Are Our Parties Realigning?

Strange things have been happening in Western democracies over the past few years. The British are leaving the European Union. Catalonia is again pursuing independence from Spain. Italy's promising young prime minister, Matteo Renzi, lost a debate about his proposed constitutional reforms, prompting him to resign in 2016. In 2017, the far-right Alternative for Germany party won seats in parliament. Later that year, the far-right Freedom party helped form Austria's new coalition government. Even in France, where Emmanuel Macron won the presidency in 2017 and the economy is growing, the centrist leader's popularity fell to 40% a year after his election. And of course, Donald Trump is president of the United States.

We live in an age of electoral and political instability. And in our country, this has led many observers to wonder if our democracy can survive. Some pundits and professors have argued that the country is headed toward tyranny or fascism. (A Google search for "Trump and Hitler" produces millions of results.) Others have declared that the Republican Party is divided and done, that the government is broken, and that the U.S. has lost its leadership role in the world.

No one can know the future, and these prophets of doom cannot simply be dismissed. We can, however, know the past. And America's history suggests that times of intense and uneasy transition can often feel like utter breakdown, in large part because of how our system of government interacts with our way of doing politics. Simply put, our sense of stability is often the result of an equilibrium in our party system, while a sense of uncertainty and chaos often accompanies periods of change within and between our political parties.

One way to understand the politics of this period, therefore, is to consider it through the lens of our parties and their coalitions. What we find when looking through that lens offers no guarantees of the future, of course, but it does suggest some reasons for confidence in our system, even in an era of global change.

SHIFTING COALITIONS

The framers of our Constitution, in producing a new outline for the national government in 1787, made no mention of any role for parties in that system. Their writings at the time suggest they might have hoped that none would emerge. But any such expectations were soon dashed. Life under the new Constitution rather quickly confirmed the need for some sort of political organization to manage and facilitate coalitions.

The first American political parties formed as a result of Alexander Hamilton's efforts to pass controversial measures such as funding the defaulted Revolutionary War debts of the states, ratifying a pro-British treaty, and chartering a Bank of the United States. To secure the passage of that program, Hamilton and his allies created a permanent congressional faction that was labeled the Federalist Party. This group's success in the early 1790s predictably resulted in the organization of a counter-faction called the Republicans, led by opponents like James Madison and Thomas Jefferson. These parties began to structure the electoral process by selecting candidates for office and running the polls on Election Day.

Political parties served their most important function by providing cues or guidelines that individual voters could use in interpreting complex political events and in making numerous electoral decisions. While the founders had envisioned a democratic ideal, in practice few voters had the time, inclination, information, or intelligence to understand the issues of the day or to assess individually the candidates seeking their votes. Parties greatly simplified these matters. Candidates ran under party labels, which voters could associate with certain issue positions and with which they could personally identify. By the time of Andrew Jackson's second term, the United States had a competitive party system featuring two broad-based, fairly decentralized, national parties. With the notable exception of the Civil War era, that pattern has persisted until the present. But at crucial points, the parties have changed their electoral bases in response to significant changes in the circumstances that underlie and ultimately shape our politics.

Creating stable electoral bases allows parties to coordinate interests across institutions, which, in turn, enables government to function and the economy to operate. Since what is stable today may not be tomorrow, parties and candidates periodically create new majorities, which are stable for a time. In the Civil War era, the new Republican Party adopted the slogans and arguments of abolitionists and the recently defunct Free Soil Party to fashion a winning "free men, free soil, free labor" philosophy, which created a new Republican majority.

The great transformation of the world economy in the industrial age generated a set of challenges much like today's: immigration, inequality, the role of corporations, and so on. The Republican Party of President William McKinley, House Speaker Thomas Reed, and McKinley supporter and businessman Marcus Hanna won laborers, Midwestern farmers, and business interests, creating a new coalition to meet those challenges. This coalition endured until roughly the New Deal. The breakdown of the world economy in the late 1920s led to the creation of a new, stable Democratic majority consisting of labor, agriculture, the poor, the South, and components of the middle class, which, at least in Congress, dominated from the 1930s until the 1990s. There were changes in this system as Presidents Kennedy and Johnson brought minorities into the Democratic Party, ultimately costing the party its solid support from the South.

Again and again during periods of instability, political parties have adjusted to find a new equilibrium. Old factions disappear: Pro-silver Republicans, for example, ceased to exist after 1896, as did segregationist Democrats in the latter half of the 20th century. The new stable majorities thus generated have brought periods of rough equilibrium between elections, institutions, and policy.

For example, prior to the 1932 election, Franklin Roosevelt and his Democrats responded to the crisis of the Great Depression by promising programs to make people free from fear of economic ruin. Republicans, by contrast, resisted such welfare promises, claiming the government could do little about the effects of the Depression. This "welfare-or-no-welfare" debate was resolved with the Democratic victory and subsequent re-elections, which forced the Republicans to move from the party of "no welfare" to the party of "less welfare than the Democrats" — engendering a new party and policy equilibrium. This sort of party realignment is generally the result of some crisis that generates political instability, which in turn forces the parties to change.

THE ERA OF PARITY

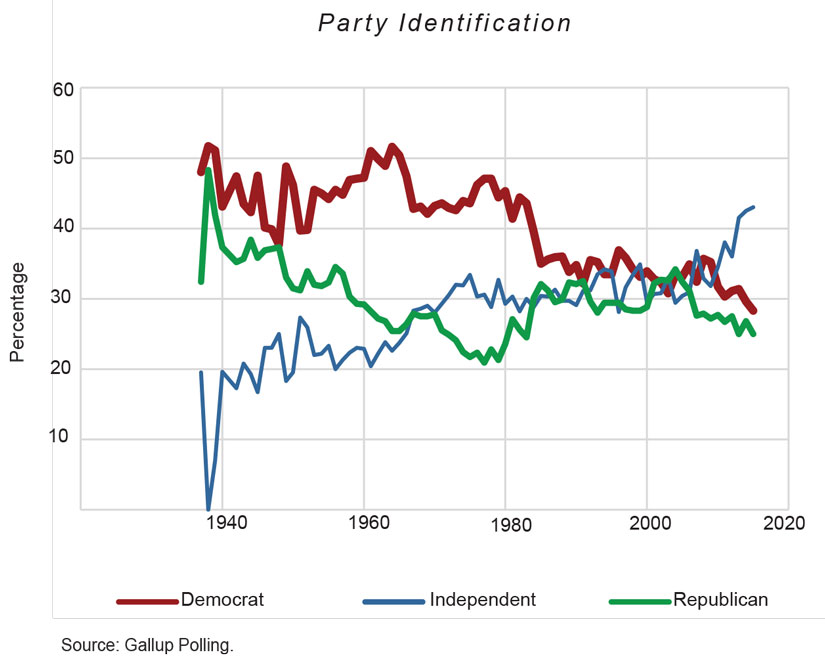

The present American party system has its origins in the 1980s. The figure below shows the Gallup distribution of party identification from 1937 through 2017. The Democrats in the New Deal era began with a lead over Republicans in an electorate with few independents. Though this lead narrowed over the post-WWII period, after the 1958 recession, Democrats opened large margins over Republicans again and, until the Vietnam era, maintained that lead. The Vietnam War hurt the Democrats' margins, but Watergate brought those margins back for a time, so that going into the 1976 and 1980 elections, Democrats had leads of close to two-to-one over Republicans.

Ronald Reagan's victory in 1980, driven largely by the "misery index" (unemployment plus inflation), did not, given the recession and stagflation, change much at first; in fact, Reagan and Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker pursued policies that initially increased unemployment. But by the mid-1980s, a new pattern had emerged: Democrats and Republicans were closer than they had been in over a century, each claiming about a third of the electorate, and the number of independents had increased to plurality status. This pattern has persisted from the mid-1980s to the present. The new party system is one of rough parity between Republicans, Democrats, and independents.

In a sense, the 1980s saw the membership of the two parties sorted by ideology. In 1980, 35% of the population were self-identified conservatives. Of that group, 41% were Democrats, 24% were independents, and 35% were Republicans. But by 1990, just over 20% of self-identified conservatives were Democrats, while over 50% were Republicans. (The group's overall proportion had changed only slightly, at 37% of the population.)

This sorting of conservatives from Democrat to Republican, and its smaller counter-sorting of liberals from Republican to Democrat, proceeded apace over the subsequent two decades. Thus, by 2016, some 85% of Democrats were moderate or liberal and almost 95% of Republicans were either moderate or conservative — and in both parties, the ideologues outnumbered the moderates. This ideologically sorted system replaced the New Deal coalition in which both parties had conservatives and liberals in their ranks.

Remember that the key civil-rights bills of the 1960s were strengthened and passed by Republicans in Congress. In 1976, Reagan offered the vice presidency to Richard Schweiker, the moderate senator from Pennsylvania, to attract liberal Republicans at the convention that year. But in the post-1980 era of parity, Republicans and Democrats do not cooperate on civil-rights issues, and Republican presidential nominees don't select liberal vice-presidential candidates for running mates.

The sorting and subsequent polarization of the parties has generated three important consequences: partisans of each party misperceiving those of the other; presidents who are dividers, not unifiers; and very close elections. In June 2016, Pew found that a majority of Republicans considered Democrats to be closed-minded, while large pluralities of Republicans said Democrats were immoral, lazy, dishonest, and unintelligent. Democrats reciprocated by holding the same view of Republicans: closed-minded, dishonest, immoral, unintelligent, and lazy. Moreover, the politically engaged members of both parties have even more negative views of their counterparts. Political polarization is no longer just about policy differences but now shapes how partisans understand each other as human beings.

George W. Bush and Barack Obama both wanted to be unifiers, not dividers, but the partisan climate, given sorting and polarization, simply made it impossible. One way to use the data we have to consider presidents on this unifier-divider scale is to subtract a president's approval rating among members of the other party from his approval in his own party — the higher the score, the greater the disunity the president engenders; the lower the score, the higher the unity. Bush's score for his first year was a reasonable 43; Obama's score was higher at 62; and Trump's score was 80. Prior to the Republican takeover of the Congress in 1994, presidential scores in the first year were generally much lower: Eisenhower scored 31, Kennedy 29, Johnson 20, Ford 28, Carter 26, H. W. Bush 28, and Clinton in the 40s.

It is true that, over a president's term of office, time intensifies the partisan differences. But recent presidents have been much more divisive figures than their modern predecessors were, even in the later years of their terms. The highest disunity score under both Obama and Bush was 76. Trump exceeded even that with a first-year score of 80. The three of them hold all of the top 10 scores for disunity measured this way.

Presidential elections from 1952 through 1992 were won, on average, by over 10 points. Even when discounting the 1964 and 1972 landslides, the average is still over eight points. Of these 11 elections, five were won with at least 55% of the vote for the winner, and, in eight of them, the winning candidate had at least 50% of the vote. The six post-1992 presidential elections have been won, on average, by about three points and, in two cases, the winner lost the popular vote. No candidate has won with 55% or more.

The picture in Congress looks much the same. In the 21 House of Representatives classes elected from 1952 until 1994, the majority party averaged an 85-seat margin and, of those classes, 20 of 21 were controlled by Democrats. In seven Houses, they held a 100-seat edge. In the 12 Houses elected from 1994 until now, by contrast, the average margin is 35 seats; over those 24 years, Republicans have controlled in 20 years, and Democrats in four. In the Senate prior to 1994, the average seat margin was 57 to 43, with the Democrats controlling in 34 of 42 years. In contrast, the post-1994 seat margin is only 53 to 47, and over those 24 years, Republicans controlled 14 to the Democrats' 10. Clearly, elections at the national level are much more competitive in the party-parity era than they were previously.

In addition to these features, the new party-parity system has created a Congress in which the levels of party voting or polarization are very high. Political scientists employ a measure of "overlapping voting" to get a sense of partisanship in Congress. A moderate Republican might vote with some Democrats 10%, 25%, or 50% of the time, while some moderate-to-conservative Democrats might likewise vote with some Republicans at a similar level, and by looking at the frequency of such levels of overlap we can get an idea of the degree of party polarization.

The results are quite clear: Overlapping voting rises in the late 1930s in the House and earlier in the Senate (due to farm-aid bills), peaks between 1950 and 1970, and is essentially gone by the end of the Reagan era. In sum, the overlapping voting typified by cross-ideological groups — such as the conservative coalition of Republicans and Southern Democrats on economic issues — has been eliminated during the party-parity era. Thus, another consequence of the new electoral-parity system is a return to the polarized voting of the pre-WWII era.

The net effect of the new party-parity system is that parties have few short-term incentives to cooperate in policymaking. Rather, as political scientist Frances Lee has argued in Insecure Majorities, the parties now devote much more energy and time to winning control of the government. This is in contrast to the preceding half-century, when Democrats were the majority, Republicans were the minority, and little collective action was spent on building or preserving majority status.

The new competitiveness drives members and parties to engage in actions that promote their party's image, undercut the image of the other party, and polarize opinion rather than seek compromise. As long as both parties have a shot at majority status, bipartisan cooperation is less likely to emerge. Thus, we have arrived at a new equilibrium where party parity divides citizens, ties up the Congress, and gives us Trump as president.

The patterns of turnover in House, Senate, and presidential elections further clarify the unstable politics of this period. In 1988, George H. W. Bush won the presidency, giving Republicans their third win in a row, although the House and Senate remained Democratic. This extended an era of mostly divided government begun in the 1950s. When Bill Clinton won in 1992, with Democratic majorities in Congress, it was hailed as an end to gridlock — the first of many times in the past three decades when observers heralded the emergence of a new pattern. But in the first of many disappointments for such predictions, that unified control lasted all of two years, until Republicans won control of both houses of Congress in 1994 for the first time in 40 years (and only the third time in 64 years).

Clinton was assumed to be a one-term president, but he easily won re-election in 1996, while Republicans retained control of Congress. This instituted what some viewed as a new era of divided government: Democratic presidents and Republican Congresses. But that prediction soon failed, too. The 2000 elections brought full Republican control of the elected branches for the first time in five decades. And after the 2004 elections, some claimed a realignment, with comparisons to the McKinley era.

This, too, was short-lived, given the Democrats' sweep of Congress in 2006 and their winning control of the elected branches in 2008, which led, among other claims, to James Carville's book entitled 40 More Years: How the Democrats Will Rule the Next Generation. Apparently, generations are shorter than they used to be, since the Republicans handily won control of the House in 2010 and the Senate in 2014. Then came 2016, when, against all odds, Trump won the Electoral College and Republicans maintained control of Congress.

The only pattern in this era has been the lack of a pattern. The last time in American history when such flip-flopping occurred was during the final period of industrial development, between 1874 and 1896 — and, as we shall see, that precedent might teach us something.

THE STRUGGLE FOR THE GOP

The election of Donald Trump was even more of a blow to any expectations of a new equilibrium than the back-and-forth elections of the prior decades. Not only was he not a standard Republican on free trade, taxes, entitlements, and so on, but the Republicans in Congress did not expect him to win. Their reaction to his victory was to try to pull together and pass the legislation they thought mandated by their 2010 wins six years earlier: end Obamacare, reform taxes, cut regulation, and increase energy production, among other longstanding Republican agenda items.

But the narrow Senate margin and Trump's lack of policy knowledge and legislative skill left Republicans with only a tax-bill victory. Obamacare is still the law of the land; immigration reform and budget policy remain problematic; and Trump is a more divisive president than either Bush or Obama. Thus our system — already burdened by partisan divisiveness, close elections, and few incentives for parties to cooperate on public policy — is saddled with an inexperienced, chaotic president and a governing party with no clear sense of what it wants or what voters want.

One result has been a struggle to define the GOP, which has sometimes seemed like a fight between the party's longstanding priorities and some of President Trump's particular emphases. But the battle lines have not been very clear — especially since neither the practical and contemporary meaning of the party's longstanding priorities nor Trump's beliefs are actually all that clear at this point, and since disputes about the president's character often overshadow internal policy debates.

If Republicans lose one or both houses of Congress in 2018, then the battle lines could be drawn more clearly, because those congressional Republicans who have held back criticism of Trump in order to pass legislation will no longer need to restrain themselves in the battle for the party. The 2018 and 2020 election cycles will, by and large, shape what Republicans become post-Trump. Republican incumbents might buy into Trump's views on immigration, deficits, trade, and so on to appease the Trump base, and thus change the party. Or the battle between Trump-like candidates and traditional Republicans could yield a new set of internal divisions and patterns. Or traditional Republican views might come to be reaffirmed.

The dimensions of the battle are revealed in survey data that YouGov has collected over the past few years. Starting in May 2015, they interviewed a panel of 5,000 Americans 17 times, with more interviews scheduled prior to the 2018 elections. The results have shown that Trump voters, compared to those Republicans who voted in the primaries for other candidates, are older, whiter, less well-educated, have lower incomes, and are disproportionately from the Southern, border, and Midwestern states. They are also, on average, angrier about politics, more likely to believe that many in the government are crooks, and more dissatisfied with government. They are very anti-trade and anti-immigration and favor taxing the rich (those making over $250,000).

When asked about illegal immigrants living in the U.S. now, 70% of Trump supporters said they should be required to leave, while less than 35% of other Republicans agreed. In fact, a slight majority of other Republicans thought that they should be allowed to stay and acquire citizenship. On social issues such as gay marriage and the death penalty, Trump supporters were much more conservative than their fellow Republicans; in fact, a majority of other Republicans opposed the death penalty. In the post-election surveys, by a two-to-one margin, Trump Republicans favored a Muslim ban, while other Republicans opposed the ban. The battle for the heart and soul of the party is underway.

While these issues will be important, perhaps even more important is the extent to which Trump Republicans and other Republicans differ regarding the president. The August 2017 YouGov re-contact survey showed that 92% of early Trump supporters liked him, with 72% liking him a lot; Republicans who weren't early supporters, however, liked him less, with only 29% liking him a lot. The president's ability to retain the support of his base means those Republicans running for Congress must face the delicate task of appealing to that base in both the primary and general elections. Ed Gillespie's run for governor of Virginia in 2017 was an excellent example of such balancing. As one Washington Post article put it a few days before the election, "Gillespie is at the center of a civil war that is dividing his party, one pitting the Republican establishment he personifies with his four-star credentials against the anti-Washington forces that propelled President Trump's rise."

The battle between the Trump wing and other Republicans will play out numerous times over the next two election cycles, and the future of the party hangs on who wins. Crucial to Republican success will be suburban independents and Republican women who chose Trump over Hillary but today do not like the president. Off-year election turnout numbers in Virginia and Alabama confirm the importance of these voters.

THE RACE TO REALIGNMENT

In American political science, the standard party-change model has focused on "realigning elections," wherein one party achieves dominance that lasts long enough to resolve the key issues generated by the instability of the era. Those issues, in our time, appear to be challenges like immigration, inequality, family and social breakdown, worker insecurity, automation, trade, America's role in the world, and environmental challenges, among others.

Some observers suggest that Democrats have the best chance to arrive at a formula that captures a durable majority on most of these issues. As of this writing, the 2018 generic congressional poll favors Democrats by seven points (according to the RealClearPolitics average), and Trump's popularity is low. Historically, presidents in their first term often lose seats at the midterm election. And winning the House, the Senate, or both in 2018 would be seen as a harbinger of winning control of the government in 2020.

Control of all the elected branches would give Democrats a base of support from which to reduce inequality, reform the immigration system, and restore American leadership in the economic realm, on the environment, and in other respects. Nice scenario, if you ask any progressive. But there are many reasons why the Democrats are likely to fail in their efforts to create a new stable majority. The first and most obvious is that Democrats, like Republicans, are badly split on how the party should respond to both the Trump presidency and the dominant issues of our time. The result is that the number of Democrats running for president in 2020 may well be in the double digits, creating divisions that resemble those the Republicans faced in 2016.

Second, potential candidates are already favoring policies, like Medicare for all and free tuition, that even Californians know are not affordable. These views don't actually represent today's Democratic coalition all that well. In YouGov surveys, Democrats, by over two-to-one, favor cutting spending over raising taxes to balance the budget, and by almost two-to-one, they believe that quite a few in government do not know what they are doing. In regard to free tuition, 40% of Democratic voters are either against it or are not sure that it would work. Thus, the Democrats have not achieved agreement within their party regarding policies that deal with today's core challenges, and a multi-candidate presidential primary is not likely to resolve the issues and create a stable majority. That leaves the Democrats, like the Republicans, divided and not unified, and, just as with the GOP, the necessary changes seem more likely to occur in primary and general-election contests over the next few electoral cycles. The Democratic Party does not look ready to step up; the Republicans don't either.

Here again, a student of history would be reminded of the closing decades of the 19th century, when there were pro-silver Republicans and pro-gold Democrats (like President Cleveland) and the same intra-party mix on tariffs and immigration and many other prominent issues. Control of the government shifted back and forth between these unsteady parties over and over again. But by 1896, the sorting of the parties had occurred, and Republicans were pro-gold, pro-tariffs, and so on, while the Democrats under William Jennings Bryan were the opposite. The electorate, in that case, chose Republicans, and the ensuing stability gave rise to economic growth and a period of prosperity.

A broadly similar transformation is very likely in our future. The sorting process in the Republican Party has begun, with the Democrats to follow in 2020. This time the sorting will not be conservatives to the GOP and liberals to the Democrats, since that has already occurred and has defined the very order that is growing exhausted. Rather, the coming era will be defined by questions like what do conservatism and liberalism mean to Republicans and Democrats, and which vision will the American people support? Whichever way it turns out, the parties have finally begun the process of adjusting to the realities of the new global economy.

The shapes our parties are likely to take might be easier to see if we consider their most extreme possible forms — which aren't where we will end up but can show us the contours of possibility. For Republicans, these are the possible alternatives on either pole: a Trump-like Republican Party that is anti-immigrant, protectionist, anti-gay marriage, dependent on entitlements, white, old, not well-educated, and concentrated in the southern and central United States; or a party that favors markets and smaller government, and is not anti-immigration per se but is, rather, more libertarian and diverse in membership.

The Democrats, likewise, face a similar polar choice: a Bernie Sanders/Elizabeth Warren Party that pushes socialist-leaning policies (Medicare for all, free tuition, a smaller military, higher taxes, and more regulation) joined to an identity politics that excludes moderates from swing states; or a Democratic Party more like that envisioned by the Clinton-era Democratic Leadership Council, which is center-left on economic policy, inclusive on social issues, relatively moderate on defense and immigration, and somewhat resistant to identity politics.

The battles between these alternatives have already begun in some primaries. And the likely outcome is not any of the polar opposites, but a shuffling of the issues that gives shape to complex coalitions.

UNDERSTANDING INSTABILITY

While we cannot know which way the parties will re-sort, it is clear that the old Democratic and Republican alignments are under stress and are changing as we speak. When a party system is in transition, it induces a collective unease about the future direction of the country. Many observers have been too quick to assume that our political institutions, as opposed to the party coalitions, are broken. The decline of normal order in the Congress, to take one prominent example, was an adaptation to political sorting that allowed the institution to adjust to the stronger pressures of polarization. The regular congressional order worked for the more heterogeneous party-coalition structure of the post-war era, but was ill-suited to the obstructive tactics of the current, more-polarized period.

We will not regain stability by returning to old rules that do not fit contemporary politics. Instead, our party coalitions must respond more adequately to the modern policy challenges of globalized trade and increased automation, inequality, and migration across borders — and our institutions must then follow their lead. Donald Trump's disruptive victory was enabled by one party that marginalized disadvantaged voters in favor of the highly educated winners in a globalized world, and another that offered only cultural comfort as a balm for pro-business policies. Neither of these coalitions seems very stable at the moment.

But there is a big difference between a democracy in the process of sorting out its political coalitions and one that is falling apart because it does not provide the institutional framework and democratic values for working things out. Democracies cannot and should not resist change. They need to enable it to proceed freely and fairly. That's what our party coalitions do. And it seems to be what they are doing now, in their usual messy and uneasy ways.