Are Work Requirements Dead?

The American public has long demanded that welfare recipients, if employable, be required to work as a condition of government aid. In 1996, after this demand had intensified among voters on both sides of the aisle, a Republican Congress enacted, and President Bill Clinton signed, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA). The law, for the first time, imposed serious work tests on the main cash-aid program for families that was once known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and is now called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

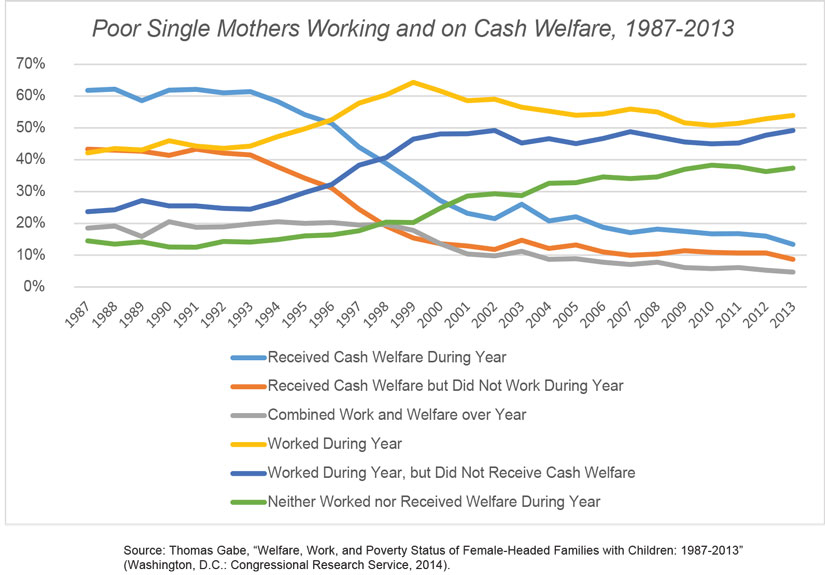

In just a few years, the AFDC/TANF rolls, which had exceeded 14 million people, plummeted to 4 million. Poverty rates also fell, with those for children in female-headed households dropping from 55.4% in 1991 to 39.3% in 2001 — the largest decade-long decline since the early 1960s. At the same time, the share of poor single mothers who worked soared (see chart below), with work replacing welfare as the main income support for these families. After all was said and done, PRWORA became one of the federal government's single greatest victories over poverty among working-age Americans and their children.

After this triumph, many expected lawmakers to extend work tests to other welfare programs, including food stamps (now called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP) and housing assistance. But the expected reforms never materialized, and over time, the rise in work rates halted and even reversed. By 2018, and in spite of a drum-tight labor market, only 30% of poor adults were working at all.

Some short-run political and policy-related reasons help explain this loss of momentum. For one, most experts are no longer interested in building programs, while many of our political leaders have become wholly absorbed in partisan warfare. At the same time, other policy issues have largely displaced welfare reform as a priority for voters. More disturbing than these obstacles to welfare reform, however, is the more permanent — and more substantive — resistance to building up and expanding work requirements.

Despite all the political and circumstantial hurdles to implementing new work requirements for welfare, they remain one of the government's most effective tools for tackling both dependency and working-age poverty. It remains imperative, therefore, that we identify and address the obstacles to additional reform.

POLITICAL HURDLES

Perhaps above all, welfare-reform efforts have died because, for the past four years, Washington was consumed by one topic: Donald Trump. Democrats, for their part, were wholly preoccupied with opposing him. Having tried and failed to remove him from office after the House impeached him in 2019, they carried on their fight by loudly and endlessly opposing the president in Congress, in the media, and on the campaign trail. At the same time, Republicans almost universally defended Trump — a task which, given the president's behavior, became an exhausting, all-encompassing responsibility. In all the furor over Trump's latest press conference or tweet, social-policy issues were all but forgotten. Congress was barely able to keep the government funded and running, let alone agree on any major policy reform.

But there were deeper forces at work, too. The welfare-reform initiatives of the 1990s were chiefly the doing of Republicans in Congress. While some Democrats signed on, especially after seeing how popular reform was with the public, work requirements never enjoyed as much bipartisan support in Washington as they did in places like California or Wisconsin — two states that had led earlier reform efforts.

Making the possibility of a renewed bipartisan effort even less likely is the fact that Democrats have moved well to the left since the welfare-reform efforts of the '90s. In the past, social reformers argued that government must offset economic inequality through increased income protections for the poor. But in those days, left and right alike assumed that in most instances, no barriers to work existed. In other words, they presumed most poor adults were already working — or at least, that they were employable — which was why work requirements were widely seen as fair and feasible. To exempt the poor from employment, one had to make a concrete case that an individual could not work, due perhaps to a disability or other circumstances outside one's control. Even if the economy left the poor with little income, then, most Americans considered them responsible for constructive (or destructive) personal behavior.

Today's left, however, paints the poor as disadvantaged in a much deeper sense. Progressivism presumes that all social problems, including non-work, follow directly from socioeconomic inequality. Thus, the poor need not provide evidence of barriers to explain their lack of employment; their poverty alone suffices to indicate that they are victims of an unequal, unjust society. The public is therefore obligated to support them — and with greater generosity than it does now.

Advocates of this view include Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Democratic representative from New York who has become the leading ideologue of the new House majority. Meanwhile, influential writers outside of government — including Ta-Nehisi Coates, Michelle Alexander, and Nikole Hannah-Jones — push identity-politics narratives that paint America as irredeemably racist and structurally arrayed in opposition to black Americans. Slavery, in this telling, is America's original sin, and American history and politics are principally about race and racism. Society should thus understand poverty and even crime among poor minorities as entirely due to structural inequalities. Accompanying compassion and concern with high expectations — or "tough love," like work requirements — is now seen not as reasonable and fair, but as deeply unjust.

That impulse grew stronger after the killing of George Floyd by the Minneapolis police in May 2020, which triggered a vast protest movement against police violence and racism. Other than reforming or defunding the police, the movement has lacked specific policy goals. But because it has presented racial minorities as victims of white violence and oppression, the idea of expecting poor minorities to work while on welfare has become even less thinkable.

ALTERNATIVES TO WORK-BASED REFORM

Even before the Democratic Party's sharp turn to the left, debate among experts about how to promote work was trending against enforcing work requirements . Left-leaning experts and advocates have long resisted requiring welfare recipients to work on the theory that the low-wage jobs these individuals might acquire would not pay them enough to escape poverty. They argue that welfare beneficiaries should complete high school or even attend college so they can compete for higher-paying jobs, and only then should they face any sort of work test. Effectively, these advocates want to turn welfare into an education scholarship.

This education-first approach to welfare would sound practical were it not for the findings of welfare-to-work experiments of the 1990s. These experiments conclusively showed that programs placing recipients immediately into available jobs, even low-wage ones, outperformed programs that stressed education — that is, they generated more gains for recipients in both employment and earnings. Recipients who pursued education or training programs seldom completed them and rarely found work afterward; only programs that required recipients to take available jobs actually succeeded in guiding them away from welfare and toward independence.

Lately, however, some left-leaning jurisdictions such as New York City have begun re-emphasizing training. They argue that the evaluations from the 1990s are out of date and that, in today's globalized economy, workers without skills will quickly become unemployable. And yet there are still plenty of unskilled jobs available. In fact, prior to the drop in employment due to the pandemic, manual-service and blue-collar industries faced serious labor shortages, and wages in those industries were rising faster than wages for white-collar workers.

Moreover, it is not easy to upskill jobless welfare recipients by sending them back to school. While "sectoral" training programs — those in which skills taught are closely based on what local employers demand — have shown some impact on employment and earning outcomes, these programs tend to focus on workers whose "soft skills" (i.e., the ability to work regularly at any job) are already strong. Consequently, such programs are unlikely to be replicable on a larger scale.

Another long-standing illusion on the left has been the belief that the reason so few welfare recipients seek employment is because wages are too low. If welfare recipients took jobs, proponents of this view contend, they would lose public benefits, leaving them little better off than they would be if they simply remained on welfare. Their proposed solution to this dilemma is to introduce work incentives by reducing welfare benefits only gradually after recipients find employment and their earnings rise. Wage subsidies, too, could make going to work more worthwhile and thus raise work levels.

The left finds this approach attractive because it obviates any need to enforce work requirements. It also honors the liberal conviction that only a lack of opportunity prevents more poor adults from working. If society gives them a better deal, they argue, these adults will work and get ahead without being forced to do so.

Indeed, for decades, economists have believed work incentives could achieve such behavioral changes. The principle incentive of this sort is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), first enacted in 1975, which raises the earnings of low-paid workers with children by as much as 45% (single workers who are not raising children receive much less). Some statistical studies claim that the EITC, rather than the pressure to work stemming from welfare reform, was the main reason why work levels for poor single mothers soared in the 1990s. In fact, a recent National Academy of Sciences study on how to reduce child poverty relied heavily on that belief, claiming that government could raise both the income and work levels of poor families simply by strengthening work incentives like the EITC while expanding other aid programs. Better incentives, the authors argued, would improve worker pay while also coaxing more people into employment. The connection between welfare and work would make reform more effective as well as more popular.

Experimental evaluations of work incentives, however, have always found small or negligible effects on employment. The EITC improves the lot of low-wage workers if they already work, but it rarely makes anyone find work in the first place — and the latter is the key to reducing poverty. The case for a large work effect rests on the statistical studies just mentioned, but these studies are less authoritative than real evaluations, and recently an important paper by Henrik Kleven has questioned most of their findings. Furthermore, firsthand observers of welfare reform did not notice any EITC effect on work levels when the reform was implemented in the late 1990s. What raised work levels far more often was requiring welfare recipients to enter work programs and actually take jobs.

A third and final alternative to enforcing work requirements that some on the left favor is a guaranteed jobs program. The belief persists that the failure of many poor Americans to work must be due not only to barriers or low wages, but to insufficient positions for the unskilled. Yet not since the Great Depression has there been a literal lack of jobs anywhere in the economy at some legal wage. The prevalence of illegal immigration is proof enough that low-paid work is widely available. The Great Recession, lasting from 2007 to 2009, did raise unemployment rates enough to revive fears of a job shortage, but in response, Congress created 260,000 subsidized jobs for low-income adults and youth. These slots were eagerly taken by enough jobless workers to suggest that creating more such positions could help solve the work problem even in more prosperous times.

But surprisingly, even guaranteeing work does little to move jobless and poor adults into employment and financial stability. The only job-guarantee program that has ever raised work levels was a youth-employment program of the late 1970s, which was adopted when private jobs were far scarcer than they are today. Back then, teenagers in school readily took the positions made available through the jobs guarantee, although school dropouts — who were a greater concern — did not. Subsequent job-guarantee programs have drawn only a tepid response. The New Hope Project of the late 1990s, for instance, offered to help jobless Americans find employment, supplemented their earnings to reach at least a poverty-level wage, and provided them with child and health care if they worked 30 hours per week. It found few takers, and long-term work gains among those who did participate were slight.

The Obama administration also ran several experiments with "transitional" jobs programs in hopes that they would raise employment levels among the "hard-to-employ." The target here was not so much non-working mothers on welfare as poor men in arrears on their child-support payments or those leaving prison on parole. Though recipients typically took the jobs, which were temporary, most did not move on to working in the private sector when the subsidized positions ended. The trouble was that the programs were designed by planners who thought enforcing work, as was done under TANF, was passé. Thus, in nearly all the experiments, the jobs offered were voluntary and short-term; mandatory-work programs were not seriously tested.

The outcome of this project and others shows that the mere opportunity to work is not enough to convince most poor non-workers to embrace employment. Rather, what most clearly urges non-workers to take jobs is administrative oversight. The key is requiring those expected to work to enter programs where they have to look for work and start jobs, and where case managers follow up with them to make sure they do. The oversight must be serious, and it must last for the duration of the work requirement.

Unfortunately, many academic experts on poverty have dropped any pretense about work altogether. Enforcement of work requirements violates the liberal conviction that non-work is involuntary, the result of adverse social conditions rather than a non-working way of life. Thus, despite the evidence in its favor, most experts likely never accepted the argument for requiring work in the first place — and are, if anything, even less likely to do so now.

REFORM FROM 40,000 FEET

A major reason why economists continue to propose benefit-oriented, rather than work-oriented, solutions for poverty is that they typically reason through social policy only from a high altitude. They therefore lack any direct knowledge of how anti-poverty programs work — or fail to work — on the ground. They often lack empirical data on this topic as well. Instead, their studies of poverty or welfare are based almost entirely on statistical analyses of data from government surveys. Their correlations may show that if various benefits and incentives are improved, work levels should rise or poverty levels should fall, and because their intentions are good and their mathematics are impressive, policymakers from outside the economic caste tend to credit these estimates.

But economic data do not disclose how programs are implemented locally. Evaluations of actual programs are an improvement over disembodied statistics because they test whether benefits actually reach the intended recipients and have some positive effect. But even when evaluations cover the whole program, they can rarely tell what specific features explain its success or failure. To learn more takes messy field research, where investigators quiz local operators about how they run their programs. Such methods lack the same academic cachet as quantitative research.

Economic methods also presume that the behavior of the poor reflects economizing decision-making. The presumption is that people act so as to optimize their income. But in fact, people (poor and otherwise) often fail to do what sensible economizing seems to require. What changes their behavior more than incentives is public authority: As welfare reform in the 1990s aptly illustrated, simply telling the poor that they can and must work generates more gains in employment than any incentive. Yet such effects are essentially invisible to economists operating from high off the ground.

Why have social scientists failed to develop a clearer picture of these realities? The reason largely boils down to academic incentives. The academy generates many more doctorates than there are jobs allowing graduates to use their rarified skills, so career competition dominates these programs. For researchers just starting out, the surest way to obtain an academic job and then publish enough to achieve tenure is to perform highly quantitative research that showcases technical virtuosity.

As a result, nearly all social scientists who deal with poverty or welfare today are primarily mathematicians. Their work offers little empirical content, let alone institutional findings about program operations that are crucial to diagnosing and solving social problems. This is true even of faculty and students in the public-policy schools, which claim that their mission is to improve public policy. In fact, they have very little to teach regarding actual government, since their main audience is made up of other technicians like themselves.

A similar view of poverty is also naturally appealing to Washington's elites. Just as in the academy, the mood of leading poverty experts inside the Beltway is extremely detached. At Washington conferences organized by anti-poverty specialists, most of the speakers and many members of the audience have a Ph.D. in some technical field — usually economics. The leading figures are typically tenured faculty from major universities, research centers, or Washington think tanks, and the conferences themselves are organized to allow attendees to network and advance their careers. At such events, those actually engaged in policymaking — including congressional staff and executive-branch bureaucrats — count for little.

The presentations tend to be highly technical, with experts making little effort to explain their findings to non-academics. The presumption is that such reasoning contains the key to poverty solutions. This feeds the conceit of the mandarins who advise Congress and executive agencies, who believe that poverty can be beaten by manipulating benefits or payoffs from the center without getting anyone's hands dirty. And doing so supposedly satisfies society's moral imperative to help the poor.

The scholars and D.C. elites who analyze social problems, however, contribute very little to overcoming them. The success of welfare-reform efforts in the '90s was chiefly the doing of modest local and state officials who figured out how to create and manage effective work programs — and they did so mostly on their own. It was they who gave welfare recipients the clear message that work was required and then helped them find jobs to fit those requirements. As one official in Wisconsin bluntly put it, "[i]t's because of us. We are welfare reform." They certainly got their hands dirty, as the academics and Washington elites do not. Their struggles are far less genteel than running regression equations and speaking at major conferences, however, so few of these worthy implementers ever appear on academic panels or before Congress. Nor do they receive much notice or credit for their work.

CONSERVATIVE ILLUSIONS

Not all the opposition to work requirements comes from the academy, or even from the left. Conservatives in politics and government also resist engaging in the kind of local programming needed to make work a reality on the ground.

What made PRWORA's work requirement credible in the 1990s was that, beginning under the Reagan administration, many states had experimented with tougher work tests under AFDC. In 1988, the federal government mandated that all states induct more welfare recipients into work programs. Not by accident, the states that chiefly led reform — California and Wisconsin — had strong pro-government traditions and were especially skilled at work-program development. Thus, when Congress sharply raised work standards in PRWORA, it was already clear that most states could and would enforce such standards. Realizing that, most of those on welfare left the rolls for jobs without much prompting. If those local work programs had not been in place, merely enacting new nationwide requirements would not have changed much of anything.

The story has been the same in Europe. Most American poverty experts — especially those on the left — think Europe is much more generous to poor families than America and less eager to put them to work. Many recommend we adopt that model here. But this social-democratic image is outdated; all the major European countries have since concluded that passive poverty is a danger to their societies. In recent decades, they have moved toward curbing dependency and requiring work of the employable poor. Common changes among European nations include subjecting more income programs to work tests and shifting responsibility for the programs from national to local governments. In doing so, they have been much more patient with the administrative demands than Americans typically are.

For most American conservatives today, however, improving the welfare system is a low priority. Many of them believe that to do so is to perpetuate an institution that promotes poverty. The main goal of reform, they argue, should be to abolish welfare. In the eyes of these individuals, reform should be required only once: Tell recipients to work, and dependency will take care of itself. Indeed, PRWORA promoted that idea by allowing states to meet the new work standards simply by reducing their caseloads without directly promoting employment. That was why the act did not require the maintenance of the earlier work programs. The conservative hope was that, as caseloads fell, government would be downsized as well.

But this is just as much an illusion as the liberal fantasy that higher benefits and incentives alone can raise work levels. The public rightly demands that some aid be given to the destitute, even those who are employable; an effort to enforce work within welfare, therefore, cannot be avoided. Throwing the dependent off welfare is not sufficient to encourage work, either. In a rich society, the needy have many ways of surviving on irregular sources of income — including charity, help from friends or relatives, and child support — without working or going on welfare, but at a cost to society nonetheless. The fact that welfare can promote work may be the most useful thing about it. Children need some minimum income to thrive as well — if not at the cost of work.

In light of their proven effectiveness, mandatory-work programs that existed in AFDC/TANF must be recreated. Better still, they must be extended to employable recipients in all welfare programs and to jobless men of working age — especially those owing child support and ex-offenders on parole. The heavy involvement of low-skilled men in drug gangs and street crime is America's most acute poverty problem; shifting these men into steady employment is thus arguably the most urgent task in all of social policy.

TAKING RESPONSIBILITY

In recent years, Democrats have been the most averse to enforcing work requirements. But looking back to preceding decades, it becomes clear that both parties have abandoned leadership when it comes to America's work problem.

After Ronald Reagan's presidency, extremism of either the right or left became unpopular with the public, giving both parties incentives to display moderation. The early adoption of work programs, therefore, became a bipartisan effort. Republican President George H. W. Bush was the first to seriously implement work requirements at the federal level in the late 1980s, while Democratic President Clinton signed off on the radical reforms of 1996 and implemented them well. As a result, both parties were able to claim credit for the massive drop in welfare rolls and the surge in work levels that resulted.

But since then, the much-noted polarization of the parties has intensified. When they take up policymaking at all, Republicans push for cuts in spending and taxes while Democrats resist these cuts or propose still more spending. The work-requirement issue does not serve either party's agenda because it argues for changing the nature of government far more than its size. The major change required for work-based reform to succeed is not to do more or less for the poor, but to demand their employment in return. As a result, the work discussion has been lost in the shuffle. The right may be content with the fact that past reforms sharply cut cash welfare while the left is content that work tests have not been extended, but neither side has fully addressed the work problem.

Partisan battles seem always to put principles at stake. The temptation is to go all out for what seems right — to get into heaven, so to speak. But in politics, as Max Weber wrote, such an "ethic of ultimate ends" is at war with the statesman's "ethic of responsibility." Those who truly lead must do what solving public problems actually requires. And real solutions always necessitate moral compromises, where some people are coerced or denied and not all values are served. Crafting work programs plainly falls into that category. It is a difficult business, easy to criticize, and justified only by the effort and order it generates. Our leaders once faced up to that responsibility. Today, they do not.

In this respect, the need to emphasize work poses for our leaders a sort of challenge similar to the one it poses for the poor themselves: It calls for taking obligations and responsibilities seriously. Imposing obligations on those who benefit from public assistance demands a certain attitude toward our role as citizens as well.

We think of America as a free country, yet to be truly part of America and accepted as such, one must do more than claim rights and benefits; one must also shoulder the characteristic burdens of freedom — which include, pre-eminently, graduating from school, obeying the law, and working for a living to the extent that one can. We like to imagine that freedom itself is enough to promote all these disciplines: All people need is opportunity, and they will be motivated to display the virtues that getting ahead requires. Society, therefore, need not promote those virtues. On the left, advocates assume that some new benefit can magically enable non-workers to overcome barriers, empowering them to work without urging. On the right, conservatives accept that work requirements must be enforced, but they want the urging to be done by the private sector, not by government.

If work is essential to society — and it is — we must finally treat it as an end in its own right. It must become a centerpiece of social policy rather than an afterthought. And to achieve it will require what Weber called the "strong and slow boring of hard boards" — the ongoing, at times painstaking, but utterly essential effort of statecraft.