, we find in Locke's philosophy of education a deep and abiding concern for virtue.

EDUCATING FUTURE LEADERS

It may seem odd that a middle-aged bachelor would offer child-rearing advice. Locke himself confessed, "I am too sensible of my want of experience in this affair." But Edward Clarke, married with two young children, sought him out. Locke had served as a tutor to young students at Oxford; was given charge over the grandson of his political mentor, Lord Shaftesbury; and had gained a reputation for engaging the minds of children on serious topics. "It is quite clear," writes biographer Roger Woolhouse, "that he was a keen and reflective observer of the young."

There is a sense of urgency in Locke's correspondence, a conviction that what a child learns during his earliest years creates "habits woven into the very principles of his nature." The willful neglect of this truism probably accounts for most of the social problems ravaging America and the West today.

Locke's advice was intended for the sons of English gentlemen, who were expected to set an example of civility and integrity in their public and private lives, so the stakes were high. Elsewhere in his writings, he explained that a gentleman should devote special attention to "moral and political knowledge" on those studies "which treat of virtue and vices, of civil society and the arts of government, and will take in also law and history." English gentlemen were expected to engage in public affairs, and Locke hoped to influence the quality of their leadership.

Nevertheless, Locke did not aim his counsel exclusively at one particular class; the moral code he recommended befitted "a gentleman or a lover of truth." Neither did Locke believe that gender made a significant difference in education. Writing to Mrs. Clarke in January 1684, he said that nothing in his previous letter about the education of her son required alteration with respect to her daughter; he saw "no difference of sex in your mind relating...to truth, virtue and obedience." The exchange affords a glimpse of what I call Locke's "democratic conscience" — his belief in the universal human capacity to apprehend moral and spiritual truths. This conviction anchored the views of human equality and independence that he expressed in his political writings.

CURBING THE APPETITES

Locke's modern critics allege that he viewed man in purely economic terms — that behind his enthusiasm for private property lurked a craven materialism, a blank check for instant gratification. The decidedly anti-materialist message of Some Thoughts plainly undermines that claim.

An overriding theme of Locke's letters is that children must learn to restrain their desires — not just for frivolous or sensual things, but even for innocent pleasures. If a child asks to be given certain clothes or other "trifles" that he doesn't need, for example, the mere asking should ensure that he does not get them. "The best for children is, that they should not place any pleasure in such things at all, nor regulate their delight by their fancies, but be indifferent to all that nature has made so." Locke acknowledged that "tender parents" may find this approach too severe. Nevertheless, he insisted it is necessary if children are to grow into respectable adulthood:

By this means they will be brought to learn the art of stifling their desires, as soon as they rise up in them, when they are easiest to be subdued. For giving vent, gives life and strength to our appetites; and he that has the confidence to turn his wishes into demands, will be but a little way from thinking he ought to obtain them....The constant loss of what they craved or carved to themselves should teach them modesty, submission, and a power to forbear.

The same Spartan attitude, he believed, should be applied to children's physical training. Parents should not shield their children from all physical discomforts, because hunger, thirst, lack of sleep, and weariness from work "are what all men feel." These inconveniences can serve a good purpose: They are signposts on the road to character. "The pains that come from the necessities of nature," he argued, "are monitors to us to beware of greater mischiefs....But yet, the more children can be inured to hardships of this kind, by a wise care to make them stronger in body and mind, the better it will be for them."

So much for Locke as the Epicurean playboy.

THE LOVE OF LEARNING

Although parents and tutors must take pains to curb the desire to have, they should never quash the desire to know. "Curiosity," Locke advised, "should be as carefully cherished in children, as other appetites [are] suppressed." He rejected "the ordinary method of education," which involved "the charging of children's memories, upon all occasions, with rules and precepts," all quickly forgotten. In The Educational Writings of John Locke, John William Adamson explains that in Locke's view, attempts to compel students to learn would fail. Another form of motivation was necessary.

Locke wanted children's education to be engaging and enjoyable, both intellectually and emotionally. "None of the things they are to learn should ever be made a burden to them or imposed on them as a task," he contended. "Whatever is so proposed presently becomes irksome." Locke also rejected the "rough discipline of the rod," instead recommending that parents direct their child's interests, likes, energy, and creativity graciously.

How might parents and educators captivate children in this way? Locke saw a strong connection between the love of learning and the love of freedom that engages children in their play. In this he echoed Montaigne, who observed that "children's games are not games; we ought to regard them as their most serious occupations." Locke encouraged any recreation that does not endanger the child's health, deeming such play "as necessary as labor or food." Recreation, he believed, will help create deep bonds between children and their educators, who will be free to talk with their charges "about what most delights them." The impact on children will be transformative:

[T]hey may perceive that they are beloved and cherished and that those under whose tuition they are, are not enemies to their satisfaction. Such a management will make them in love with the hand that directs them, and the virtue they are directed to.

To achieve all this, Locke acknowledged, requires "patience and skill, gentleness and attention." This is one reason Locke rejected state education and urged parents to teach their children at home, with the help of carefully chosen tutors. The moral formation of their children during this crucial season of their lives was the most important task of both mothers and fathers; it could not be left to chance. With this in mind, Locke urged fathers to make their sons their friends "as fast as their age, discretion, and good behaviour could allow it."

So much for Locke as the enemy of the traditional family.

PROPERTY AND THE WILL TO POWER

Many interpreters of Locke have assumed (wrongly) that his conception of the "state of nature" was lifted from Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan. For Hobbes, the state of nature acknowledges no fundamental moral law, leaving human beings at each other's throats, desperate for an all-powerful Sovereign to preserve their individual lives. But in Locke's state of nature, there exists a known and enforceable moral law, which obliges everyone not only to preserve his own life, but also the life of his neighbor:

Children should from the beginning be bred up in an abhorrence of killing or tormenting any living creature, and be taught not to spoil or destroy any thing....And truly, if the preservation of all mankind, as much as in him lies, were every one's persuasion, as indeed it is every one's duty, and the true principle to regulate our religion, politics, and morality by, the world would be much quieter, and better natured than it is.

Unlike Hobbes, Locke sought to "instill sentiments of humanity" at the earliest possible age. This is essential, he wrote, because human nature inclines us in the opposite direction: "I told you before that children love liberty....I now tell you they love something more; and that is dominion: and this is the first original of most vicious habits, that are ordinary and natural." Locke's anthropology here deserves attention: For him, the lust to dominate is "ordinary and natural" for all human beings. Scholars debate Locke's religious beliefs about the effects of the Fall, but the glib association of Locke's views with those of the Enlightenment philosophes — who assumed mankind's essential goodness — cannot be credibly maintained.

Locke argued that the "love of power and dominion shows itself very early" among the young, "almost as they are born." This impulse appears in a child's desire to possess things — whatever he wants and whenever he wants it. "[T]hey would have property and possession, pleasing themselves with the power which that seems to give, and the right they thereby have to dispose of them as they please." Locke identified this disposition as the source of "almost all the injustice and contention that so disturb human life." It is to be rooted out, he wrote, at almost any cost.

Is this the same Locke famous for his defense of private property? To be sure, the concept of private property is indispensable to Locke's triad of natural rights: As the fruit of human labor, the possession of property is an inalienable right and deserves the same vigorous protections as life and liberty. Indeed, in 17th-century Europe, with its political and religious authoritarianism, the seizure of property was the favored technique to produce compliant citizens. It needed special protection.

Nevertheless, the acquisition of property, absent a strong moral culture, endangers a child's soul. "As to the having and possessing of things," Locke observed, "teach them to part with what they have, easily and freely to their friends." Parents and tutors must determinedly combat avarice in children and replace it with generosity:

Covetousness, and the desire of having in our possession and under our dominion more than we have need of, being the root of all evil, should be early and carefully weeded out, and the contrary quality of a readiness to impart to others, implanted....Make this a contest among children, who shall out-do one another this way; and by this means, by a constant practice, children having made it easy to themselves to part with what they have, good nature may be settled in them into a habit, and they may take pleasure, and pique themselves in being kind, liberal, and civil, to others.

Locke's treatment of private property, like so much else in his political writings, has been seized upon by partisans and stripped from its larger context. Libertarians embrace him for writing that "the preservation of property" is "the chief end" of political society. The new right (along with the progressive left and socialists) excoriate Locke for his supposed idolization of property. But when Locke called the protection of "property" the chief aim of government, he was referring collectively to his triad of natural rights. For Locke, rights to life, liberty, and property belong to individuals, who in turn belong to their Creator. As Locke explained in the Second Treatise, every person is "the workmanship of one omnipotent and infinitely wise Maker...sent into the world by His order and about His business; they are His property." As such, man's natural rights cannot be taken away without violating God's moral law.

Intelligent critiques have been made of the destructive effects of modern capitalism on personal and social relations. But talk of Locke as the architect of the clawing consumerism of our age offers no useful contribution to that debate.

GOD, MORALITY, AND THE REPUBLIC

The author of Some Thoughts made the theme of our social obligations to one another — ethical and spiritual — the subtext for the entire work. When Locke urged parents to teach their children fortitude — "the guard and support of the other virtues" — it was to enable them to perform their duties to family and nation. This is the reason, Locke explained, why he delayed discussion of academic subjects until the end of his correspondence: It is the "least part" of a child's education.

This might appear as a paradox coming from a man of letters, a bibliophile with some 4,000 titles in his collection. Indeed, Locke's intellectual curiosity seemed boundless. Among his possessions were works of philosophy, history, politics, science, medicine, law, theology, geography, and travel. His books were written in numerous languages and spanned the course of Western civilization. His library exceeded that of Isaac Newton in both size and range. Nevertheless, he believed that mastering subjects was of marginal utility if other things were lacking. "Reading, and writing, and learning, I allow to be necessary," Locke noted, "but yet not the chief business."

The chief business, in Locke's estimation, is to develop men and women of strong character, cultivating the traits necessary for responsible citizenship in the commonwealth. "For I think it every man's indispensable duty, to do all the service he can to his country; and I see not what difference he puts between himself and his cattle, who lives without that thought." Contrary to the claims of the national conservatives, Locke was no enemy of patriotism.

Perhaps most importantly, for Locke, as for the American founders, producing such citizens depended on religious belief:

As the foundation of this, there ought very early to be imprinted on his mind a true notion of God, as of the independent supreme Being, Author, and Maker, of all things, from whom we receive all our good, who loves us, and gives us all things; and, consequent to this, instil into him a love and reverence of this supreme Being.

Living in an era of sectarian violence, Locke cautioned against probing too deeply into the mysteries of faith. Too many people, he observed, fail to grasp their own limitations in this regard and "run themselves into superstition or atheism." This call to intellectual modesty appears elsewhere in Locke's writings. In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which Locke completed during his letter-writing period to Clarke, he argued that "the busy mind of man [ought] to be more cautious in meddling with things exceeding its comprehension." The wise seeker of truth, he wrote, knows when "to sit down in a quiet ignorance of those things which, upon examination, are found to be beyond the reach of our capacities."

The best way to encourage piety in youth, according to Locke, is to set an example for them to follow:

And I am apt to think the keeping children constantly morning and evening to acts of devotion to God, as to their Maker, Preserver, and Benefactor, in some plain and short form of prayer, suitable to their age and capacity, will be of much more use to them in religion, knowledge, and virtue, than to distract their thoughts with curious inquiries into his inscrutable essence and being.

Locke cared deeply for the spiritual condition of young people, believing, as he wrote in A Letter Concerning Toleration, that man's "highest obligation" is to seek God's favor, since "there is nothing in this world that is of any consideration in comparison with eternity." This is a major theme in all of Locke's writings defending religious liberty: the right — indeed, the obligation — to freely seek and embrace the path to salvation and find peace with God. Genuine faith, Locke insisted, must be the result of individual choice, "the inner persuasion of the mind," uncoerced by church or state. "No way whatsoever that I shall walk in against the dictates of my conscience," he asserted, "will ever bring me to the mansions of the blessed."

One of Locke's stated objectives in Some Thoughts is to educate children in such a way that they will embrace the truths of Christianity. Toward this end, he cautioned against feeding children too much of the Bible before their minds are ready. Such "promiscuous reading" of the Scriptures, he wrote, would create "an odd jumble of thoughts" that would only confuse them. Instead, he suggested they be introduced to the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, many of the stories of the Bible, and the teachings of Jesus, which should be "so often read, till they are thoroughly fixed in his memory." The aim, Locke explained, is for the teachings of the Bible to "be inculcated as the standing and sacred rules of his life and actions."

So much for Locke as the godless Hobbesian.

TEACH YOUR CHILDREN WELL

An honest commitment to moral and spiritual truth, wherever it could be found, was perhaps the most distinguishing mark of Locke's own intellectual journey. He prized truth-seeking and truth-telling as among the highest of virtues: Parents could give no better gifts to their children than these.

"We are not to entrench upon truth in any conversation," Locke admonished, "but least of all with children; since, if we play false with them, we not only deceive their expectation, and hinder their knowledge, but corrupt their innocence, and teach them the worst of vices." Society, he argued, bears a special obligation to children by virtue of their vulnerability and the consequences of failing them. "They are travellers newly arrived in a strange country, of which they know nothing: we should therefore make conscience not to mislead them."

It is hard to imagine a more damning indictment of our own age. Our children must function in a society awash in lies, falsehoods, distortions, and omissions — all trumpeted by educators, the media, the entertainment industry, the political class, and even the medical and scientific communities. Propaganda, not truth, is the coin of the realm.

This decay of our moral culture comes as a repudiation, not a fulfillment, of Locke's philosophy — and especially his educational theory. In light of Locke's clearly articulated thoughts concerning education, it seems obvious that ideology — rather than an informed view of the origins of liberal democracy — lurks behind much of the contemptuous treatment of Locke and the liberal tradition he helped establish.

Which Lockean ideals, we must ask, have so corroded family, community, church, and nation? R. R. Reno offers a strident verdict: "Locke's ideal society is...a free association of individuals, unbound by duties that transcend their choices." In Regime Change, Patrick Deneen portrays Locke as an apostle of soulless free-market materialism. Locke's ultimate hope, he writes, was that the yearning for material comforts "would eclipse spiritual, cultural, or transcendent aspirations." With Locke's help, duties to family would be seen "as a burden upon personal autonomy" and constraints on personal liberties "were to be largely eviscerated." Yoram Hazony, author of The Virtue of Nationalism, singles out Locke for delivering a "closed system" of secular-rationalist principles antithetical to traditional beliefs and institutions. "[T]here is nothing in the liberal system that requires you, or even encourages you, to also adopt a commitment to God, the Bible, family, or nation," he writes. Instead, the application of Lockean principles — in every instance — has guaranteed "the dissolution of these fundamental traditional institutions." Like other members of the new right, Hazony condemns Lockean liberalism as fundamentally at odds with "the Anglo-American conservative tradition."

It is reasonable to wonder, with all due respect, whether these critics have read any of Locke's works. This brand of "conservatism," disconnected from historical realities, is a creature of recent invention. On March 7, 1766, for example, when Lord Chancellor Charles Pratt addressed the House of Lords to oppose Britain's attempt to tax the American colonists without their consent, he turned to Locke for support: "His principles are drawn from the heart of our constitution, which he thoroughly understood, and will last as long as that shall last."

It is time to admit an obvious possibility: that the leaders of the American Revolution, along with their principled defenders in Great Britain, understood better than disillusioned 21st-century academics what Locke's writings meant for the cause of human freedom.

Talk of Locke as the serpent in the garden — the thinker who unleashed the sins of materialism, expressive individualism, and militant secularism into the world — is bound up with mistaken schemes to reverse the decay. The advocates of national conservatism, Catholic integralism, and common-good constitutionalism have at least two things in common: They misrepresent and therefore reject the core tenets of Lockean liberalism, and, consequently, they are enamored with state power as the guarantor of a virtuous society.

Their short memories need refreshing. Locke's earliest writings on politics and religion — from around the time of the Restoration in 1660 — reveal him as a staunch defender of the monarchy and the national church. But as the Restoration project quickly degenerated into autocracy and religious repression, Locke reversed himself, emerging as the most powerful voice in the 17th century for the principles that would form the bedrock of America's experiment in ordered liberty: natural equality, individual rights, religious freedom, the separation of church and state, government by consent, and the right to resist tyrannical government.

It seems likely that Locke elevated the role of education because he watched with horror as political and religious authoritarians — hell-bent on implementing their vision of "the good society" — ran roughshod over the rights and freedoms of ordinary citizens. Locke offered a better path to a more just, humane, and unified society, not only by the application of his political principles, but through the careful moral and religious formation of the next generation. "The well educating of their children is so much the duty and concern of parents, and the welfare and prosperity of the nation so much depends on it," he contended, "that I would have everyone lay it seriously to heart."

Our collective failure to give children an education in virtue lies at the root of the nation's moral crisis. John Locke and the architects of the liberal political tradition did not create the pathologies that afflict us — rather, they provided a remedy. We would do well to make use of it.