Elites and the Economy

There is a story we often tell ourselves about the modern American economy. The story is in part a tragedy, a tale of those left behind, and it has heroes and villains. The heroes are American workers, particularly industrial workers, who have found themselves facing ever-greater obstacles to prosperity and flourishing. The villains are the elites — wealthy corporate leaders and politicians who have rigged the system and manipulated the rules for their own benefit at the expense of those workers.

There are right-wing and left-wing versions of this story. In 2013, for instance, then-president Barack Obama argued that the American economy once more or less worked for everyone. "But over time, that engine began to stall," he said, and "that bargain began to fray....And so what happened was that the link between higher productivity and people's wages and salaries was broken. It used to be that, as companies did better, as profits went higher, workers also got a better deal. And that started changing." His implication was plain: that corporate leaders were depriving workers of their due wages in order to pad profits.

In 2019, the populist conservative television host Tucker Carlson offered a version of this story more at home on the right. In this telling, what has been lost is people's capacity to flourish and be happy, and the people at fault are both the rich in our economy and the powerful in our politics. Carlson said:

There are a lot of ingredients in being happy: Dignity. Purpose. Self-control. Independence. Above all, deep relationships with other people. Those are the things that you want for your children. They're what our leaders should want for us, and would want if they cared. But our leaders don't care. We are ruled by mercenaries who feel no long-term obligation to the people they rule.

Both forms of this narrative seem likely to be very prominent in the 2020 presidential race. On the left, we already find presidential candidates talking in terms of "corruption" and "concentrated power" to describe an economy "rigged" against the many, such that workers are not being fairly compensated for what they produce. Mainstream Democratic politicians seem to have determined that the market, managed by elites, is failing in many critical dimensions and that sweeping government intervention is needed to deliver better outcomes — not just to compensate for what the market hasn't given workers but to change the way the market distributes its bounty.

As for the right, President Trump's takeover of the Republican Party and his ambivalence toward key traditional conservative principles (such as free trade and limited government) has created an ideological vacuum. Although the debate within conservative circles is lively, diverse, and by no means settled, the loudest voices rushing in to fill the void tout economic populism. A critical dimension of this narrative, like the progressive diagnosis, is that elites are responsible for our woes. The right-of-center permutation of this view specifically holds that misguided policymakers, obsessed with abstractions like "GDP" and "consumption," have allowed markets to run amok, which in turn decimated the working class and propped up the wealthy and our foreign competitors. Proponents of these views insist that the free market is merely a tool — a means that should not be mistaken for an end — and that if left in the wrong hands, market power is no less dangerous than government power.

Both forms of this critique make some important observations, particularly about the tradeoffs between equity and efficiency. But both also seriously misdiagnose what ails us. Rather than corporate greed suddenly disconnecting one's ability to earn from one's ability to produce, or decades of gross negligence (or worse) by policymakers finally catching up with us, it is far more likely that American economic life has been changing in ways that were difficult to anticipate and hard to respond to. The economy has undergone massive shifts over the last several decades. The opening of new markets exposed domestic workers to fierce competition and increased the returns to scale and management. The evolution of the product cycle contributed to the hollowing out of established industries. A decades-long shift from goods production to service provision changed the allocation and intensity of capital investment. New technologies increased the returns to education and disrupted established occupations. The shifting nature and intensification of competition begat the rise of a "winner take most" model and "superstar" firms. And a rising dispersion of productivity across firms and the slowing diffusion of innovation altered the competitive landscape for businesses.

All of these factors have changed the nature of work and the returns to different skillsets in ways that policymakers didn't anticipate and that have wrought all sorts of other complications down the line. These things didn't happen by themselves; public policy makes a difference, and markets are the sums of human choices. But that does not mean that these developments have been a function of some elite-engineered scheme to rig the economy against workers.

The notion that every economic development is the intentional result of some elite agenda makes it impossible to think clearly about America's socio-political circumstances and to think creatively about solutions to the problems Americans face. The idea that these problems exist because someone with power wants them to exist is not sophisticated or worldly; it is naïve. It has too low an opinion of what elites in our society want, and too high an opinion of what they have the power to do. And it is eager to accept every dark assessment of socioeconomic conditions in America while rejecting any sign of progress or prosperity. The resulting rhetoric, which increasingly dominates both sides of our political arena, is inadequate to the challenges we face. But there is a way forward.

INEQUALITY OF PRODUCTIVITY

To begin, it is important to consider whether the core claims behind such rhetoric are accurate. The fundamental empirical assertion undergirding the policy agenda of progressive politicians, epitomized by President Obama's quote above, is that in the modern era pay and productivity have become disconnected as corporations withhold wages to pad profits.

This sentiment is remarkably pervasive. For example, in 2015 then-presidential candidate Hillary Clinton stated that "[y]ou're working harder but your wages aren't going up....That bargain has eroded. Our job is to make it strong again." And she backed up this claim with a chart showing divergent pay and productivity. In 2018, while launching her "Accountable Capitalism Act," Senator Elizabeth Warren said, "There's a fundamental problem with our economy. For decades, American workers have helped create record corporate profits but have seen their wages hardly budge." Further examples abound.

This is a powerful accusation. As Michael Strain of the American Enterprise Institute observes, not only does a linkage between pay and productivity have "attractive moral properties," economic theory tells us that firms are supposed to pay their workers what they are worth, so that their wage rate should equal their marginal revenue product.

This isn't just some textbook theory that's never been proven in practice. Even John Maynard Keynes, no doctrinaire conservative, famously remarked in 1939 that the stability of the relationship between output and compensation is one of the "best-established facts in the whole range of economic statistics" and is "a bit of a miracle." The stability of the relationship was famously enshrined in 1961 by economist Nicholas Kaldor as one of the few "stylized facts" of economics. Of course, other factors matter too, such as collective-bargaining arrangements or the tightness of the labor market, but productivity is widely regarded as the predominant factor explaining the variation in pay.

Against this backdrop, it would be both immoral and economically abnormal for firms to systematically not pay their workers for what they produce. If true, a decades-long de-linkage should be worrisome to defenders of our economic system.

As a practical matter, the accusation takes two forms. The first charge often leveled by politicians is that there was a sudden de-linking of the two starting around 1973. More specifically, the claim is that the productivity (defined as output per hour) of the average worker continued to rise while the pay (defined as compensation per hour) of the same average worker no longer increased commensurately. In this narrative, the timing of the de-linking is especially important because it occurs concomitantly with the rise of shareholder-value theory and neoliberalism.

This assertion of a decades-long de-linking has, however, been challenged by a number of researchers including analysts at the Congressional Budget Office (in 2006), James Sherk (in 2013 and 2016), Scott Winship (in 2014), Robert Lawrence (in 2015), and Anna Stansbury and Lawrence Summers (in 2018). Those researchers conclude that, when measured properly, average pay and productivity either move together or at least move in a way that is statistically indistinguishable from a one-to-one relationship over time.

The second line of argument asserts that rising productivity no longer really benefits the middle class. For example, Jared Bernstein, former chief economist to Vice President Joe Biden, stated in 2015 that "[f]aster productivity growth would be great [but] I'm just not at all sure we can count on it to lift middle class incomes." This theory rests on the observation that while average pay and productivity have risen, median pay hasn't increased by nearly as much. This is a sign that the typical worker does not share equally in the gains from economic growth, and thus the argument is fundamentally about inequality of labor income.

But this line of argument could mask more complicated questions about inequality of productivity. For example, if median pay is diverging from average pay and productivity, is it because elites are restraining growth in the median wage relative to median productivity, or is it because the median worker is not increasing his productivity as rapidly as the average worker is? Given that we cannot measure the median worker's productivity directly, the key issue for this debate is whether we can infer that something has gone awry with the productivity-to-pay transmission mechanism by looking at trends in pay alone. This point requires further investigation.

In the case of the first assertion, the argument and chart that Hillary Clinton deployed in 2015 offer a useful test. The data Clinton cited show that, between 1948 and 1973, worker productivity and pay increased by 96% and 91%, respectively. However, between 1973 and 2017, productivity grew by 77% while pay grew by a paltry 12%. Specifically, that chart contrasted the cumulative growth in the total economy's net productivity (that is, output per hour net of depreciation) with growth in average hourly compensation for production and non-supervisory workers using two separate adjustments for inflation. If one assumed that these data sources allowed for an apples-to-apples comparison of an average worker's productivity and his corresponding pay, the post-1973 decoupling would indeed be troubling.

This comparison, however, suffers from serious methodological flaws that render it useless at best and downright misleading at worst. To briefly summarize: it doesn't use compensation data for the same workers that are reflected in the productivity series; it uses a consumer price index that overstates inflation (thereby understating real income growth); it uses a consumer price index for wages instead of an output price index (which would be more appropriate because the question at hand is whether people are paid for what they produce, not whether they are paid for what they consume); and it includes the output of the self-employed in productivity but excludes their compensation from the pay series. Adjusting for these factors, as a number of the above-cited authors show, reveals that real average hourly compensation in the non-farm business sector actually grew 81% from 1973 to 2017, just a touch below productivity, which grew 83%. In fact, the two series increase in lockstep all the way back to 1948, growing 237% and 234%, respectively, over the whole time period. On average, at least, the market still connects ability to earn with ability to produce.

The second assertion, that rising productivity no longer benefits the middle class, is well exemplified by the evidence that hourly compensation for the median worker has grown by about 30% since 1973 while the average worker's pay increased at roughly twice that pace (when comparing similar data sources and using a consumer price index). According to Josh Bivens and Larry Mishel of the progressive Economic Policy Institute, the reason for the difference in fortunes, which they assert is a result of a breakdown in the relationship between productivity and pay, is that "typical workers' bargaining power has been intentionally hamstrung by a portfolio of intentional policy decisions on behalf of those with the most income, wealth, and power." They specifically refer to tight monetary policy, the decline of unionization, and a low minimum wage. It seems implausible, however, that lawmakers could implement policies that would yield a tight relationship between pay and productivity for the economy as a whole but not at all for the middle class. Instead, there is a much simpler explanation available: that the median worker's productivity is growing more slowly than the average worker's productivity.

As Stanford's Edward Lazear argues, "changes in trade and technology have raised the productivity of highly trained, highly educated workers relative to the less skilled." For example, as global integration opens up new markets, which begets larger firms, it elevates the scale of operations and thereby increases the returns to management. But as managers tend to be relatively more educated and well compensated, these changes only further boost their advantages. Or in the case of technology, increased adoption of sophisticated productivity-enhancing technology often requires highly skilled or highly educated workers. The gains from technological innovation may therefore disproportionately redound to the benefit of those most suited to use it. But in the case of many service-sector jobs or positions that do not require as much education or training (say, in the case of a cashier, a trucker, or a barber), there isn't as much scope for either globalization or technology to raise productivity as rapidly.

Besides changes in technology and globalization that may have disproportionately benefited higher-skill workers, the potential divergence between median and average productivity could be further exacerbated by the changing nature of competition, firm size, and the sorting of workers. New research finds a tight link between the wages that workers receive and the types of firms that they work for, which are increasingly characterized by differing degrees of productivity and profitability. There is at least suggestive evidence in this literature that inequality of productivity is rising and that this could be driving inequality of incomes.

First, as MIT's John Van Reenen argues, globalization and technology (such as the internet, which facilitates price and product comparisons and increases choice) have enabled consumers to be more sensitive to price and quality. These changes in consumer behavior have given rise to a "winner take most" style of competition, whereby slight advantages in price or quality can lead to large changes in market share for businesses. As a result of this phenomenon, David Autor (also of MIT) and co-authors find rising firm concentration, particularly since the mid-1990s, in which industries have become increasingly dominated by a handful of large "superstars," high-productivity and high-profit firms. The study finds that the industries that have seen the largest increases in concentration are also the most innovative (measured by patenting intensity) and productive. This suggests that rising concentration results from more intense competition and superior productivity among the top firms, rather than anti-competitive practices.

At the same time, researchers are also finding a rising dispersion of productivity among firms both in the United States and abroad. For example, in a 2016 paper studying firms in developed countries, Dan Andrews and his colleagues find that the top 5% of firms, labeled "frontier firms," lead the pack with rapid rates of productivity growth while the "laggard firms" demonstrate slow productivity growth. If workers' fortunes are in turn associated with the nature of their firms, then rising dispersion of productivity among firms could manifest itself in dispersion of productivity among individuals as well.

A team of researchers with access to a dataset covering the great bulk of employer-employee matches in the United States finds that almost the entire rise in labor inequality (below the 99th percentile of the wage distribution) since the 1980s can be linked to the changing wage profile of firms. Specifically, the researchers argue that "workers' earnings in almost all percentiles have evolved in line with those of their coworkers during this 30+ year period." The authors explain that this phenomenon is fueled by rising returns to skill and skills-based worker sorting and segregation across firms. In other words, not only are highly paid workers increasingly likely to be found at high-wage firms, but those same firms are now less likely to employ low-wage workers.

One good example of this, highlighted by Van Reenen, is the difference between McKinsey and McDonald's. Not only are more highly educated professionals gravitating toward the consulting powerhouse, the company may be less likely to offer employment to less well-educated workers (and vice versa in the case of McDonald's franchises). The authors also note that the rise in inequality has virtually nothing to do with a rising dispersion of firm pay premiums.

Putting this all together, if certain firms are getting larger to deal with a hypercompetitive global landscape, those firms are among the most innovative and productive in their industry, and high-skilled workers increasingly sort to them while lower-skilled workers are increasingly shunted away from them, then it seems quite possible that rising differences between firms are also contributing to increased inequality of productivity, which is then manifested in increased inequality of pay. In this scenario, the increase in income inequality would be consistent with a tight linkage between pay and productivity and would coincide with increased competition, innovation, and productivity growth.

This evidence is by no means conclusive, but it does suggest that the factors driving labor-market inequality may be functions of these changes in the nature of our economy, as opposed to being the product of a "rigged" system. Of course, the rules that govern markets matter, and the priorities of policymakers do too. Evidence like this doesn't mean that we should be satisfied with the status quo. There is a lot of room to improve the fortunes of lower- and middle-income workers. But it is important to spend less time on the question of whether companies aren't paying workers fairly relative to their productivity, and refocus the debate on questions like how we make workers more productive in their existing jobs and how we create more high-productivity jobs that are accessible to all.

Unfortunately, progressive politicians aren't the only ones failing to ask and answer these questions. Conservatives increasingly insist the economy is rigged as well.

BAD CAPITALISTS

Especially since the election of Donald Trump, which threw the traditional Republican coalitional balance out of alignment, Republicans have been feuding among themselves in order to settle upon a revised ideological framework that holds the coalition together. Of particular importance to this debate is how policy should address changes in the nature of work and the degree to which elites can be blamed for the woes of the working class. And the intra-conservative debate about these questions has seen the rise of a populist camp with a distinctly declinist set of premises.

The populists' case rests on the diagnosis that economic conditions have deteriorated for a large swath of the country, particularly non-college-educated men, which has given rise to a slew of poor social outcomes, such as the dissolution of the family, "deaths of despair," and geographically concentrated worklessness. A solid causal link between changing economic conditions and these other negative social outcomes is an essential component of this narrative. And accusations about the dark motives of assorted market and political actors have been crucial too.

Generally, the argument is that misguided policymakers, obsessed with abstractions like GDP, have allowed markets to run amok, which decimated the working class and propped up the wealthy and our foreign rivals. This diagnosis leads its advocates to the conclusion that markets are merely a "tool, like a staple gun or a toaster," in Tucker Carlson's phrasing, though the politicians and capitalists who benefit from the status quo pretend it is an end in itself.

Oren Cass, formerly director of domestic policy for Mitt Romney's 2012 presidential campaign and author of an important book called The Once and Future Worker, makes a form of this argument. Cass argues that the plight of the working class is largely due to grossly negligent policymakers who have treated them with a sort of "benign neglect." The neglect is a byproduct of a misguided framework he calls "economic piety." In this telling, policymakers blindly hope that a growing economic pie will benefit all, either directly in their pocketbooks or indirectly by financing redistribution. Although Cass doesn't go quite as far as Carlson in his characterization of working-class malaise, the stagnation or outright decline in economic conditions he speaks of is nonetheless said to be caused by negligent elites.

Carlson, Cass, and others who make forms of this argument certainly do raise important points about the tradeoffs between equity and efficiency, but the narrative of elite-engineered or -enabled decline is ultimately a red herring.

To start, both Carlson and Cass paint an inaccurately bleak picture of the fortunes of working-class Americans over time. Carlson's key contention is that over the past few decades "male wages declined," which "cause[d] a drop in marriage, a spike in out-of-wedlock births, and all the familiar disasters that inevitably follow — more drug and alcohol abuse, higher incarceration rates, fewer families formed in the next generation." Likewise, Cass claims that "[t]he problem is not one of unequally shared gains. A significant share of the population, perhaps even a majority, has seen no gains at all and may now be going backward." On the latter point, Cass argues that the incomes of young or non-college-educated men are creeping ever closer toward the poverty line associated with a family of four, which implies an absolute decline of incomes. In addition, he says that "American workers are in crisis," citing evidence that "millions have fled the labor force entirely — the 19 percent of prime-age males lacking full-time work in 2018 would have marked the worst year on record prior to the Great Recession."

Both Cass and Carlson argue that a major reason for the decline or stagnation in male pay and the retreat from work is the decline of manufacturing, and more broadly a widespread reduction in the domestic labor demand of businesses. But an extended debate between Winship and Cass on the website of National Review revealed that the economic declensionist case isn't nearly as strong as its champions have claimed. For example, between 1973 and 2018, hourly wages have grown anywhere between 7% and 13% for any given decile of the bottom 50% of male earners. Of course, that includes periods of stagnation for men, mainly during the 1970s and 1980s as women joined the labor force in large numbers (thereby boosting the overall labor supply and restraining male wage growth in relative terms). And to be sure, these gains for working-class men aren't impressive and aren't nearly as large as the gains further up the income scale. But even an unimpressive increase is not a decline. And with no decline, it is much more difficult to make a causal argument about changing living standards driving changes in social patterns.

As for rising male worklessness, it is indeed true that male labor-force participation is near all-time lows, but it has also been on a steady decline ever since the early 1950s — long before the collapse of manufacturing employment or the supposed embrace of "economic piety." In fact, prime-age male labor-force participation today sits exactly at what the 1950 to 2000 linear trend would predict. In other words, this is a long-running secular trend and not some new phenomenon. More important, as Winship has noted, "three quarters of the decline in prime-age male labor-force participation has involved men who say they do not want a job." This, coupled with the fact that wages are higher, suggests that the predominant factor behind the reduction in the fraction of prime-aged men working is that the willingness to supply labor has declined — not that employers have reduced their overall demand for male workers (which would be more consistent with declining wages). This reduction in the supply of labor could have arisen from both benign sources (such as changes in female employment and child-rearing responsibilities) and harmful sources (such as the increase in disability claims and the extent to which the safety net may discourage work).

So, to bridge the divide between Winship and Cass, it seems reasonable to conclude that while the reduction in male labor supply (rather than a reduction in business labor demand) may be the key culprit in the decline in labor-force participation, a shift in the composition of business demand for male labor has altered the array of work options unfavorably, in relative terms, for less-educated men. This change in the composition of labor demand along the lines of education and skill and a reduced supply of labor is consistent with long-running labor-market trends, rising wages, and rising inequality.

In practical terms, this shift in the composition of labor demand means that the bottom of the occupational or wage distribution has, over time, been increasingly comprised of non-college-educated and male workers. For example, when studying the bifurcation of the labor market across the college and non-college divide, MIT's David Autor finds that, since the 1980s, the reduction in middle-skill employment among college-educated workers was offset by equivalent gains in high- and low-skill work, whereas for non-college-educated workers, the much larger reduction in middle-skill employment was overwhelmingly marked by a shift to lower-skill employment. These changes in relative positions in the labor market are nonetheless consistent with rising wages for all income groups over time and are not reflective of some widespread polarizing of the labor market in absolute terms.

The upshot of all this is that non-college-educated workers (who increasingly constitute a shrinking portion of the workforce given rising educational attainment) have been essentially shunted into relatively low-wage, low-productivity work by technological change and globalization. Autor explains that these occupational changes are characterized by a shift in the composition of labor demand away from manufacturing, clerical, and administrative work toward custodial work, food services, protective services, recreation, health services, transportation services, and laborer occupations. Although these jobs yield higher living standards in absolute terms than they did decades ago (as the wage data suggests), they don't necessarily afford the same relative position in society. This may carry its own set of complications. Crucially though, this shift in the composition of labor demand cannot really be attributed to policymaker negligence or some elite-engineered plot. In the case of technology, for example, the advent of office computing software effectively obviated the need for prior levels of mid-skill secretarial and clerical employment.

As for the decline of mid-skill manufacturing employment, of course some portion is due to a conscious decision to pursue more open trade, and also to unfair Chinese trade practices (such as intellectual-property theft and competition from subsidized state-owned enterprises) that policymakers did not effectively combat. Typical estimates of manufacturing job loss find that China shock explains about 15% to 20% of the overall decline, with an upper bound of about 30%. But much of the loss of manufacturing employment is the result of shifts in the product cycle and the fact that as countries get richer, they shift away from manufacturing.

University of California, Davis, economist Katherine Eriksson and co-authors define the product cycle as the process by which, in both a domestic and cross-country context, "industries spawning in high-wage areas with larger pools of educated workers [eventually move] to lower-wage areas with less education as they age or become 'standardized.'" By tracing the evolution of the manufacturing sector (by product and location) within the United States back to 1910, the researchers found that the areas that were hardest hit by competition with China were also the ones that were the most "late stage" in the production cycle, and therefore prone to competition and already in the process of phasing out.

Putting all of this together, structural and long-running global forces have resulted in an economic landscape in which non-college-educated workers who used to occupy decently productive and well-paying medium-skill jobs no longer have the same degree of access to either these jobs or an alternative that affords them the same relative earnings position in society. However, this does not necessarily imply an overall decline in pay over time, nor a decoupling between what a worker produces and what he earns. Instead it suggests that there's an increased prevalence of relatively low-productivity jobs that do not yield pay gains as rapidly over time as higher-productivity jobs. This is consistent with the economy's decades-long shift from goods production to service provision — the latter of which is not as conducive to rapid productivity gains because it isn't capital intensive.

Of course, we are not resigned to this fate, nor should we accept it. Even if male pay hasn't declined, and even if changes in the nature of work available to non-college-educated men are largely explained by long-running economic forces operating around the world rather than some elite-driven conspiracy, it still leaves us with lots of room to pursue policies that could increase wages and access to high-quality jobs for all lower- and middle-income workers.

Moreover, nothing in the preceding discussion disputes the existence of troubling social trends such as a reduction in marriage, declining social capital, and increased rates of suicide and drug use. What is driving these changes remains an open question, and surely these trends should be on the minds of policymakers as they attempt to restore faith in our economic and political system.

But it matters whether we see these forces as products of an elite assault on the ways of life of working-class Americans (or even of elite contempt or neglect), or whether we understand them as economic changes that require a response that no one in our politics has been nimble enough to mount. At the heart of today's populist arguments lies the premise that if our leaders actually cared about ordinary Americans, then they surely would have managed such a response by now — or could fix it all now if they tried. But is that right?

BETTER JOBS AND HIGHER WAGES

Richard Reeves, a scholar at the Brookings Institution, frames the question well: "People want a job with a decent wage — why is that so hard?" Part of the reason it is so hard is because powerful global economic forces are changing the nature of work and the relative rewards of different skillsets.

The most significant among these shifts are the opening of new markets (which brings both fiercer competition and greater returns to scale), the evolution of the product cycle, a decades-long shift from goods production to service provision and the associated drop-off in capital investment, new technologies that are disrupting established occupations and increasing the returns to skill, the rise of a "winner take most" style of competition and superstar firms, increased skills-based sorting, rising dispersion in productivity between firms, and the slowing diffusion of innovation. These are problems without straightforward solutions. And it is especially hard to know how to address them without giving up the benefits of present and future growth and prosperity.

Nonetheless, an economic agenda that works in this modern context must be both inclusive and pro-growth. It should be inclusive not because inequality causes anything bad per se (inequality is a symptom of both good and bad forces), but because a system in which a rising tide doesn't eventually lift all boats is undesirable. Likewise, the economic agenda should also be pro-growth because it is much easier to foster more equally shared gains in a faster-growing economy than in a slow-growing economy. In other words, faster growth is likely a precondition for more equal growth.

An inclusive, pro-growth agenda would probably need to include pro-investment tax reforms, policies to boost innovation and its diffusion throughout the economy, changes in the government's role in job training, significant expansions in apprenticeships and pathways for students who do not wish to go to college, greater supports to encourage work and make it easier for families to raise children, and a monetary-policy framework that is conducive to tight labor markets. Some of these kinds of policies are advocated by some of today's populists. Oren Cass, for instance, proposes a number of them in his recent book. But it makes an enormous difference whether they are proposed as ways for our political and economic system to try to respond to changing circumstances or as remedies for intentional elite sabotage of the lives of working-class Americans. To begin by accusing political and economic decision-makers of bad faith is both unfair and counterproductive — and it makes those elites less likely to sign on to any proposed reforms. If we instead see that these are problems that essentially everyone wants to solve, we will be more likely to find our way to politically plausible remedies.

Given that businesses pay people for what they produce, the core of any path to increased wages is to boost worker productivity. For example, President Obama's Council of Economic Advisers found that if productivity had grown more rapidly from 1973 to 2013 (that is, if it had grown at the pace prevailing in the previous 25 years), "incomes would have been 58 percent higher...[and] if these gains were distributed proportionately in 2013, then the median household would have had an additional $30,000 in income." The goal isn't to raise overall productivity by encouraging greater output from higher-income workers exclusively, but instead to make lower- and middle-income workers both more productive within their existing jobs and more able to transition into higher-productivity jobs. The data suggest that there is ample room for improvement.

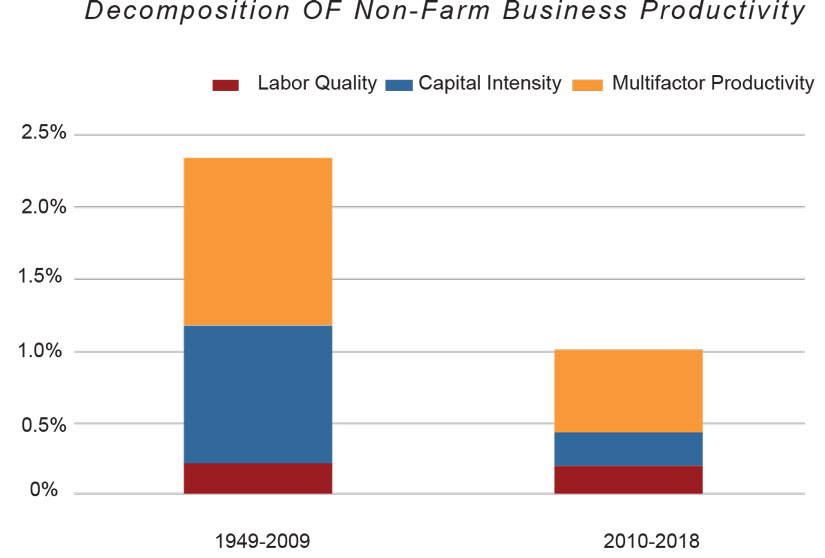

Productivity growth has slowed dramatically in recent years. From 1949 to 2009, productivity in the non-farm business sector grew annually by 2.4% on average. But since 2009, it has grown just 1% on average. When breaking productivity growth apart into its three subcomponents (labor quality, capital intensity, and multifactor productivity), it is clear that there are two main sources of the slowdown. As the chart below demonstrates, of the 1.4 percentage-point decline in productivity growth, 0.8 percentage points are due to reduced capital intensity (less investment per worker), and the remaining 0.6 percentage points are due to reduced multifactor productivity (that is, the efficiency of production using both labor and capital inputs, often thought of as a catch-all for technology and innovation).

Given the extraordinary decline in capital intensity relative to historical norms (0.2% during this decade versus 1% historically), a key component of any economic agenda will be increased supports for capital investment by businesses. Perhaps the best way government policy can encourage productive investments is through tax reform. The ideal solution would involve transitioning the existing corporate income tax into a destination-based cash-flow tax (or DBCFT). The DBCFT has two main advantages relative to a corporate income tax with respect to investment. First, all capital expenditures would be immediately written off rather than depreciated over time as they are under an income tax. This change would place a 0% effective marginal tax rate on new investment, thereby rendering the business tax system neutral toward investments earning normal returns. Second, the destination-based feature of the tax would eliminate all tax incentives for locating investment or profits abroad by shifting the tax base away from domestic production to domestic consumption.

In order to further boost productivity growth, policymakers should take up a comprehensive pro-innovation agenda. Given rising dispersion of productivity among "frontier" and "laggard" firms, evidence suggesting that innovations aren't diffusing as rapidly throughout the value chain as they used to, and the fact that research productivity has diminished and therefore each incremental unit of innovation has become more expensive, it will be important for policymakers to boost the overall federal commitment to subsidizing research and development. In addition, policymakers should work to ensure that there aren't any unnecessary impediments that prevent innovations from cascading throughout the value chain.

Policymakers should also look for ways to make businesses and workers better able to withstand economic shocks, such as increased competition from abroad. Such an agenda would need to significantly overhaul the federal government's approach to job training. According to a recent study by the Council of Economic Advisers, there are 47 different job-training programs serving over 10 million people at a cost of $18.9 billion per year. Unfortunately, what little evidence exists to evaluate these programs suggests they are largely ineffective. In The Once and Future Worker, Cass proposes an interesting conceptual starting point for discussion that involves shifting the government's role away from administering training programs toward financing an employer-led system of job training.

Relatedly, creating a diverse array of pathways into the middle class should also involve a major rethinking of our "college or bust" approach to education. As Cass argues effectively, despite the fact that fewer than one-in-five students will complete high school on time, get a college degree, and then find a job in a field related to their studies, the entire educational system is oriented toward helping the students who are already most likely to succeed in the modern economy. A better way forward would obviously involve improving our high-school education system, but would also include significant expansions of apprenticeship programs and a career-oriented educational path for students who do not wish to attend college.

Policymakers should also consider ways to reorient the tax code toward encouraging work and making it easier for families to support their children. Given evidence of a decline in the willingness of male workers to supply labor, and given research demonstrating the beneficial intergenerational effects of raising children in a married household, policymakers should rethink the existing patchwork of deductions and credits in the tax code and reorient them to encourage work and marriage and to defray the costs of raising children — even if it means expanding the total federal commitment to these purposes.

Lastly, not only would all of these policies be even more effective if the conduct of monetary policy were more conducive to tighter labor markets, but lower-income workers, whose wages and job fortunes are much more tied to the business cycle than other workers, would stand to benefit disproportionately. While the goals of monetary policy are to achieve maximum employment and stable prices, the Fed's past approach has put too much stock in the theory of a robust inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment. This way of thinking, most evident in the recovery from the Great Recession, has at times led the Fed to adopt tighter monetary policy than is appropriate and thus has resulted in higher unemployment and several unnecessarily lost years of wage growth for low-income workers.

FACING REALITY

It is not a coincidence that some elements of this policy agenda are not so different from those on the agenda of the populist conservatives who offer concrete policy ideas. The problem with their approach to America's challenges is not in their prescriptions but in their diagnoses. They insist that our problem is leaders who hold the public in contempt. This encourages an attitude of reciprocal contempt and the attribution of dark motives, all of which encourages the wrong approach to our political economy.

The fact is that our country has been subject to some complicated, largely unexpected, and very hard-to-handle economic pressures in the last several decades. It is not shocking that our political leaders have not always responded well to them. But by insisting that these forces have done far more economic damage than they really have, that it would have been easy to address them, and that the only reason they were not effectively dealt with was that willful neglect served the interest of elites, today's populists encourage maximal cynicism in the public. This will only make it harder for future leaders to acknowledge the complexity of the challenges we face and to take steps toward addressing them.

Such scapegoating is politically expedient and intuitive, but it is rooted in bad economics and will only lead to an even darker politics. A better understanding of the structural economic forces shaping the labor market over recent decades will allow for an agenda that is more likely to raise wages, create better jobs, and ultimately lead to greater prosperity for working-class Americans. Getting it right won't be easy, and pretending it ought to be easy will only make it harder still.