Franklin and the Free Press

Many Americans today have an ambivalent stance toward the free press. On the one hand, nearly all citizens assent to the idealism that originally justified its creation: We value the discovery and circulation of the truth, and the prevention of governmental tyranny. As such, the press is meant to serve both intellectual and political liberty. Yet, on the other hand, few citizens directly experience this idealism, feeling instead the press's forcefulness, flattery, vehemence, and sometimes fanaticism — often akin to warfare directed at their minds and sentiments. Rather than heading off intellectual and political dogma, the press often creates or disseminates it. A great disparity thus exists between the press's ideals and its practice today.

As originally understood by many of America's founders, the open circulation of the truth through the press would serve both society and the individual. As Thomas Jefferson explains,

No experiment can be more interesting than that we are now trying, and which we trust will end in establishing the fact, that man may be governed by reason and truth. Our first object should therefore be, to leave open to him all the avenues to truth. The most effectual hitherto found, is the freedom of the press.

In addition, many of America's founders also understood the press as an essential bulwark against government for the securing of individual rights. Jefferson, again, summarizes:

I am...for freedom of the press, and against all violations of the constitution to silence by force and not by reason the complaints or criticisms, just or unjust, of our citizens against the conduct of their agents.

The press, and especially the mass press, is a means by which to enforce accountability and responsibility in the government, and to thereby compel government's virtue. Moreover, newspapers even help "maintain civilization," as Alexis de Tocqueville observes in Democracy in America. By giving democratic citizens common opinions, common sympathies, and a resource for common action, newspapers can help prevent the individuation and isolation of citizens to which democracy disposes them.

These idealistic aims markedly diverge from the mass press's actual behavior and its effects on republicanism. And that is not a new problem. During America's founding, as historian Leonard Levy observes, an "extraordinary partisanship, vitality, and invective had become ordinary" in the press. Indeed, today's press has similar inclinations, often imposing onto the public its taste for derision and ridicule, which it substitutes for depth and thoughtfulness. Examples abound, but consider the Huffington Post's editor's note, added to nearly every article referencing Donald Trump during the 2016 election:

Donald Trump regularly incites political violence and is a serial liar, rampant xenophobe, racist, misogynist and birther who has repeatedly pledged to ban all Muslims — 1.6 billion members of an entire religion — from entering the U.S.

Not stopping at public figures, the press also satisfies its penchant for crushing the will of private citizens and groups through shame and fear, making them feel their smallness and brittleness. Its behavior, in sum, often discloses the press's tacit opinion concerning America's moral hierarchy: that the press is not merely a fourth estate, but the judge of would-be rulers, and therefore the master, or at least the kingmaker. Yet it remains unclear whether the press rules with the spirit of humanity and prudence, or whether it is animated by the desire to dominate the public mind. It frequently vacillates between these extremes.

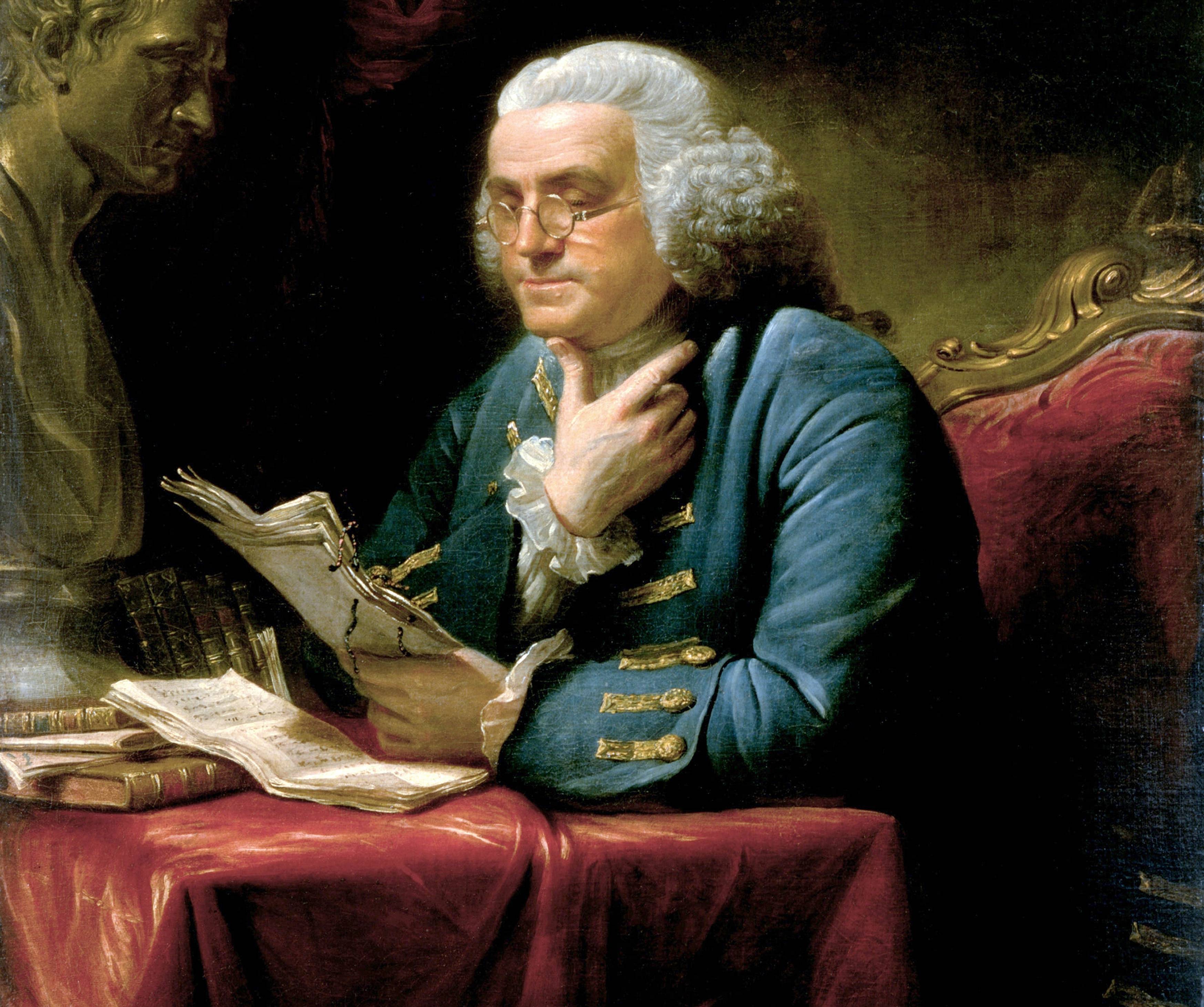

By contrast to the early Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin had no illusions about the character of the press in America. Few serious thinkers have reflected with as much clarity on the nature of the press as Franklin. And no other thinker has had so much experience and commercial success in it. A lifelong defender of the freedom of the press, Franklin was nevertheless not uncritical of its effects.

Franklin's short but rich essay, "An Account of the Supremest Court of Judicature in Pennsylvania, viz., The Court of the Press," written a year before his death in 1790, lays out a comprehensive analysis of the press: its effects on politics and the democratic mind, its mode of rule, and the origins of its power. His study is, in a sense, an examination of the effectual truth of the principle underlying freedom of the press. His reflections are urgently needed today.

The press, Franklin argues, unlike any other republican institution, has a power that does not fall under any constitutional check. It is motivated to act viciously by its very principle (created to attack dogma, false knowledge, and political corruption), though in practice it is neither limited nor moderated by either its own idealism or by any institution. While the press claims to rule like a court — passing all things before its judgment — it may rule tyrannically because it is liberated from considerations of justice or precedent. Thus unchecked, the press can subvert rational habits of mind among citizens and reverence for the law while flattering public resentments and antagonizing citizens' pride. Franklin was consciously witnessing the birth of a new class, a kind of press corps, created by this new principle, and his assessment of the human content of this class is contrasted with the powers it wields. For Franklin, a free press must be checked by a vigilant and jealous public, which he hopes to energize against abuses of liberty.

Franklin's literary style differs from that of the other founders. As University of Chicago professor Ralph Lerner has observed, Franklin often "works on us through indirection and insinuation. But he leaves it to us to catch his drift." In his analysis of the press, Franklin tacitly points out both the problems with our idealism (so as to soften their deleterious effects) and the conflicts in our motives and hopes (so as to encourage a liberating skepticism). He does so with a view to protecting democratic self-respect while exposing and ridiculing the ability of the press to undermine the host democracy's institutions.

POWER AND SUBVERSION

In order to get at Franklin's perspective on the press in America, we need to take a step back to get a sense of its powers. According to Franklin, the press's powers resemble those of a "court," a term he uses in several ways. In the first sense, the press resembles a conventional court of law: It has the power to "judge, sentence, and condemn to infamy" citizens both public and private. The press even carries out court-like powers by conducting what look like hearings and inquiries. And since in a republic none can claim superiority to the law, "all persons" and "all inferior courts" are subject to its jurisdiction and judgment. In this way, the press claims to imitate the majesty, objectivity, and moral authority of a court of law.

The press does these things, however, without being "governed by any of the rules of common courts of law." Unlike a legal court, the press is not part of the judicial system and is therefore not subject to the institutional checks that moderate political power and authority. While the claims to equity and justice authorize such powers in a court of law, the press is neither restrained by legal precedent nor by evidentiary standards that assure the maintenance of those claims. Thus, for example, rather than relying on witnesses sworn to truthfulness, it may use anonymous sources, who suffer no consequences for dishonesty. In fact, as it often rules through mere "accusation," no limits seem to exist on the nature or extent of the accusations, just as there are no limits on who can be accused.

The press's proceedings occur "with or without inquiry or hearing, at the court's discretion" (emphasis in original). The press acts on its own initiative, rather than through citizen or executive complaint. It can pick and choose its own cases — selectively closing its eyes to some, while opening them to others — not with a view to satisfying justice or the law, but in accordance with its own prejudices or interests. Since the press follows its own discretion, its operations and methods are not fully knowable, and one therefore cannot appeal to it rationally. The press is conscious of this supremacy, Franklin contends.

The press also resembles a religious court, Franklin half-jokes, the "Spanish Court of Inquisition," in its moral authority to force and shape belief through fear and intimidation. Like the Spanish Inquisition, the press enforces its pre-eminence by reaching into individual souls and compelling belief. When the press acts against individuals and institutions:

The accused is allowed no grand jury to judge of the truth of the accusation before it is publicly made, nor is the Name of the Accuser made known to him, nor has he an Opportunity of confronting the Witnesses against him; for they are kept in the dark, as in the Spanish Court of Inquisition.

The open presentation of evidence of wrongdoing corroborated by facts shows respect for rational and transparent procedures that embody the spirit of justice. Such proceedings presume citizens' intellectual capacity to be convinced by the force of facts and arguments. With the Inquisition, to the contrary, assent is founded on fear and intimidation, as one would expect from despotism. Here there is darkness, mystery, and anxious anticipation. In its practice, Franklin contends, the press contradicts the principles by which it justifies its authority: It claims that belief stems from the free and rational persuasion of the mind, but in its deeds it insists that belief should be compelled through its own powers of insinuation, intimidation, and accusation.

The press has a despotic inclination for making citizens experience its overwhelming power: It takes an "honest" and "good" citizen who, through what is almost a miraculous transformation, "in the same Morning" is judged and condemned by the press to be a "Rogue and a Villain" (emphasis in the original). Its rapidity and forcefulness appear to be almost irresistible. Though the press does not burn individuals at the stake, nonetheless, like tribunals of the Spanish Inquisition, Franklin sees in the press the capacity for fanaticism originating in complete confidence in its ability to judge.

This unrestrained power can even willfully direct public opinion against the law itself, perhaps despite the public's interests. We witness one contemporary example of this power. Whatever one's view of immigration policy might be, the press, by relentlessly calling "illegal aliens" "undocumented immigrants" for years, has subtly altered public sympathies against would-be enforcers of the law. The press can make the law appear weak and its authority questionable in comparison to its own power.

Although prepared to subvert the law at times, the press relies on the law's protection when using it for its own advantages:

[I]f an officer of this court receives the slightest check for misconduct in this his office, he claims immediately the rights of a free citizen by the constitution, and demands to know his accuser, to confront the witnesses, and to have a fair trial by a jury of his peers.

In sum, the press sometimes reveres and sometimes subverts the law; sometimes it guides public opinion toward the law, sometimes against it. But the press always seems to know its interest in maintaining its superiority over the public mind.

SUPERIORITY AND MEDIOCRITY

Franklin asks us to contrast this remarkable power with the character of the members of the class wielding it. The freedom of the press creates a new human type that dominates the liberal-democratic landscape to this day. This new type is "appointed to this great Trust" of guiding the public intellect, deciding upon citizens' fates, and sometimes even determining the future of the nation.

This new class, Franklin notes, is open to anyone. The officers of the press corps are not appointed by an executive authority on the basis of their virtue. Nor is the press a hereditary institution governed by and therefore subordinated to considerations of honor or tradition. (Franklin is not in favor of such alternatives, of course.) As such, he observes that under the new democratic conditions, this class is self-created, so to speak:

[A]ny Man who can procure Pen, Ink, and Paper, with a Press, and a huge pair of Blacking Balls, may commissionate himself; and his court is immediately established in the plenary Possession and exercise of its rights.

The effect of this, for Franklin, is the creation of a class requiring neither "Ability, Integrity, [nor] Knowledge." Surely these qualities sometimes exist — look at Franklin! — but just as surely they are not necessary prerequisites. Franklin chooses his words carefully, subtly leading us to ask whether, in practice, these virtues often become their opposites: Sensationalism will often be mistaken for ability, contempt for all those inferior to it mistaken for integrity, and pedantry mistaken for knowledge. Franklin suggests that the public mind may come to imitate this confusion of virtue and vice under the press's influence.

This class of unelected opinion makers is also unified by a specific motive, Franklin contends. It is a community that shares the "privilege of accusing and abusing the other four hundred and ninety-nine parts at their pleasure." These numbers are invented, of course, but Franklin is pointing to the hidden motive unifying this community — the mutual indulgence in feigned superiority, the pleasure of punishing, and a taste for contempt for one's fellow citizens and for would-be rulers. Can one serve the public if one has contempt for it?

Furthermore, Franklin observes that the powers granted to the press, through the principle authorizing its existence, often culminate in the appearance of principled courage. Feeling its superiority to individual citizens or other public institutions, the press rebels against inquiries into its authority and the modes of its rule: "For, if you make the least complaint of the judge's conduct, he daubs his blacking balls in your face wherever he meets you." What at first glance may seem like dignified courage in carrying out its duties is perhaps merely the protection of its own superiority coupled with vengeance against those questioning it.

Indeed, the press, Franklin argues, may use its capacity to "[mark] you out for the odium of the public, as an enemy to the liberty of the press," in order to suppress dissent against its authority. This has the effect of crushing the voice of reason in citizens along with the self-confidence necessary for them to voice their thoughts publicly. Franklin tacitly suggests that, over time, citizens may lose their habits of reason through this kind of rule.

One barely needs to add that this class serves for its own "Emolument." Franklin draws our attention to a dual unity in motive: Satisfying the pleasures of ruling citizens and indulging its own taste for contempt become financially lucrative under these new democratic circumstances. In an era of egalitarianism, most human beings are born without genuine wealth, the security of inherited social class and standing, or special destiny. Individuals therefore to a greater extent than ever before become their professions.

It's important to point out that during Franklin's time, owners of printing presses printed all kinds of things for profit: newspapers, books, and pamphlets, encompassing every subject, sometimes including the printing of the libelous and scurrilous as well. Our newspapers no longer do precisely this, of course (though it is subject to debate whether appearing to praise oneself for alleged objectivity, as newspapers do today, while printing what is essentially partisan, has polluted the moral and intellectual waters more than when, as during Franklin's time, all citizens knew that the press was for hire). Nevertheless, the problem Franklin draws our attention to is still with us. When intermixed with the self-serving powers to command public opinion, merely aspiring to uphold a principle for one's livelihood rarely results in independence of mind or judgment. In fact, the appearance of acting on principle can be lucrative.

As Franklin makes clear, it is not entirely obvious whether the press's belief in its guiding principles is sincere, as it does not apply them equally to all other individuals or institutions. Today, for example, much of the press class is in favor of campaign-finance laws that regulate the expression of candidates, parties, and interest groups, but is uninterested in applying similar regulations to itself. Taken to its logical extreme, this may suggest that this class has a secret motive, aiming to limit free speech by making only its own speech acceptable. Its unwillingness to subject itself to the same standards of law and regulations as other authorities is suspect.

HUMAN WEAKNESS

Franklin also sees in the press a tendency to deform and undermine the idealism necessary for republicanism. Republicanism presumes that citizens are willing, at times, to sacrifice a great deal for liberty, like the signers of the Declaration of Independence who mutually pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor. Yet it is difficult to love liberty if it is experienced as moral chaos, which the press can infuse into democratic life. In fact, Franklin fears that political liberty, as redefined by the press, may come to mean the "Liberty of affronting, calumniating, and defaming one another." In such an environment, liberty may come to be experienced as burdensome, tedious, and ugly, encouraging citizens to "cheerfully consent to exchange [their] Liberty of Abusing others for the Privilege of not being abus'd [themselves]."

In theory, the freedom of the press presumes that what is most crucially common to all human beings is each individual's rational faculty, on the basis of which modern republicanism is created and defended. Thus, for Franklin, among the highest manifestations of the freedom of the press is the "Liberty of discussing the Propriety of Public Measures and political opinions." By this definition, he seems to mean the publication of works like the Federalist Papers (which appeared as a series of newspaper columns) or his own writings — though he is of course aware that this standard is rarely achieved in practice. Such writings elevate and deepen citizens. One should contrast Franklin's understanding to the recently developed public view of speech which considers dignified any spasmodic effusion of half-formed feeling, obscenity, or agitation subversive of republicanism.

These powers to abuse rather than bolster republican idealism and rational habits of character, Franklin contends, find their "natural Support" in human resentment. Resentment, a "depravity" of the human character, is a powerful though hidden source of the press's power over the mind. Franklin quotes Juvenal's Satires to explain:

There is a Lust in Man no Charm can tame,

Of loudly publishing his Neighbour's Shame.

On Eagle's Wings immortal Scandals fly,

While virtuous Actions are but born and die.

Resentment is an ugly, double-sided passion. It leads one to assert moral superiority over others, thereby demanding superior desert for oneself, while simultaneously desiring that harm befall others so as to protect one's own inflated self-appraisal. As Franklin politely puts it, "Whoever feels pain in hearing a good character of his neighbour, will feel a pleasure in the reverse." Resentment does not even depend on one's own faring well, for one can be resentful and at the same time prosperous.

Franklin is being neither flippant nor pedantic regarding the central importance of resentment. He is pointing to the deeper problem which resentment reveals — human confusion about desert. As Jerry Weinberger has argued in Benjamin Franklin Unmasked, among the central premises of Franklin's philosophical thought is that human beings want more for themselves than they deserve. This desire deludes our judgment, distorts our opinion of ourselves, and to a great extent accounts for the human comedy of errors. It also accounts for our jealous hatred of others' success.

This passion, in conflict with republicanism, is flattered by the press, Franklin argues. In amplifying and dignifying resentment, the press cultivates its own popularity and reach. There are always many "who, despairing to rise into distinction by their virtues, are happy if others can be depressed to a level with themselves." In flattering the public's resentment, the press blinds it to its own mediocrity, Franklin suggests. Today, this psychology follows a predictable pattern: tacitly or overtly belittling or ridiculing human greatness, cutting it down to a digestible size, while exposing and laughing at private vices — or, alternatively, encouraging indulgence in feigned great moral feeling without the requirement of sacrifice or sincerity. The steady stream of examples of baseness, greed, and dishonesty teach the lesson that such individuals are no better than you — in fact, they are worse, because you can look down upon them. By implicitly calling resentment high-mindedness in flattering its audience, the press often both ridicules virtue and avoids making mediocrity appear contemptible.

Franklin sees the formation of a community of mutual flattery between the press's desire to rule and the public's resentment. On the one hand, fostering resentments maintains the press's power over the public — for in satisfying the public in such a way, it is allowed to govern the public's tastes and passions. And the public, on the other hand, in showing its gratitude for not being targeted or undone by the press, redoubles rewards by showing obliging subordination.

Thus, in a final sense of the press's playing the role of a "court," it is akin to a monarchical court, for it serves a monarch — the public. Yet in serving its monarch, does the press play the role of the French revolutionary, re-enacting the guillotine by beheading individuals or institutions in order to satisfy the public's resentments? Oddly, the press, originally conceived as an essential means by which to preserve political and intellectual freedom, may become a mechanism through which the public oppresses itself. In suggesting that the lust to satisfy resentment guides "such minds, as have not been mended by religion, nor improved by good education," Franklin is goading us to consider more closely the kind of education he is providing his readers, which can correct this natural defect. His wit makes us aware of our defects, while his humor attempts to shame us out of them.

LIBERTY OF PRIDE AND HONOR

Is it possible to correct for these abuses of the free press? Unlike the other powers enumerated in the Constitution, Franklin observes that the press has no corresponding check against it:

[S]o much has been written and published on the federal Constitution, and the necessity of checks in all other parts of good government has been so clearly and learnedly explained, I find myself so far enlightened as to suspect some check may be proper in this part also; but I have been at a loss to imagine any that may not be construed an infringement of the sacred liberty of the press.

Franklin jokes that the only check he can find is the "liberty of the cudgel." In other words, the press is free to print as it pleases so long as citizens are free to go to an authentic offender "and break his head." Franklin's ludicrous solution points to a contradiction in republican laws.

Self-government presumes a certain measure of self-respect and pride among citizens. Republicanism depends on the conviction that individuals have the psychological and physical ability to order their lives and to legislate for themselves and their community on the basis of their judgment.

Individual pride, of course, cannot be given full reign in a republic, nor can its demands be fully satisfied. When carried to its extremes, pride points to absurd self-importance and tyranny. In republics, individual pride must be restrained to some degree for the protection of others' rights, for too much of it can destroy a republic. Yet republican law puts man in an odd state: On the one hand, man desires the full security of his pride and therefore his reputation — loving his reputation perhaps more than his life, as Franklin observes — while the law constrains his ability to defend it fully against its attackers. Defending one's self-respect, Franklin implies, is perhaps a right as much as any other. On the other hand, however, "the right [of the press] of abusing seems to remain in full force, the laws made against it being rendered ineffectual by the liberty of the press" (emphasis in original). Citizens cannot fully protect their self-respect while the press is given broad authorization to abuse it. For Franklin, the effect of this may be the weakening of citizens' pride and the diminishing of their attachment to self-government, which correspondingly grows the space for the press's influence over the mind.

What is to be done, according to Franklin? He jokes, "[L]eave the liberty of the press untouched, to be exercised in its full extent, force, and vigor; but to permit the liberty of the cudgel to go with it pari passu" (emphasis in the original). Franklin wants the vindication of republican pride — not just because he honors such sentiments, but because he thinks that such a counterbalance or check, like the checks employed in other parts of the Constitution, is necessary against the press's powers, too. In fact, the public can unite if it is affronted, "as it ought to be," by the press's abuses (emphasis in original). The public can show its "moderation," he jokes, by "tarring and feathering, and tossing them in a blanket." Franklin is of course not advocating such actions, but he does want the public to recall its power to humiliate.

Franklin concludes by emphasizing the need to secure citizens' reputations:

If, however, it should be thought that this proposal of mine may disturb the public peace, I would then humbly recommend to our legislators to take up the consideration of both liberties, that of the press, and that of the cudgel, and by an explicit law mark their extent and limits; and, at the same time that they secure the person of a citizen from assaults, they would likewise provide for the security of his reputation.

Balancing both liberties, for Franklin, ought to be among the highest considerations of legislators and statesmen — the liberty of the press and the liberty to defend one's pride. One wonders whether Franklin here explicitly means only libel laws, or is also referring to citizens who are jealous of their liberty and who know their power.

OUR PRESS

The press exists as an institution to protect and strengthen republicanism, resting on the idea that human beings and public institutions must be made good, or, as we say today, made responsible. But the press can also exceed its limits, becoming over-powerful and therefore no longer serving the interests of the society that hosts it. Franklin's solutions to the problems created by the press are partly comical, both because they are exaggerated and because relatively little, it seems, can be done about the effectual truth of this principle.

To some degree, the conservative oppositional press begun a few generations ago has addressed what is among the worst diseases of a republic: the centralization of the press. As Tocqueville observes:

When a large number of organs of the press come to advance along the same track, their influence becomes almost irresistible in the long term, and public opinion, struck always from the same side, ends by yielding under their blows.

The press's powers (as analyzed by Franklin), combined with centralization, may be lethal to a republic. In this regard, America's conservative oppositional press — which has no parallel anywhere else in the Western world — has greatly contributed to breaking up centralization. Yet having guided us away from the shoal of centralization, the oppositional press has created new problems.

With the help of new media technologies, the oppositional press has ushered into existence the parallel universes that American citizens now construct for themselves by choosing which press better flatters their prejudices. Alarmingly, citizens who inhabit each of these monolithic realities are more than merely at partisan ends of a political spectrum — they have become to some degree almost different kinds of beings, given the extent of their differences in sentiments, passions, habits of character, and tastes. Indeed, the new multiplicity of news sources, despite some obviously healthy effects, can create a greater and greater cacophony of similar sentiments while reducing genuine thoughtfulness. This need not, however, be our nation's final situation.

The quality of our press will decide the fate of our civilization. We might try to follow Franklin's general lessons in order to facilitate public discourse: bolstering citizen pride as a means of preventing the press's excesses; diminishing the public's resentment by ridiculing rather than flattering it; all while recalling that the press must serve republicanism rather than weaken it. For this to be possible, the press must renew its self-understanding. And the public ought to demand it. On the side of the press, this would mean a new devotion to elevating political debate — while consciously avoiding self-flattery, dogmatism, and partisan dishonesty — about important political questions facing the nation. On the side of the public, this means deepening its understanding of the stakes to the nation, and showing a new willingness to speak freely and rationally, despite the obstacles of political correctness or fear of intimidation.

Finally, lessons in moderating the press's power and reach may be seen in Franklin's own activity. Perhaps lampooning and parodying the press — that is, exposing it, its inferior personages, and its interests, through film, books, and on stage, as Franklin himself did — can liberate the democratic mind to some degree from its power. Also following Franklin, we see that democratic resentment — though exploited by the press — can be harnessed and directed toward useful ends. For example, resentment can despise and envy the great, or it can satisfy itself through the prosecution of corruption, both governmental and that of the press itself.