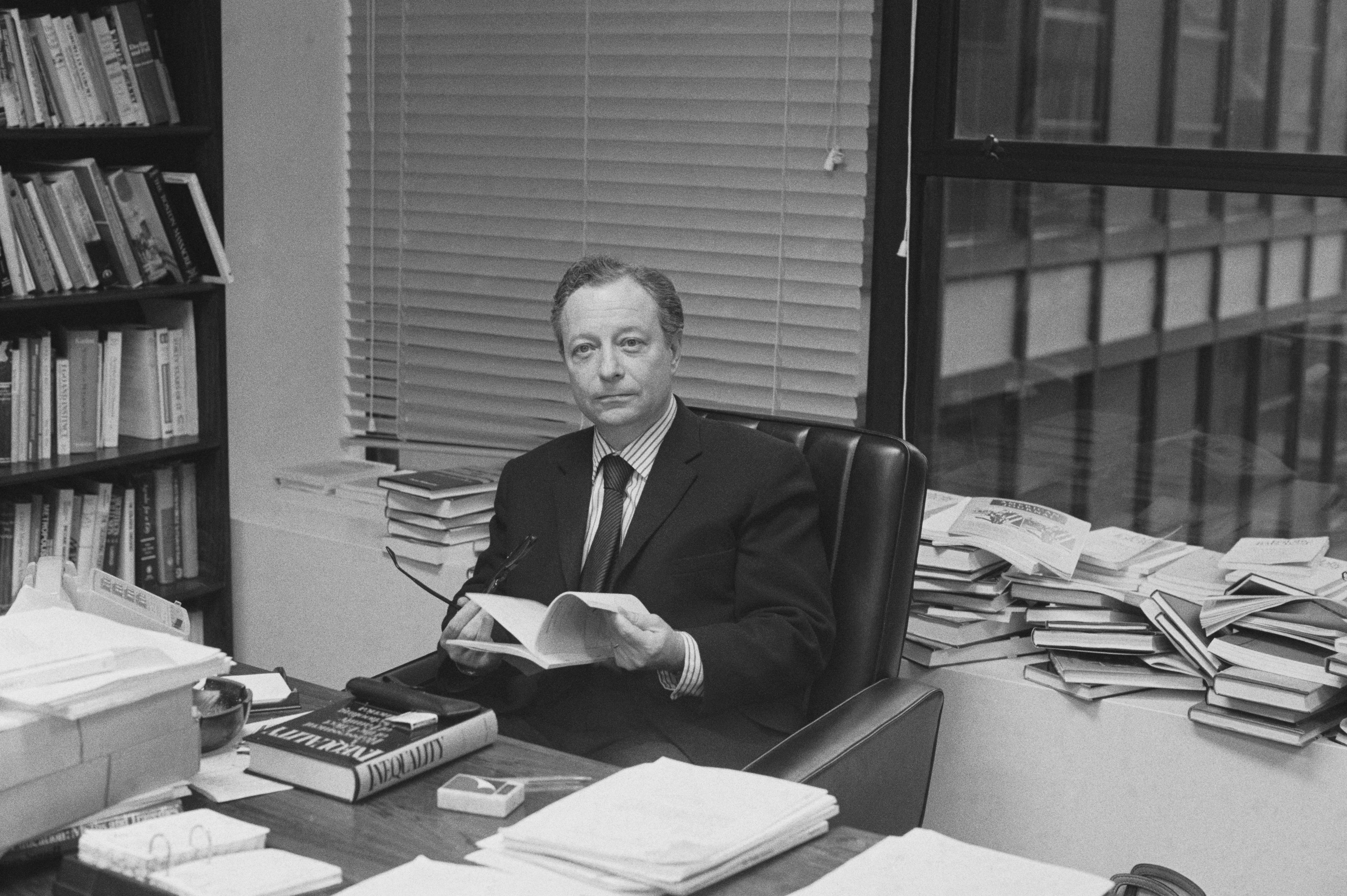

Irving Kristol, Jewish Realist

What does it mean to think for oneself? Isaac Newton is famously pictured under a tree, the notion of gravity having occurred to him by the fall of an apple "as he sat in contemplative mood." So he told his biographer, but elsewhere he paid tribute to the scientists and philosophers who had honed his contemplative mind, saying, "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants." An independent mind is cultivated by a tradition of intellectual independence and enabled by a society that allows such minds their freedom.

Irving Kristol had such an independent mind. Like Newton, Kristol's bold intellect was also formed by respect for a long tradition of critical thinkers. In his case, this was a rabbinic tradition whose mode of thought he had imbibed from the culture of his youth, even though he never quite embraced it. It is a mode of thinking that grapples with the reality of human nature, and it is fundamental to understanding Kristol and his legacy. It set him apart from his fellow intellectuals who disdained religion, and gave him the wisdom to see more clearly the foibles of his fellow man and the dangers they posed to a healthy society and self-governance.

His unique style of thinking allowed Kristol to account for the permanence of man's nature. And as a look at Kristol's intellectual development will show, many of our most painful national divisions today fall along the same fault lines Kristol saw in the 1970s: From racism to inequality, from over-confident bureaucrats to socialist utopianism, we are fighting the same battles over again. Kristol's always-spirited responses to these persistent ideas of the left, and their basis in his profound understanding of man's foibles, have much to teach us about how to approach our own political moment. His distinctive approach to thinking about problems — his role as a kind of rabbinic intellectual — provides an example we would be wise to follow.

EVOLVING ATTACHMENTS

Irving Kristol was born in New York in 1920, and lived a life so much in keeping with his ideas that he blended the two in his memoir, Neoconservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea. He was a man in harmony with himself — not in love with himself, which can lead to intellectual hubris, but at home with himself in the same way he was comfortable with his formative upbringing.

His Yiddish-speaking immigrant parents seem to have taken their Jewishness so much for granted they could afford to ignore some of its rituals, and this approach evolved into his own easy-going non-practicing orthodoxy. Nonetheless, his mother kept a kosher kitchen, and his parents made sure that, in addition to public school, he attended Hebrew school three times a week, where he learned to read the Bible and prayers in Hebrew. (He was thus able to recite the memorial Kaddish prayer for his mother, who died when he was just 16.) When his interest in Judaism and religion deepened in later years, he built on this foundation, and while he never became a Jewish scholar, he thought profoundly and wrote knowledgeably about Jewish life and ideas.

Kristol followed what was then the standard educational path of clever New York boys from poor families. He attended City College, where he was drawn into one of the famous cafeteria "alcoves" of argument. He belonged to the Trotskyist group of Alcove No. One, whose fiercest competitors were the Stalinists of Alcove No. Two. He describes his original drift into Marxism as mostly following the lead of his friends, who included fellow alcove members Daniel Bell, Nathan Glazer, Irving Howe, and Seymour Martin Lipset.

The leftward shift among young Jews at the time was not limited to Kristol's alcove set, of course. A variety of intellectuals and critics associated with the quarterly magazine Partisan Review, which was launched by the American Communist Party, also reflected this trend: Lionel Trilling, Diana Trilling, Harold Rosenberg, Meyer Schapiro, Lionel Abel, and Partisan Review editors William Phillips and Philip Rahy all contributed to a particular type of Jewish leftism. (A number of them attended City College as well.) But Kristol remained enamored of communism only through his early 20s, and spent the rest of his life revising this earlier enthusiasm.

One of the things that changed Kristol was serving as an infantryman in Europe. When he returned to civilian life after the war, he began his lifelong career as a writer, critic, and editor — first at Commentary magazine, then in England as co-editor of Encounter, and finally as founding editor and publisher of two leading American journals, The Public Interest and The National Interest. He situated himself as a resurrected Publius, renewing the spirit of the Federalist Papers for his generation to keep the American people united and stalwart in the face of new challenges.

Although Kristol did not dwell much on how his army service in Europe affected his thinking, a short piece of experimental fiction that he published in Commentary after the war provides a glimpse into that unsettling time. "Adam and I" is written in the first person and describes an encounter between the narrator, a uniformed Jewish American soldier, and Adam, a self-described survivor of Auschwitz. The two meet in the spring of 1945 at Zionist headquarters in Marseille, when Adam approaches the American to ask him for a smoke. The narrator admits, "He didn't at all fit the picture that I had imagined — or that had been imagined for me — of the liberated Jew." They walk together to a nearby café, and an uncomfortable acquaintance begins.

Adam is a slippery character. He is in no hurry to get to Palestine, he explains. Having recently learned that his father is alive, he feels compelled to return to Poland to reunite with the only other surviving member of his family. To do so, he needs things from the American — specifically a gun. The narrator slowly realizes he is no more than a soft touch for this kid who has learned to live on the sly.

Henry James had already explored the theme of innocent Americans coming to grips with European cunning, making this an epigone's version of a similar plot. Adam strips the narrator of false pride, false humility, and false illusions about both the newly liberated Jew and himself, the would-be liberator. The war is denied any redemptive lessons. Yet Kristol's narrator also sets aside his scruples and doubts in order to act, in this case by supplying a fellow Jew with a weapon: a small step for man, a giant leap for the intellectual who normally luxuriates in indecision.

This venture into fiction was unique for Kristol, but his assumption of responsibility was not. He encountered Gertrude Himmelfarb, also known as Bea, at a political meeting when they were both in college, and after a brief courtship entered into what their friend Daniel Bell described as "the best marriage of our generation." Theirs was a marriage of equals: Gertrude became a distinguished historian of British intellectual thought. They raised two children, one of whom — William Kristol — carries on his parents' work.

Later in life, Irving and Gertrude followed their children from New York to Washington, D.C. Reflecting on the move years later, he explained that "while New York intellectual and cultural life becomes ever more parochial and sterile — witness what is happening to the New York Times, which used to be a national newspaper — Washington inches along toward greater hospitality to the life of the mind." He was too modest to say how much their move contributed to that enlargement.

In Kristol, we have an intellectual very different from the European models of nonconformist or dissenter. The political scientist James Q. Wilson noted in an essay on Kristol that the most radical cultural division in all of history was "that between the attachment ordinary people have for the family and the hostility that intellectuals display toward it." That being the case, the example Kristol set of the fully integrated, familial intellectual may have been even greater than the sum of his ideas.

JOINING THE FRAY

Irving Kristol showed his mettle as a political thinker early on. His essay "'Civil Liberties,' 1952 — A Study in Confusion," published in Commentary when he was 32 years old, was to remain his most notorious. He wrote it following the public trials of Alger Hiss, who was accused of spying for the Soviet Union and convicted of perjury in connection with that charge, and of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were convicted of espionage in 1951.

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) had been founded in the 1930s to investigate both fascist and communist infiltration, but turned its focus exclusively toward the latter after the defeat of Nazism in the Second World War and the ensuing revelations of communist subversion. By the late 1940s, HUAC had extended its probe beyond those suspected of formal spying for Moscow and had begun to investigate those associated with the Communist Party. Once the entertainment industry and universities began blacklisting and firing people named at HUAC hearings, the sympathy of America's cultured elites came to favor the defendants. Senator Joseph McCarthy's prosecutorial overkill so damaged the credibility of the investigations that McCarthyism became a synonym for witch-hunting, and accusations of "Red Scare" tactics became an excuse for dismissing the dangers of actual subversion.

Kristol cut to the heart of the issue in his essay. "Do we defend our rights by protecting Communists?" he asked. He answered, emphatically, we do not:

Perhaps it is a calamitous error to believe that because a vulgar demagogue lashes out at both Communism and liberalism as identical, it is necessary to protect Communism in order to defend liberalism. This way of putting the matter will surely shock liberals, who are convinced that it is only they who truly understand Communism and who thoughtfully oppose it. They are nonetheless mistaken, and it is a mistake on which McCarthyism waxes fat. For there is one thing that the American people know about Senator McCarthy: he, like them, is unequivocally anti-Communist. About the spokesmen for American liberalism, they feel no such thing. And with some justification.

Those last sentences are probably the most widely quoted of Kristol's writings. In Kristol's view, liberals considered the "vulgar demagogue" a greater threat to American democracy than communism, which they treated as simply another political trend deserving of First Amendment space to make its case. The rest of the country, though, saw communism for what it was: "a movement guided by conspiracy and aiming at totalitarianism rather than merely another form of 'dissent.'" When faced with a choice between political evils, the American people wisely chose the lesser over the greater, which was more than could be said for New York liberals — who would never forgive Kristol for exposing their folly.

The reaction was even angrier than Kristol had anticipated. Liberals were prepared for an attack on the bad guys — the communists — but not an attack on themselves. They considered themselves the reasonable moderates between warring camps, and here they stood accused of betraying constitutional democracy for failing to oppose both totalitarian systems, fascism and communism alike. McCarthy may have been prepared to smear actual spies and mere dissenters with the same brush, but Kristol argued liberals did something even worse when they refused to discriminate between free thought and conspiratorial propaganda. As Kristol wrote, "The problem of fighting Communism while preserving civil liberties is no simple one, and there is no simple solution. A prerequisite for any solution, however, is, firstly, a proper understanding of Communism for what it is, and secondly, a sense of proportion [among different levels of sin and crime]." By insisting that the country must either embrace full civil liberties for everyone or disregard civil liberties entirely, liberals were putting democracy at risk.

Kristol's conservatism began by forcing liberals to confront an evil they did not want to acknowledge and a war they did not want to fight. The evils of fascism were on display in newsreels of the crematoria; he gave himself the harder task of unmasking the evil masquerading as an egalitarian ideal.

This shift of attention from Moscow to its liberal enablers was timely. By the 1950s, the Cold War between America and the Soviet Union was intensifying, and left-leaning factions within the academy, the media, and the intellectual elite were busily attacking American institutions and the very idea of the free world. Philip Selznick, a prominent sociologist and lifelong friend of Kristol's, described their response to some of these intellectual and political challenges in his 1995 essay "Irving Kristol's Moral Realism":

As we contemplated the moral ruin in the Soviet Union, and the responsibilities of Leninism [for that failure], we felt seared by the breath of evil. In response, we earnestly sought a better understanding of human nature, leadership, organization, and mass politics. We turned to writers in theology and social theory — Reinhold Niebuhr and Robert Michels, among others — for help in articulating a deeper appreciation for the dilemmas and frustrations of social idealism. Those writers helped us understand the irrepressible role of power and domination in human affairs; the tyranny of means over ends; the subversion of good intentions by unintended effects; the recalcitrance and frailty of people and institutions; above all, the insidious collusion of good and evil.

Kristol credited Niebuhr with having introduced him to "the idea of 'the human condition' as something permanent, inevitable, transcultural, transhistorical, a transcendent finitude. To entertain seriously such a vision is already to have disengaged oneself from a crucial progressive-liberal piety." He said it also enabled him to read the Book of Genesis with appreciation bordering on awe. By the late 1940s, his developing passion for religious thought affected his political priorities; as he reflected later, "It requires strength of character to act upon one's ideas; it requires no less strength of character to resist being seduced by them." The first priority of Judaism was to oppose idolatry: Kristol's intellectual task had shifted from coming up with good ideas to exposing the disastrous consequences of bad ones.

Kristol's response to the evolution of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was originally designed to eliminate all trace of discrimination on the basis of race, color, or creed, is one example. The ideal of equality before the law — a laudable goal, obviously in keeping with the founders' ideals — was shanghaied almost immediately by those who substituted the goal of equal outcomes for that of colorblind equal opportunity. Under the motto of "affirmative action," universities adopted a policy of group preferences in an effort to embrace "diversity." Kristol saw this penetration of quotas for what it was. As he wrote in Fortune magazine in 1974,

Who would ever have thought, twenty or even ten years ago, that we in the United States would live to see the day when a government agency would ask institutions of higher learning to take a racial census of their faculties, specifying the proportion of "Indo-Europeans" (traditionally, just another term for "Aryans")? And who could have anticipated that this would happen with little public controversy and with considerable support from the liberal community? How on earth did this fantastic situation come about?

The main foes of American constitutional democracy were no longer the Ku Klux Klan and neofascists, but elites practicing a novel form of discrimination. Claims about the unfairness of American life were being used to promote unfair practices. Kristol was particularly appalled that liberal Jews who had fought for the original civil-rights legislation did not see the danger of this inversion to themselves and, ultimately, to black Americans.

No less perverse was the liberal condemnation of economic disparity as the "original sin" of the American way of life. The classic version of the American dream taught that every child, whatever his starting circumstances, could with proper encouragement and strong character work his way up the socio-economic ladder. America was the promised land of opportunity. Yet egalitarians, channeling socialist ideas, recast the dream as a nightmare that allowed some to wax rich at the expense of the exploited poor. Americans would forfeit their freedom, Kristol wrote in "The Spiritual Roots of Capitalism and Socialism," if they did not re-learn the healthy connection between economic and political liberty. Capitalism's imperfections were vastly preferable to the tyranny of engineered perfection:

I know the question of equality is something that many religious people are quite obsessed with. Here I will simply plead my Jewishness and say, equality has never been a Jewish thing. Rich men are fine, poor men are fine, so long as they are decent human beings. I do not like equality. I do not like it in sports, in the arts, or in economics. I just don't like it in this world.

Kristol's composure, his playfulness even — so very different from the defensive or belligerent tone of today's polemics — show how freely he engaged in American politics as an identified Jew. He had not started out writing about politics from a Jewish perspective, but once he realized how much of his political thinking derived from Jewish experience, he also wrote about the concurrence of Jewish and American interests and values.

The political behavior of Jews similarly influenced Kristol's writings. In the above example, he applauds the traditional Jewish relation to capitalism. But elsewhere he calls modern Jews exemplars of "political stupidity," in part because of their failure to recognize that only by standing up for themselves could they benefit their country.

DEFINING NEOCONSERVATISM

Before being labeled a "neoconservative" by Michael Harrington — whose break from Catholicism had led through Trotskyism to atheistic socialism — Kristol had not indicated a wish to found a movement. (Harrington leveled the "charge" of neoconservative at Kristol for having moved in the opposite intellectual direction from himself.) But Kristol had the wit to realize that the term could be useful, and convinced others, including Commentary editor Norman Podhoretz, to adopt it favorably. He called it a "persuasion" — not to be mistaken for a competitive ideology.

The prefix was valuable in differentiating the "neos" from the nativists whose traditionalism was shaped by Christian culture, and sometimes included undesirable and outdated regional and class tendencies. Unlike the "paleo-conservatives," neocons had the intellectual advantage of having turned against ideas they had once embraced. Many of them were only one generation removed from Russia, where the Bolshevik takeover of that vast country proved how powerful ideas could be. Earlier Marxist revolutions in Europe had failed; the one in Russia succeeded, and to horrible effect. The neoconservatives knew that, though American democracy was far more resilient than tsarist authoritarianism, the Judeo-Christian foundations of America and Western civilization as a whole were no less at risk unless they could rely on the defense of better ideas.

Kristol and other neoconservatives sought to provide this defense. He believed that political ideas were essential not only to intellectuals but to the general public, and that they always helped to shape our political reality. In his autobiography, he argued that "[i]t is ideas that establish and define in men's minds the categories of the politically possible and the politically impossible, the desirable and the undesirable, the tolerable and the intolerable." He viewed the task of both the Talmud and the American Constitution, and that of intellectuals, as clearing a path through this minefield of alternatives.

Here we come to one of the ways in which Kristol is at his most original. As his expertise expanded from politics to economics, sociology, philosophy, history, anthropology, and beyond, he saw the way these subjects came together in rabbinic wisdom. Few other Jewish intellectuals prominently featured Jewishness in their work, and fewer still made it the culmination of their intellectual journey. Kristol was not a ba'al t'shuvah — a person who has returned to religious observance — but he did take up the serious study of Jewish ideas as an intellectual counterforce to the Old and New Left.

Gertrude Himmelfarb gives us a comprehensive description of her husband's thinking about these questions in her introduction to On Jews and Judaism, a posthumous collection of his essays on those themes. The Kristols were for a time members of a study circle at the Jewish Theological Seminary under the maverick thinker Jacob Taubes. A closer and stronger influence was Kristol's brother-in-law Milton Himmelfarb, director of research for the American Jewish Committee, editor of its American Jewish Yearbook, and a regular contributor to Commentary on Jewish subjects. The two men's political views sometimes read like the Jewish and general versions of the same ideas. Himmelfarb's law of Jewish politics — "Jews earn like Episcopalians but vote like Puerto Ricans" — defines Jews as a subset of Kristol's mugged liberals who refuse to learn from experience.

The conservatism of both men incorporates the pervasive "liberal" component in Talmudic thought. If they differed, it was because Himmelfarb was solidly centered in Jewish affairs whereas Kristol stood apart from Jewish communal concerns like intermarriage, the low Jewish birthrate, failing Jewish education, or the daily threat to the Jews of Israel. It was rather the steady search for wisdom and truth that brought Kristol, pace Spinoza, to the intellectual love of Judaism. He experienced Judaism as an American.

AN ALTERNATIVE TO COMMUNISM

Lionel Trilling's novel Middle of the Journey, which provided an indispensable study of the politics of his intellectual circle (which included Kristol), underscores the significance of Kristol's relationship with Judaism, albeit indirectly. The novel's main character, John Laskell, speaks for Trilling. A second character, Gifford Maxim, is based on the real-life Whittaker Chambers, who had run an underground spy network for the Soviets, defected out of moral revulsion at Soviet criminality, and sought the help of Trilling, his former Columbia University classmate, in resuming his life as a loyal U.S. citizen. The climax of the novel is a showdown between Laskell and Maxim (that is, Trilling and Chambers) over what happens after their disillusionment with communism.

Laskell's position is very much like the one Kristol took in his 1952 essay on civil liberties. He is first among his fellow liberal-leftists to admit that the Soviet Union really is as evil as Maxim claims, and he categorically rejects its claim to be serving humankind. But like everyone who breaks with the left, he must figure out where to go from there.

Like the real Chambers, Maxim became a devout Christian following his break with communism. In the novel, he explains that his "community with men is that we are children of God." The others think he has gone out of his mind. They cannot believe that anyone in their intellectual circle could turn to religion. They are ultimately less shaken by Maxim's revelations about the Soviet Union than by his emergence as a Christian believer. While Laskell, still speaking for Trilling, doesn't call him crazy, he, too, firmly opposes what he sees as an inadequate replacement for communism.

For Laskell, who "had been brought up without religious belief," the religious texts that resonate so deeply with Maxim "had no force of childhood reminiscence." This deficiency in Trilling's actual upbringing distinguishes him from Kristol, whose childhood attachment to Jewishness evolved into a mature and admiring relationship. In the novel, Laskell rejects Maxim's religion. He treats the move from communism to Christianity as merely the exchange of one hermetic system for another, and, as the truer intellectual, he stays clear of both. In Laskell, Trilling creates an unaffiliated American with no ethnic or religious identity. And since religious faith is represented by Maxim's Christianity, and Christianity is treated as merely a substitute for communism, Trilling may have felt that he was being something of a Jew in repudiating religion outright.

Though Kristol called Trilling one of his intellectual godfathers, he thought very differently on this subject. Had he been allowed to speak in the novel, he would have joined Maxim in embracing religion, and opposed communism from an intrinsically Jewish perspective. He feared the Christian believer much less than he did Trilling's post-Christian liberal who purged the essential element of the country forged "under God." He believed intellectuals did America an injustice when they tried to edit out Christianity from the Judeo-Christian basis of the Constitution. To Kristol, Jews not only betrayed their own religious civilization but also damaged the country when they opposed religion in the public square.

Indeed, Kristol saw that, for the believer, religion could inform one's views of capitalism and the American system itself, insofar as it informs one's ideas about the nature of man and of society. Kristol directly addressed his views on Christianity, Judaism, and socialism in a speech to a conference of theologians in 1979. In that address, he explained his "nonpracticing — or nonobservant" adherence to the spirit of orthodoxy:

When I talk about religion, I talk as an insider, but when I talk about Christianity, I think it will be very clear that I talk as an outsider. When I say I am not a Christian, I do not say it polemically, of course. But whether one is Jewish or Christian does, it seems to me, affect one's attitude toward capitalism.

While Kristol aligned Christianity and Judaism against their secular socialist challengers, he also offered some fine distinctions between the two religions — particularly between Orthodox (or rabbinic) Judaism and Christianity — in their attitudes on commerce and capitalism. For one thing, Kristol suggested that "Orthodox Jews have never despised business; Christians have. The act of commerce, the existence of a commercial society, has always been a problem for Christians." He argued that "[g]etting rich has never been regarded as being in any way sinful, degrading, or morally dubious within the Jewish religion, so long as such wealth is acquired legally and used responsibly." Judaism's goal of fulfilling human potential to the utmost must include making a living.

This attitude is part of Jewish moral realism, which tries to build a good society for human beings as they are. The reason for supporting capitalism is that so far it has proved the best economic system for fulfilling human potential to the utmost. That is likewise why America is a capitalist country. Understood in this way, religion is central to America, but between rabbinic Judaism and Christianity, the former's attitude toward success is better suited to America's political nature.

For Kristol, the economic behavior of many Jews was part of a larger issue: "We are talking about an eternal debate about the nature of reality, about the nature of human authenticity," a debate between those making the best of the world as it is and those engaged in "metaphysical rebellion," who wish to liberate us from the prison of this world. That tension exists within all religions — Judaism included — and extends into secular modernity. "Orthodoxy" is Kristol's term for a moral realism that tries "to give answers to questions that are unanswerable, that is, questions of why we live in a world that is 'unfair.'"

In his search to explain this eternal tension, Kristol refers back to gnosticism, a movement that emerged from Christian and Jewish sources at their point of intersection in the second century. The gnostics — somewhat like kabbalists among the Jews — believe that the material world is a debased result of the divine spark having fallen into a lower state, and that ideal human potential must be released from it. Crudely stated, they view matter as evil, and the realm of spirit as good. In Judaism this is only a sectarian position. But the redemptive impulse plays a much larger role in Christianity, and it assumes a dominant role in socialism, which transposes the ideal of transcending human error into economic terms. Once Jews cease to follow the Orthodox Jewish way of life, they become exceedingly susceptible to the progressivist temptation in secular politics.

Though I do not think the gnostic terminology serves Kristol particularly well, the gist of his analysis is firm and unerring. The same impatience with rabbinic Judaism that animated early Christians is felt by modern Jews who wish to "repair the world" in some way that does not entail following the commandments. Kristol understands the appeal. As against the growing atomization of modern society, these movements offer a sense of community. As compared with the apparent selfishness of capitalism that concentrates on individual material well-being, these movements aspire to help the needy, and to inspire in their adherents a sense of virtue. But when all is said and done, the rabbinic attitude is true to human nature.

The type of falsehood embedded in the socialism embraced by liberal Jews, he believed, would end in tyranny. He saw older forms of tyranny — led by Roman emperors, European monarchs, or Russian tzars — being replaced by an egalitarian tyranny that would force its own idea of perfection on societies that could never meet its standards. He feared that, if left unchecked, it might destroy the rough balance that rabbinic Judaism and American constitutional democracy have achieved. One can see why Kristol found "neoconservatism" such a convenient term for the set of political ideas he had teased out from a religious source.

AN UNCOMMON INTELLECTUAL

William F. Buckley gave American democracy his vote of confidence when he said he would rather be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Boston telephone directory than by the Harvard University faculty. Irving Kristol felt similarly; as he wrote in 1983, "It is the self-imposed assignment of neoconservatives to explain to the American people why they are right, and to intellectuals why they are wrong."

Likewise, Leo Strauss challenged the philosophical assumptions of progress and questioned whether standing on the shoulders of giants really meant that you saw any further than they did. He, too, drew from the conservative roots of Judaism in his 1962 lecture, "Why We Remain Jews," and concluded that "[t]he Jewish people and their fate are the living witness for the absence of redemption. This, one could say, is the meaning of the chosen people; the Jews are chosen to prove the absence of redemption." Some would call this an outrageously bleak interpretation of the Jewish role in history, but Strauss did not intend it pessimistically. Proving the absence of redemption required demonstrating over thousands of years the stamina for creative survival.

This was Kristol's view, though he expressed it in a matter-of-fact American style rather than in majestic philosophic terms. Kristol had always felt at home in America — more precisely, everywhere at home with himself — but his own youthful flirtation with communism made him constantly aware of how vulnerable the country was to the destructive potential of well-intentioned enthusiasts.

In many ways, he was an intellectual spokesman for the American people; Michael Joyce called him "the common man's uncommon intellectual." Unlike so many of his intellectual peers, his thinking was never hostile to religion or resentful of family life, which gave him the advantage of better understanding his fellow man. His rabbinic approach to intellectual life gave him insight into human nature and allowed him to see the danger in the best-laid technocratic plans. Kristol believed it was incumbent upon American intellectuals — and maybe especially upon the Jews among them — to conserve the good in their country before attempting to perfect it. We would be wise to follow his example by approaching big ideas for reform with humor and humility.