Economic Liberty in the Courts

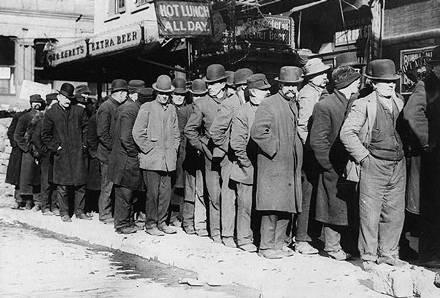

Over the past two years, government intrusions into the private economy have been eye-opening and unprecedented. First came the deluge of taxpayer dollars to bail out troubled banks. Then the federal government began dictating executive compensation and bonuses at large financial firms. America's largest automakers were effectively nationalized, and lawmakers tried to up-end standing agreements between mortgage lenders and home owners. Most recently, much of America's health-care industry — nearly one-sixth of the economy — fell under federal control. Washington will soon intrude into the most basic economic decisions — what to buy with one's own money — by forcing all Americans to purchase the health insurance that federal lawmakers think they should have.

Faced with chaos in the markets and the specter of economic disaster, both the Bush and Obama administrations justified some of these aggressive measures as emergency responses meant to avert depression and speed economic recovery. But the lessons of American history suggest that, attempts to rationalize them notwithstanding, many of these controversial policy innovations will sooner or later end up in court — and quite possibly the Supreme Court, tested against some standard of constitutionality. The question of economic rights, and economic liberty, will therefore soon take center stage in American jurisprudence.

But the place of economic liberty in our constitutional tradition is far from clear, and its story far from simple. The centerpiece of that complicated story is the 14th Amendment, and our changing understanding of it. This is, in particular, a tale of how New Deal-era jurisprudence broke from the amendment's original meaning — and left behind a trail of precedents that today distorts the views even of self-described originalists.

ECONOMIC RIGHTS AND THE 14TH AMENDMENT

Among contemporary jurists, conventional wisdom holds that economic rights as such have no legitimate place in our constitutional tradition. While certain important civil rights (especially those understood to be political rights, like voting, free speech, or the freedom of the press) are taken to merit special scrutiny and protection, economic rights (like the right to contract freely, or to reap the benefits of one's labor) have second-class status.

Even judges committed to interpreting the Constitution in accordance with its original meaning often deny that the framers of the document, and of its amendments, intended to protect economic liberty. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, for instance, has argued that the Court ought not "provide a constitutionalized protection" for economic rights, and has commended "Supreme Court decisions rejecting substantive due process in the economic field." And Judge Robert Bork has dismissed economic liberty as an outgrowth of "natural law" — a concept spawned from the imaginations of laissez-faire judges, and nowhere to be found in the Constitution.

In making the case for the subordinate status of economic rights, originalists tend to find their inspiration not in historical examples of the framers' intent, but rather in arguments about the potential consequences of constitutional protections for economic rights. If judges treated economic rights as they do other civil rights, Scalia warned in a 1984 lecture, "we [might] find ourselves burdened with judicially prescribed economic liberties that are worse than the pre-existing economic bondage." Such judicial reasoning, he argued, could (for instance) end up in a "constitutionally prescribed" right to some set minimum wage.

Surely Scalia's concern is not without merit. But by letting fears about the practical consequences of economic rights trump what the Constitution actually says on the subject, the originalists' approach goes too far. For even if it secures us against the possible unwelcome results of protecting economic rights, it also precludes the welcome and constructive ones. More important, in overlooking the Constitution's original meaning, this approach denies Americans some of the very liberties the document was intended to secure.

What, then, does the Constitution actually have to say on the subject of economic rights? Scholars and jurists of all dispositions agree that much of the answer lies in the 14th Amendment, and in particular its first (and most important) section. Indeed, no portion of the Constitution has been more thoroughly debated and dissected than the following 80 words:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Heated disputes over the meaning of this section began almost as soon as the amendment was ratified; much of the contention has turned on just what the "privileges or immunities" of American citizenship are, and what is included within the sweep of "liberty." Today we are accustomed to such arguments in the context of public debates over civil rights. Less familiar, however, is the central role that economic rights and liberties played in the definition — and the original application — of the concepts and terms at the heart of the 14th Amendment.

A proper understanding of the 14th Amendment, and of its relationship to economic rights and liberties, is impossible without considering its historical context — especially concerns about Americans' ability to earn a living and take part in commercial activity. In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Southern states had attempted to maintain the functional inequality of newly freed slaves by subjecting them to unequal laws. While whites could operate unfettered within the economic sphere, blacks were limited in their choices of occupation, in their freedom to own and acquire property, and in their right to engage in lawful contracts. The aim of the 14th Amendment, then, was to force the states to protect all citizens' civil liberties equally — liberties that, in many cases, pertained to economic activity.

This emphasis on economic rights was also apparent in the debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which immediately preceded passage of the 14th Amendment and was closely intertwined with it. The act's first section spoke of "citizens, of every race and color," who "shall have the same right, in every State and Territory in the United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, enjoyed by white citizens." Within this context, the rights deemed most important were those of contract and property — in part because these were the very liberties that the "Black Codes," passed in the wake of the 13th Amendment, had intended to prevent blacks from exercising.

The congressional debates over the Civil Rights Act make clear that these economic rights were also seen as fundamental human liberties. Illinois senator Lyman Trumbull, the leading champion of the legislation in the Senate, explained that the "first section of the bill defines what I understand to be civil rights: the right to make and enforce contracts, to sue and be sued, and to give evidence, to inherit, purchase, sell, lease, hold, and convey real and personal property." Similar sentiments were expressed by supporters of both the Civil Rights Act and the 14th Amendment in both houses of Congress. As a member of the House from Ohio argued, "It is idle to say that a citizen shall have the right to life, yet to deny him the right to labor, whereby alone he can live. It is a mockery to say that a citizen may have a right to live, and yet deny him the right to make a contract to secure the privilege and reward of labor." Another member argued that the object of the Civil Rights Act was "to secure to a poor, weak class of laborers the right to make contracts for their labor, the power to enforce the payment of their wages, and the means of holding and enjoying the proceeds of their toil." He went on to ask: "Do you call that man free who cannot choose his own employer, or name the wages for which he will work?" In the late 1860s — in the environment out of which the 14th Amendment emerged — civil rights were seen as rights to equal opportunity and equal treatment by the law, especially in the economic sphere.

Of course, the 1866 Civil Rights Act was not without its critics. They insisted that the legislation reached beyond congressional authority and intruded into the realm of state powers, especially in states where, as one representative from Indiana said, any "negro or mulatto" was forbidden to "come into the State and purchase and hold real personal property." Persuaded by the states'-rights argument, President Andrew Johnson issued a veto; the Congress, however, voted by an overwhelming majority to override it. Defending the act, one senator argued that without these rights the newly freed slave could be deprived of "the fruits of his toil and his industry"; he would therefore be reduced to a condition no better than the slavery from which he had just escaped.

Nevertheless, some among both the act's supporters and opponents insisted that the changes it sought to implement would require a constitutional amendment (to overcome opposition in the states and to secure the rights it enshrined against future challenges). Such an amendment was necessary, as future president James A. Garfield (then a member of Congress) put it, "to lift that great and good law above the reach of political strife, beyond the reach of the plots and machinations of any party, and fix it in the serene sky, in the eternal firmament of the Constitution, where no storm of passion can shake it and no cloud can obscure it."

The 14th Amendment was clearly intended to provide constitutional protection to the rights enumerated in the 1866 Civil Rights Act, and so to protect the bill from being repealed by an ordinary act of legislation. Yet it is too simplistic to say that the 14th Amendment merely "constitutionalized" the Civil Rights Act; it obviously did much more. Chief among its aims was the abolishment of "all class legislation in the States," as one of its congressional champions put it, in order to enforce "the principles lying at the very foundation of all republican government": the principles of equality, protection of property, and the impartial rule of law.

This understanding of what lies at the heart of republican government — and especially the central role of property rights — is well grounded in the American constitutional tradition. James Madison asserted that the purpose of the state was to protect property — "this being the end of government, that alone is a just government, which impartially secures to every man, whatever is his own."

Abraham Lincoln, in his critique of slavery, similarly insisted on the importance of impartial laws meant to protect citizens' property. In 1858, during one of his celebrated debates with rival Stephen Douglas, Lincoln argued that slavery denied the inherent rights of blacks by seizing the bread they had earned by their own labor: "But in the right to eat the bread, without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, [the black man] is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man." Thus, Lincoln contended, "When the white man governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government — that is despotism."

Beyond asserting the equal economic rights of blacks and whites, Lincoln even went so far as to reject distinctions within the economic sphere based on class. "There is no permanent class of hired laborers amongst us," he said in 1859. "Twenty-five years ago, I was a hired laborer. The hired laborer of yesterday, labors on his own account today; and will hire others to labor for him tomorrow. Advancement — improvement in condition — is the order of things in a society of equals." To Lincoln's understanding, the right to equal treatment in the economic sphere was essential to the possibility of social advancement in America.

Lincoln's views on free labor informed the 14th Amendment, which placed the principles of liberty, equality, and rights detailed in the Declaration of Independence at the root of our constitutional order. His thinking also influenced the Supreme Court, which elaborated on these notions in the latter half of the 19th century and into the early part of the 20th century.

One particularly noteworthy example of the Court's efforts to articulate the underlying logic of the 14th Amendment is the 1886 case Yick Wo v. Hopkins. At issue was a seemingly benign San Francisco city ordinance that allowed laundries housed in brick or stone buildings to operate without restrictions, while requiring that laundries operating out of wood buildings be licensed (in order to reduce the potential for fires). Just a year before, the Court had upheld the regulation of business hours in laundries as a legitimate health and safety measure, also out of concern for fire hazard. But the San Francisco statute seemed to have been inspired by other motives: It turned out that the laundry licensing board, with no explanation, granted permits to laundries operating in wood structures when the applicants were white, but denied them when the applicants were Chinese. Under the guise of public-safety regulations, the city was in fact using the ordinance to discriminate against laundries owned and operated by Chinese immigrants in a wholly arbitrary manner.

The Court ruled unanimously in Yick Wo's favor, holding: "When we consider the nature and the theory of our institutions of government, the principles upon which they are supposed to rest, and review the history of their development, we are constrained to conclude that they do not mean to leave room for the play and action of purely personal and arbitrary power." Here, a putative regulation of public safety had been implemented for no other practical reason than "hostility" to "the race and nationality" of the petitioners, rendering it an arbitrary and unjustified regulation in "the eyes of the law."

It was, in other words, the very sort of partial legislation the 14th Amendment was meant to overcome. The Court moved to protect the equal rights of Americans to pursue prosperity: to operate a business free from government restrictions that applied unequally and unfairly, based on race or class. At issue was a question of economic liberty, which both the 14th Amendment and the decades of Supreme Court jurisprudence that followed it had treated as essential to civil liberty and civil rights.

But this understanding of the right to engage in economic activity was not to endure. It would be changed dramatically in the wake of the New Deal, as the Supreme Court responded to major federal interventions in the private economy by reading economic liberty out of the Constitution.

OBSCURING LIBERTY

The New Deal critique of the "Old Court" and its "nine old men" has become the stuff of legend in the legal world. According to this now-familiar narrative, the Court had, by the time of Franklin Roosevelt's election, come to be dominated by an extreme laissez-faire ideology that denied the government any role in regulating economic activity — leaving the country at the mercy of businessmen and powerful corporations.

This tension between the "old" and "new" approaches to economic regulation came to a head as the Court struck down the first wave of New Deal legislation. Even though the Court was often unanimous in its opinions, and included credentialed liberals like Justices Louis Brandeis and Benjamin Cardozo, its restrictions of Congress's power under the commerce clause — prohibiting the national government from setting prices or regulating local activity — prompted President Roosevelt to insist that, with the Court's opinions, "we have been relegated to the horse-and-buggy definition of interstate commerce." F.D.R.'s early efforts to pressure the Court (which climaxed in the crisis over his failed attempt to increase the number of justices) did not succeed. But in time — and through his insistence that any new justices take a more expansive view of federal power — Roosevelt brought about a dramatic change in the jurisprudence of economic liberty.

In the past decade, scholars have offered a far more rounded picture of the "Old Court." They note that it upheld the vast majority of government regulations that came before it, and that it reached its decisions in a principled, constitutional manner. And yet we continue to be influenced by the New Deal telling of history — which informs us that, through the "Constitutional Revolution of 1937," the Court solidified expansive national power while simultaneously protecting "civil liberties" that no longer included economic rights.

Thus, in the aftermath of the New Deal, the Court took longstanding constitutional rights — rights to labor and economic activity — and simply wiped them out of memory. Forms of liberty that had been respected even before the adoption of the 14th Amendment, and that had been given clear constitutional protection by that amendment, were suddenly declared not to be rights at all. Not only were economic liberties denied judicial protection, but Congress's commerce-clause power was taken to have virtually no limits.

As an example, consider the case of Roscoe Filburn. Filburn was an Ohio farmer who sowed and harvested more wheat than was allowed under the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938. But Filburn did not sell his "excess" wheat: He used it to feed his own animals. He therefore argued that his practices had no bearing on interstate commerce, and so were not covered by the law. His case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which held in 1942 that, even though his wheat never traveled beyond his own farm, Filburn's home consumption was subject to regulation — because it could, however indirectly, affect the overall price of wheat on the open market.

In dismantling limits on Congress's power under the commerce clause, the Court would also cease protecting economic liberty. Justice Felix Frankfurter (a Roosevelt appointee) put the matter bluntly in his concurring opinion in the 1949 free-speech case Kovacs v. Cooper: "In considering what interests are so fundamental as to be enshrined in the Due Process Clause," he wrote, "those liberties of the individual which history has attested as the indispensable conditions of an open as against a closed society come to this Court with a momentum for respect lacking when appeal is made to liberties which derive merely from shifting economic arrangements."

As learned as Frankfurter was, the former Harvard law professor was closed to the fact that economic liberty was, from the perspective of those who framed the 14th Amendment, one of those indispensable conditions of an open society. Such liberty could not be reduced to or altered by "shifting economic arrangements" precisely because it was part of the foundation of a free society — not, as the New Dealers held, a mere outgrowth of it.

Despite the fact that economic liberty was frequently referred to as "personal liberty" from before the founding until long after the framing of the 14th Amendment — and viewed as a freedom on par with, say, the freedom of speech — New Deal jurisprudence suddenly insisted that "personal" liberties were distinct from (and indeed preferred to) "economic" liberty. President Roosevelt himself embraced this understanding in his famous 1932 Commonwealth Club address, insisting that the people had "two sets of rights." In one set Roosevelt placed the rights of "personal competency," by which he meant freedom of thought and "personal" living; into another, he placed rights "involved in acquiring and possessing property." The latter category, Roosevelt suggested, could not exist without the government, which therefore had the authority to "intervene" to adapt "existing economic organizations to the service of the people" based on "enlightened administration."

But perhaps the most articulate defense of the new thinking on economic liberty came from Justice Harlan Stone (whom Roosevelt would eventually elevate to chief justice in 1941). Stone's views were expressed in his now-famous footnote to the Court's opinion in a 1938 case, United States v. Carolene Products.

Carolene Products was a company that manufactured "filled milk," a combination of skim milk and vegetable oil. It was a perfectly safe and healthy product that offered advantages over whole milk — particularly for less well-off consumers — as it was substantially cheaper and more readily storable. Filled-milk producers were therefore viewed by whole-milk producers as dangerous competitors. And in 1923, a coalition of dairy farmers lobbied Congress to pass the Filled Milk Act, which — citing legislative "findings" that filled milk was unhealthy and might be mistaken for whole milk by consumers — prohibited the movement of the product across state lines. Under the guise of protecting consumers from fraud and harm, Congress thus enacted legislation that sought to damage a perfectly legitimate business for the benefit of a competitor.

The act was a classic instance of "class legislation," in which Congress showed preference for one class of producers over another for reasons not defensible by general standards of public health or public good. But the case inevitably raised the larger question of the power of the government to regulate economic activity, and so to constrain economic liberty. It was thus seen as a potential challenge to the vision of government implicit in the New Deal.

Yet despite the apparent constitutional significance of such a challenge, the Court ducked. In its ruling, it essentially refused to review the motives behind the filled-milk law, asserting that the regulation of economic activity did not rise to the level of fundamental rights — and so did not demand the Court's attention, calling instead for deference to the legislature.

Justice Stone's reasoning, set forth in his footnote, rested upon a two-tier theory guiding the use of judicial power. In most circumstances, the Court would defer to the legislature, applying what would come to be known as the "rational basis" test. This "test" would allow for a flexible understanding of large swaths of the Constitution; in the cases to which it applied, the Court would simply ask: Could the legislature have a plausible justification for passing this law? (Almost always, the answer will be yes.) That such a crucial shift in jurisprudence was put forward, in the words of Justice Frankfurter, with the "casualness of a footnote" was indeed odd — but Stone's gloss would nevertheless come to anchor the modern understanding of economic rights in American law.

In a small group of cases involving "personal rights," however, Justice Stone's theory required the Court to subject legislation to much greater scrutiny. But within this select group, liberties such as the right to choose one's profession, or to engage in contracts, were nowhere to be found; they were no longer deemed to be included in the term "liberty" protected by the 14th Amendment. Rather, as Stone put it, legislation would be presumed constitutional unless it potentially violated a right explicitly enumerated in the Bill of Rights; infringed on the democratic process itself; or was aimed at a "discrete and insular minority." These cases would call forth a "more exacting judicial scrutiny," whereby the Court would examine the questionable legislation in detail to ensure that it was, in fact, aimed at a legitimate public interest and did not violate fundamental rights.

Carolene Products — and its famous footnote — recast judicial power as a supplement to the democratic process, and as a dedicated champion of those liberties putatively bound up with it. Political rights were thus placed squarely above economic rights, which were essentially stripped of their substance. The result was that government could discriminate at will against players in the market; it could impose controls not only grounded in some compelling public interest beyond the economic sphere — like consumer safety, or the protection of free speech — but also those intended to privilege the economic preferences of legislators (and therefore the economic interests of constituencies powerful enough to sway legislation to the detriment of their competitors).

In embracing Stone's theory, the New Deal Court rejected a viable, constitutionally sound alternative. The choice the Court faced was not between Stone's vision and laissez-faire non-regulation; rather, it could have endorsed reasonable regulations of economic activity that would fall evenly upon all market players, and that would be aimed at a legitimate public interest — much as the Court protects other forms of liberty. While the free exercise of religion, for instance, is constitutionally protected, the government may still enact laws that happen incidentally to regulate religion — as long as the laws are not intended to target particular religious practices and beliefs. The standard for constitutionality that the New Deal Court could have adopted for cases in the economic sphere, in other words, was that of the neutral law, neutrally applied.

That standard, not coincidentally, was shaped significantly by the "Old Court" the New Dealers so detested. In a series of cases dealing with the relatively new Mormon church and the practice of polygamy in the 19th century, the Court had reasoned that laws could not be aimed at religion itself; this did not preclude, however, the government's incidental regulation of religious practices in the course of carrying out its other functions and responsibilities. The key, as in class-based legislation, was neutrality. A longstanding law that sought, in generally applicable terms, to prohibit polygamy was acceptable precisely because its aim was the preservation of civil marriage — not the harming (or helping) of a particular religion. What the government could not do was prohibit polygamy sealed in a religious ceremony while permitting other cases of it.

Of course, this neutrality principle did not originate with the Old Court; John Locke articulated it in 1689, in A Letter Concerning Toleration. "Whatsoever is permitted unto any of his subjects for their ordinary use, neither can nor ought to be forbidden by him to any sect of people for their religious uses," Locke wrote. But he continued: "those things that are prejudicial to the commonweal of a people in their ordinary use, and are therefore forbidden by laws, those things ought not to be permitted to churches in their sacred rules."

Locke's notion — and the Old Court's embrace of it — have continued to influence the modern Court, at least with regard to religious liberty. For instance, in the 2006 case Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficiente União Do Vegetal, the Court — led by its new chief justice, John Roberts — unanimously struck down a federal law that prevented a "Christian Spiritist" sect from using hoasca (a hallucinogenic sacramental tea) precisely because the law was not neutrally applied. It turns out that the Controlled Substances Act prohibited the use of hoasca while carving out exemptions for the religious use of other drugs (peyote in particular); moreover, the government failed to demonstrate any practical difference between the two substances and hence any reason that the use of one should be permitted and the other banned.

The Court's overwhelming response to the unbalanced, and effectively discriminatory, application of the Controlled Substances Act was hardly shocking: The Court has often acted unanimously when statutes have targeted particular religions and otherwise violated the principle of neutrality. In such cases, the Court must judge whether questionable laws are aimed at legitimate public ends, or are instead being used to favor or punish particular groups.

This question — so central in cases of religious discrimination — is also one courts necessarily confront in deciding cases about economic liberty. A law that treats bakers and lawyers differently — by, say, prohibiting the former from working more than 60 hours a week while allowing the latter to do so — would be justified if allowing a baker to work more than 60 hours posed some risk, either to the worker or to public health, not presented by the case of an overworked lawyer. But without such a difference, that law would be patently unfair. And yet such laws have been routinely upheld over the past half-century.

In Kotch v. Board of River Port Pilot Commissioners (1947), a nepotistic system of appointing river-boat pilots in Louisiana — a scheme under which entry into the market was controlled by the whims of a board, thus preventing most people from entering the profession — was sustained by a divided Court. So was a Michigan statute that prohibited any female from acting as a bartender (unless she was the wife or daughter of the bar's owner) in the 1948 case Goesaert v. Cleary. In the 1955 case Williamson v. Lee Optical, an Oklahoma statute that made it unlawful for anyone but a licensed optometrist or ophthalmologist to fit lenses to a face or to duplicate lenses — thereby denying opticians much of their traditional business — was unanimously upheld. So was a Kansas statute that prohibited debt adjustment by anyone except a lawyer, in the 1963 case Ferguson v. Skrupa.

Some justices, of course, have objected to the Court's rejection of economic rights. But these departures have often been expressed in dissents, and have almost always been in cases where the regulation at stake intruded on some other liberty, usually the freedom of speech. So in the 1961 case Lathrop v. Donohue, for instance, a lawyer required to pay professional dues to the state bar association (a private professional guild) — which might then use his money for political purposes that he opposed — got at least some sympathy from Justices Hugo Black and William Douglas in their dissent. Ultimately, however, the lawyer did not win his case.

RECOVERING ECONOMIC LIBERTY

The New Deal approach to economic liberty, now so deeply rooted in precedent that even most originalists oppose upsetting it, has contributed mightily to the expansion of the Court's power to arbitrarily determine the meaning of crucial constitutional provisions — even beyond the 14th Amendment. Its effects were evident, for instance, in the 2005 eminent-domain case Kelo v. City of New London. In a narrow 5-4 majority opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens pointed to the Court's "longstanding policy of deference to legislative judgments in this field" to elevate the value of general economic development — as determined by a local government — over the protection of individual property rights, despite the limits on government takings made explicit in the Fifth Amendment.

The possibility that restoring economic rights to their original place in our constitutional order might lead to abuses by some in the judiciary is hardly a reason to settle for the status quo. After all, some judges seem bent on having their way with the Constitution, with or without a particular invitation to mischief.

Moreover, the significant government interventions in response to the recent economic crisis have undoubtedly put into the pipeline several cases that could open the door to a more appropriate, and historically accurate, understanding of economic rights. If originalists continue to duck the issue, though, that opportunity will be lost. The Constitution as written and intended, especially the 14th Amendment, treats economic liberty like other fundamental rights — and it is time for the Supreme Court to do the same.

But even though a Court that respects the Constitution's original meaning regarding economic rights could play an important role in forcing these crucial questions to the surface, it is not the place to settle them. If economic liberty is to return to the constitutional fold, it will ultimately require the people — and their representatives — to take such liberty seriously.

Unfortunately, such circumspection appears unlikely — at least for now. Congress and the president have rushed forward with vast new regulations and programs without pausing to consider whether such efforts are constitutionally justified. Congressional leaders, for instance, have pledged to take up the Employee Free Choice Act: an amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act that would effectively eliminate the secret ballot for union-organizing elections and vest the government with the power of compulsory arbitration. Under this proposed legislation, if companies and unions cannot reach agreement on an initial contract after 90 days of negotiation, the government can step in and force both parties to accept the terms that it establishes — which could cover wages and benefits, business operations, hiring and firing, and a host of other management decisions. Is such authority appropriate and wise in our system of government?

In 2009, in the midst of the financial meltdown, the Treasury Department convinced ailing automakers Chrysler and General Motors — which the government was already keeping afloat — to go into bankruptcy as part of the companies' efforts to restructure and reorganize. In the name of speed, the government rushed around existing bankruptcy laws and paid off creditors in an uneven manner. Secured creditors, in the form of bond holders, were pushed aside in favor of unsecured creditors for apparently political reasons. The government may also have twisted the arms of banks that had accepted bailout funds to waive their standing as secured creditors of the automakers, in order to ease this forced rush to bankruptcy. The restructuring of General Motors also left some shareholders with nothing, while the United Auto Workers carried forward a 17.5% stake in the company and the federal government came out "reluctantly" owning 60%. Is the desire to avoid the collapse of a large company sufficient reason to yield such power to the federal government? And going forward, how can the government regulate a company in which it has a majority share?

Congress has also passed legislation that limits executive compensation and bonuses at financial firms that took money from the Troubled Asset Relief Program. On its face, this law does not necessarily pose a constitutional problem if the companies are free to reject government funds. But executives at some of the largest banks have reported that, amid the panic of the 2008 financial crisis, they were effectively forced by government officials in closed-door sessions to take the federal bailouts. And in 2009, when banks wary of the strings that came with TARP tried to start paying back the money in order to free themselves from federal constraints, they were told they could not; the government would dictate when the companies could exit the program, and under what conditions. Can the government force private firms to act, or to accept public money? And can the government refuse to allow firms to pay that money back when they wish?

Such questions of policy and prudence in our democracy have always been informed by constitutional considerations — by the formal structures and boundaries of government authority established by the framers of our regime. But the history of judicial interpretation since the New Deal, which has cast off the limits on Congress's commerce-clause power and read economic liberty out of the 14th Amendment, makes it exceedingly difficult for us now to resort to the framers' views and insights.

Recovering a sense of the importance of economic liberty, then, would not be an act of antiquarianism. Rather, it would be a means of contending with the unprecedented challenges we face today — and with those that are sure to emerge in the months and years ahead. It could deepen our understanding of liberty — and of its counterpart, responsibility — in a time that calls for both. And it could allow us to benefit from the wisdom of our Constitution's framers at a time when we desperately need it.