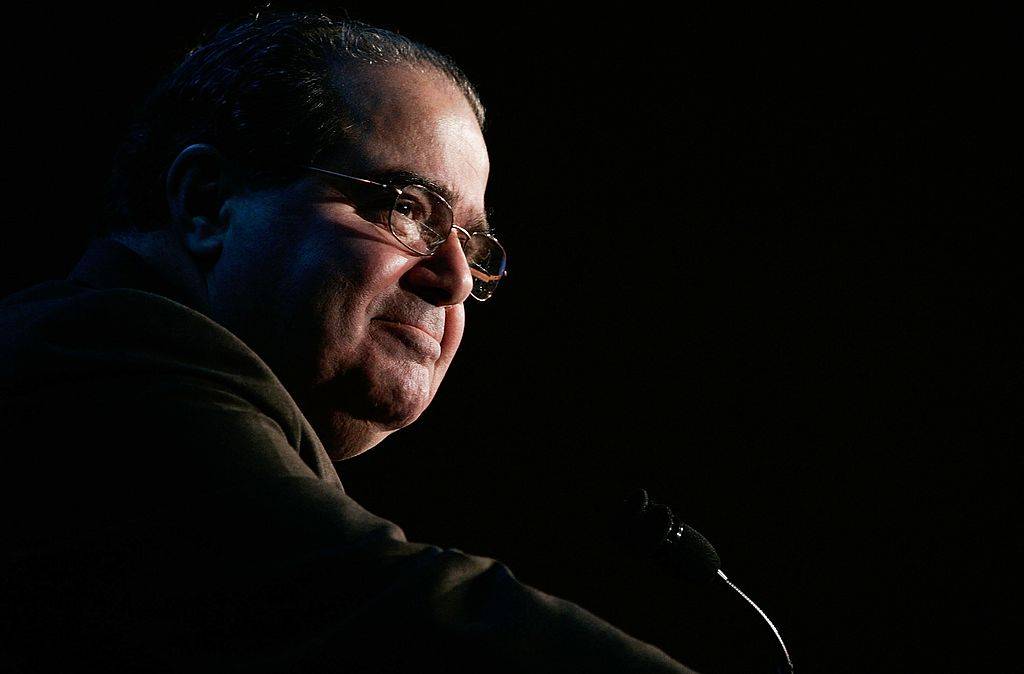

Antonin Scalia, Legal Educator

"Who do you think I write my dissents for?" Justice Antonin Scalia posed the question to a reporter from New York magazine. In the course of a surprisingly candid 2013 interview, she had asked Scalia about the sharp tone of his judicial opinions, pressing him on the effect that his opinions might have on his colleagues. But Scalia pressed the reporter, in turn, to look beyond the Court for his true audience.

"Who do you think I write my dissents for?"

"Law students," the reporter answered.

"Exactly," he replied. "And they will read dissents that are breezy and have some thrust to them. That's who I write for."

Justice Scalia was reiterating a point he had made on many occasions, before many audiences. "He used to say that students were one of his target audiences," Justice Elena Kagan recalled in her contribution to the Harvard Law Review's remembrance of her late colleague and friend. "[A]nd, if my hours teaching administrative law are in any way typical, he had an unerring instinct for what would persuade them or, at the very least, make them think harder. Justice Scalia's opinions mesmerize law students."

In a lifetime of educating American lawyers — in judicial opinions, articles, and lectures — Scalia often spoke directly to the state of American legal education itself. On some occasions, he reached these issues expressly and bluntly, and there is much to learn from those particular writings.

But elsewhere his criticism of modern legal education was subtler, and it went beyond matters of mere judicial methodology. As important as originalism and textualism are, Scalia was pressing a much more profound truth: namely, of the fundamental importance of religious faith and civic virtue in a republic, and the dangers of stripping that moral foundation away from the education of all citizens — especially lawyers.

TWO CRITIQUES OF LEGAL EDUCATION

In a career marked by famous dissenting opinions, one of Justice Scalia's most famous dissents was his departure from modern conventional wisdom in legal education. And, as with so many of his dissents, he reveled in the act. "I go to law schools just to make trouble," he once told an academic audience in Brazil. "I give lectures and stir up the students. It takes several weeks for their professors to put them back on track."

As it happens, I experienced his enthusiastic disruption firsthand. In 2003, I took a break between summer law-firm jobs to travel to Colorado, where I attended the Federalist Society's biennial course that Scalia taught with Professor John Baker. In a group comprised mainly of practicing lawyers, Justice Scalia took special care to interact with the scattered law students. A few months later, when I saw him at another event, he recognized me and asked if I had brought my new knowledge of constitutional separation of powers back to my law professors. "Yes," I told him, "but I have bad news. The professors overruled you unanimously." He laughed — not because he was surprised, of course, but because he wasn't surprised at all.

Justice Scalia's criticism of modern legal education was well known, and well founded. In his 1997 book, A Matter of Interpretation, he began a defense of textualism by diagnosing why too many judges and lawyers pay too little attention to the words of written laws: "The overwhelming majority of the courses taught in that first year, and surely the ones that have the most profound effect, teach the substance, and the methodology, of the common law....American lawyers cut their teeth upon the common law."

To be clear, in critiquing "common law," Scalia had in mind not the classical common law of Blackstone, but rather the modern "realist" reconceptualization of common law, made famous by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. — a distinction that Scalia would sometimes highlight in judicial opinions. "At the time of the framing," Scalia observed in a 2001 opinion, "common-law jurists believed (in the words of Sir Francis Bacon) that the judge's 'office is jus dicere, and not jus dare; to interpret law, and not to make law, or give law.'...Or as described by Blackstone, whose Commentaries were widely read and 'accepted [by the framing generation] as the most satisfactory exposition of the common law of England,'...'judicial decisions are the principal and most authoritative evidence, that can be given, of the existence of such a custom as shall form a part of the common law.'"

Even if, as Scalia added elsewhere, classical common-law judges were aware "that judges in a real sense 'make' law," those judges, Scalia emphasized, would still "make it as judges make it, which is to say as though they were 'finding' it — discerning what the law is, rather than decreeing what it is today changed to, or what it will tomorrow be." In the aftermath of Holmes's "hyperbolic" critique of that approach, however, self-styled "realists" on the bench would approach common-law judging from precisely the opposite mindset, such that common law would be "self-consciously 'made' rather than 'discovered.'"

"This is the image of the law" — the modern common law, as "made" by willful Holmesian judges — "to which an aspiring American lawyer is first exposed," Scalia observed in A Matter of Interpretation. And this approach, he urged, is hardly conducive to the education of American lawyers who will interpret the written laws of statutes, regulations, and, of course, the Constitution. The American law student "learns the law, not by reading statutes that promulgate it or treatises that summarize it, but rather by studying the judicial opinions that invented it."

In their casebooks, students see judges — and envision themselves — working not only to apply law to facts, but also (as Scalia emphasized) "to make the law." Indeed, law schools present the judge as not just making law, but as making "the 'best' legal rule" among many possibilities, and among many seemingly relevant but conflicting precedents. "Hence the technique — or the art, or the game — of 'distinguishing' earlier cases," which is best compared to a football player "running through earlier cases that [leave] him free to impose that rule: distinguishing one prior case on the left, straight-arming another one on the right, high-stepping away from another precedent about to tackle him from the rear, until (bravo!) he reaches the goal — good law."

This sporting metaphor, the halfback's "broken-field running," depicts vividly the law-school realist's notion of a judge as effectively unconstrained — or, that is, a judge constrained only by those who might wrestle him to the intellectual ground. Scalia warned that while the allure of this vision is obvious, less obvious are its lamentable ramifications:

What intellectual fun all of this is! It explains why first-year law school is so exhilarating: because it consists of playing common-law judge, which in turn consists of playing king — devising, out of the brilliance of one's own mind, those laws that ought to govern mankind. How exciting! And no wonder so many law students, having drunk at this intoxicating well, aspire for the rest of their lives to be judges!

Justice Scalia pressed this criticism throughout his career; indeed, when he and Bryan Garner published Reading Law in 2012, he once again introduced the subject of textual methodology with the same indictment of legal education: "Besides giving students the wrong impression about what makes an excellent judge in a modern, democratic, text-based legal system, this training fails to inculcate the skills of textual interpretation."

But while this was Scalia's primary criticism of legal education, it was not his only one. In speeches, such as his 2014 commencement address at William & Mary Law School, he decried the entropy of modern law-school curricula, where professors' pursuit of scattered, esoteric, sometimes eccentric research agendas translates into courses that "offer a student the chance to study whatever strikes his or her fancy — so long as there is a professor who has the same fancy."

He urged schools to turn back from the proliferation of "Law and..." courses, to reaffirm that students' degrees reflect their "sustained three-year study of law. The mastery of that subject is what turns the student into a legal professional," he emphasized. Only by returning to a core curriculum would students understand the law as "a more cohesive whole, instead of a series of separate fiefdoms." Ultimately, "it is good to be learned in the law because that is what makes you members of a profession rather than a trade."

Such were his two main lines of criticism of legal education: Law students are too often taught by "academics who have little regard for text and tradition," as he observed in a 2004 tribute to a friend, and who also have little interest in teaching American law as a coherent whole.

Ultimately, this model of legal education, established by Harvard's Christopher Columbus Langdell nearly a century and a half ago, had reached a point of exhaustion. "In the 140 or so years that have passed since Langdell came onto the scene," Scalia told alumni of the University of New Hampshire School of Law in 2013, "the practical virtue of American law schools as a device for the teaching of law has failed." American law schools are now mainly in the business of producing lawyers and judges who neither comprehend the law's fullness nor feel genuinely constrained by its particulars.

SCALIA'S ALTERNATIVE — AT FIRST GLANCE

Justice Scalia's critique of legal education is familiar; so too is the immediate motivation for that critique. He embraced originalism and textualism because he believed them to be the most reliable means of judicial self-restraint; and judicial self-restraint, in turn, he saw as necessary to ensure the citizenry's continued willingness to respect judicial independence. "[O]riginalism seems to me more compatible with the nature and purpose of a Constitution in a democratic system," he explained in "Originalism: The Lesser Evil." And after all, "A democratic society does not, by and large, need constitutional guarantees to insure that its laws will reflect 'current values.' Elections take care of that quite well."

He expanded on this argument elsewhere. In his dissent from the Court's decision in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey in 1992, for example, he warned that if the Court's "pronouncement of constitutional law rests primarily on value judgments," rather than on the mere interpretation of written legal terms,

then a free and intelligent people's attitude towards us can be expected to be (ought to be) quite different. The people know that their value judgments are quite as good as those taught in any law school — maybe better. If, indeed, the "liberties" protected by the Constitution are, as the Court says, undefined and unbounded, then the people should demonstrate, to protest that we do not implement their values instead of ours.

Textualism largely avoids that outcome, Scalia argued, because it establishes a relatively stable set of rules, departures from which will be detected by the public, or at least by the judge's brethren. "Willful judges might use textualism to achieve the ends they desire," he wrote in Reading Law, "[b]ut in a textualist culture, the distortion of the willful judge is much more transparent, and the dutiful judge is never invited to pursue the purposes and consequences that he desires."

Some critics — even some of Scalia's libertarian friends — might contest Scalia's belief that his textualist approach truly is the best means of ensuring limited, republican, constitutional government. No one, however, can contest that Scalia genuinely held this belief.

But why did Scalia support America's limited, republican, constitutional government in the first place? Here Justice Scalia's approach does reflect, at least in part, more fundamental commitments drawn from his own religious faith. And the best evidence of this might be found in a largely forgotten lecture given shortly after he was appointed to the Supreme Court. In that 1986 lecture, we find Scalia's most stirring arguments in support of both constitutional government and legal education. Those arguments put the rest of his thought in much clearer context.

TEACHING ABOUT THE LAW

Before his appointment to the Supreme Court, then-Judge Scalia committed to delivering the fourth annual Seton-Newman lecture, a short-lived series sponsored by the United States Catholic Conference. (It had previously featured Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and it would later feature Russell and Annette Kirk.) Despite the demands of his new job, he made good on his pre-Court commitment, delivering the lecture at the Catholic University of America in December 1986, just three months after joining the Court. He titled his lecture "Teaching About the Law."

The address was reported by the National Catholic News Service, and thus was mentioned in at least some Catholic diocese newspapers. But beyond the Catholic press, Scalia's lecture seems to have had very little impact: "As an unpublished college lecture," the Christian Legal Society Quarterly later remarked, "it ha[d] not reached a vast audience." And so the CLS Quarterly published Scalia's lecture nearly a year after he delivered it, in the journal's Fall 1987 issue.

Publication in the Quarterly did not save Scalia's lecture from obscurity. Today, nearly three decades later, this lecture by one of the 20th century's most significant justices has been cited by only five law-review articles, according to Westlaw. And four of those — three by the same author — were in "alternative dispute resolution" journals, citing Scalia's lecture for his limited point on the virtue of avoiding litigation. The effective disappearance of this lecture for nearly three decades was an immense loss to the American legal community. For, in that lecture, Justice Scalia traced the roots of his constitutionalism directly to the Bible's New Testament.

One should note from the outset that the religious influence asserted in this lecture is not the one of which he is usually accused. Throughout his career, critics such as Geoffrey Stone, Linda Greenhouse, and Dahlia Lithwick asserted or implied that Scalia's views on specific legal issues were dictated by his Catholicism. Scalia rebutted such accusations roundly, often citing examples of decisions (including Employment Division v. Smith) that cut against the interests of the Church. "[T]here's no such thing as...a Catholic interpretation of a text," he told the Hoover Institution's Peter Robinson in a 2009 interview. "Why, what's a Catholic interpretation of a text? The text says what it says." Or, as he remarked more categorically at a Pew Forum conference in 2002, "[T]he only one of my religious views that has anything to do with my job as a judge is the seventh commandment — thou shalt not lie. I try to observe that faithfully, but other than that I don't think any of my religious views have anything to do with how I do my job as a judge."

But that statement was too categorical: While Scalia's approach to judicial interpretation was not directly controlled by Catholicism, his 1986 Seton-Newman lecture spelled out the profound way in which his faith undergirded his view of the law more generally.

"The New Testament contains some important passages that address the attitude Christians should have towards the law," Scalia observed in the lecture. "The most significant and the best known is the passage from St. Paul's letter to the Romans." This letter is most often quoted for St. Paul's admonition against vengeance. But, as Scalia explained, the less-quoted lines that follow that discussion are "essential to the whole picture." He quoted the key lines in full, beginning with the most familiar: "Everyone must submit himself to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God. Consequently, he who rebels against the authority is rebelling against what God has instituted, and those who do so will bring judgment on themselves."

After those lines and several that followed, Scalia offered a caveat, that the passage "must be read to refer to lawful authority, although there is plenty of room to argue that some authorities are not lawful ones." Beyond that caveat, then, Scalia turned to "the central proposition that, for Christians, lawful civil authority must be obeyed not merely out of fear but, as St. Paul says, for conscience's sake."

In modern times, he said, "we have lost the perception, expressed in that passage from St. Paul, that the laws have a moral claim to our obedience." And this, Scalia noted, "is the first and most important Christian truth to be taught about the law, because it is truth greatly obscured in an age of democratic government," where civil government inspires too little confidence. "As Americans, it is particularly hard for us to have the proper Christian attitude toward lawful civil authority," because "our political tradition carries a deep strain of the notion that government is, at best, a necessary evil."

Scalia then offered his most important instruction to his Catholic University audience:

But no society, least of all a democracy, can long survive on that philosophy. It is fine to believe that good government is limited government, but it is disabling — and, I suggest, contrary to long and sound Christian teaching — to believe that all government is bad. As teachers, I hope, then, you can teach your students that those who hold high office are, in their human nature and dignity, no better than the least of those whom they govern; that government by men and women is, of necessity, an imperfect enterprise; that power tends to corrupt; that a free society must be ever vigilant against abuse of governmental authority; and that institutional checks and balances against unbridled power are essential to preserve democracy. In addition to these secular truths, I hope that you will teach that just government has a moral claim, that is, a divinely prescribed claim, to our obedience.

Near the end of his lecture, invoking Federalist No. 51's recognition that government's necessity reflects man's decidedly non-angelic nature, Scalia added a final emphatic observation: Law's importance grows in inverse proportion to the stock of republican virtue, for "[l]aw steps in, and will inevitably step in, when the virtue or prudence of the society itself is inadequate to produce the needed result....I suggest, in other words, that it is by teaching your students virtue and responsibility — much more than by teaching them the contents of their legal 'rights' — you preserve the foundations of our freedoms."

LAW AND REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT

In just those few paragraphs, one finds three distinct themes that informed Justice Scalia's constitutionalism, and his views on education, throughout his career.

First, that the law is an exercise in second-bests. In a Harvard Law Review memoriam, Chief Justice John Roberts reflected on the late Justice Scalia, beginning with Scalia's own hero, St. Thomas More. In More's Utopia, "Antonin Scalia's greatest gift — his judicial acumen — would have gone to waste," because there "the laws were few." But "[o]ur American democracy," by contrast, "is no legal Utopia. Our laws are many; they are often complex and produce stormy debate." And "[w]hen disputes arise, our citizens must look to the courts to discern and apply the rules without fear or favor."

The chief justice was right to credit Justice Scalia for executing faithfully the duties of his judicial office. But the premise of Roberts's praise was no less central to Scalia's approach: We live in a fallen world, and our need for legal constraints is inherently an exercise in second-bests. We rely on law not to achieve perfect outcomes, but to accomplish the best that we can realistically hope for.

In this respect, the title of one of Scalia's seminal essays is telling: "Originalism: The Lesser Evil." Scalia applied originalism not because it would always achieve good and just results, but rather because, in his view, it was less corrupted than the alternatives. (And, as he said to Peter Robinson in 2009, for a judge, to pursue perfection beyond the limits of law is, indeed, a "temptation.")

Scalia pressed this point often in his defenses of originalism, including a 2012 address to the Cambridge Union. Responding to a student's question of how to square notions of judicial restraint with the "sweeping" decision of Brown v. Board of Education, Scalia answered first that the Brown result was eminently defensible on originalist grounds, before adding that the "more important answer" is that "you can do wonderful stuff by letting the courts run the show, just as you can do wonderful stuff by letting a king run the show," but "you can't judge the totality of the system on the basis of whether now and then it produces a result that you like." The work of a judge, then, should not be defined by its ability to reach the "best" result in a particular case. Or, as he said more bluntly to Peter Robinson in 2009, "look, I do not propose or suggest that originalism is perfect and provides easy answers for everything. But that's not my burden; my burden is just to show that it's better than anything else."

This points to an important premise of Scalia's criticism of legal education and the common-law method. Lawyering and judging is not an exercise in dashing about in pursuit of an ideal result — equal parts Walter Payton and Solomon. Perfection is unattainable, and judges are no more angelic in nature than the men on whom they pass judgment.

But the second major theme highlighted by Scalia's 1986 remarks is that just government — even democratic government — has a moral claim to our obedience. As Justice Scalia keenly observed, we Americans are less inclined to respect, let alone venerate, the institutions of our government, because our government is a democratic one. This, as much as anything, would seem to animate the tendency of law professors, law students, lawyers, and judges to prize individual rights above democratic self-governance. But Scalia urges us to resist that instinct — or, more accurately, to temper it appropriately — with the recognition that government has a moral claim to our obedience, for the reasons explained by St. Paul.

This is a point that Scalia stressed years later, in a much more prominent essay: his reflections on the death penalty in First Things, titled "God's Justice and Ours." There he paraphrased the lengthier discussion of "Teaching About the Law," quoting St. Paul's letter (though this time the King James translation, not the New International Version), admonishing that "[y]e must needs be subject" to lawful government, "not only for wrath, but also for conscience sake." Scalia repeated the last words for emphasis: "For conscience sake."

And he added that Americans try to overcome our democratic suspicions "by preserving in our public life many visible reminders that — in the words of a Supreme Court opinion from the 1940s — 'we are a religious people, whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being.'" Such reminders, Scalia noted, include "In God we trust" on our coins; "one nation, under God" in our Pledge of Allegiance; the prayers that open our legislative sessions; and the plea that "God save the United States and this Honorable Court" at the outset of each session of the Supreme Court.

This, too, provides context for much of Scalia's criticism of legal education — particularly his conviction that the more democratic institutions of our government, not the courts, provide the legitimate source of law and the proper forum for changing those laws. Scalia did not see republican government as regrettable, let alone illegitimate. While he would not say vox populi vox Dei, he was much more content (to say the least) to let God work his mysterious ways through the imperfect vessels of democratic government, rather than commit such questions exclusively to purported high priests in the federal judiciary.

And this points to the third of Scalia's key themes highlighted by his Catholic University lecture. "[I]t is by teaching your students virtue and responsibility — much more than by teaching them the contents of their legal 'rights,'" he told the assembled educators, that "you preserve the foundations of our freedoms," lest the decline of virtue force the legal imposition of virtuous behavior.

Scalia's remarks on the importance of civic virtue are perhaps the subtlest part of "Teaching About the Law," and they are also the part most directly connected to Scalia's views in the Court's education cases. As noted above, Scalia urged that the moral and ethical content of legal education is no less important than the doctrinal content of that education. On this point, Scalia invoked Madison's Federalist No. 51. But he might have done well to also quote Federalist No. 55, where Madison stresses that, despite the non-angelic qualities of our nature, "there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence," and, crucially, that "[r]epublican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form."

Scalia's focus on the importance of civic virtue closely resembles the thought of one of his most prominent colleagues and friends dating back to his late-1970s days at the American Enterprise Institute: Walter Berns, a scholar of the framers and of republican virtue more generally. Berns's 2001 masterpiece, Making Patriots, strikes very similar notes to Scalia's "Teaching About the Law" on the subject of religion and civic virtue. Where Scalia examines chapter 13 of St. Paul's Letter to the Romans (on submitting to earthly government), Berns begins with chapter 12 (on why the people of a community must think of themselves as members of one body), before considering Tocqueville, who observed:

Religion in America takes no direct part in the government of society, but it must be regarded as the first of their political institutions; for if it does not impart a taste for freedom, it facilitates the use of it....I do not know whether all Americans have a sincere faith in their religion — for who can search the human heart? — but I am certain that they hold it to be indispensable to the maintenance of republican institutions.

While I have not found an example of Scalia going so far as to quote the same passage from Tocqueville (or any example of Scalia quoting Tocqueville, for that matter), Scalia's and Berns's common reference to St. Paul's Letter to the Romans is interesting.

In any event, one can draw a direct line between this aspect of Scalia's thought and his opinions in the Supreme Court's education cases. Time and again, Scalia criticized efforts by the courts and others to strip the fostering of virtue — civic or otherwise — from schools. In Lee v. Weisman, for example, Scalia goes out of his way in dissent to "add, moreover, that maintaining respect for the religious observances of others is a fundamental civic virtue that government (including the public schools) can and should cultivate — so that even if it were the case that the displaying of such respect might be mistaken for taking part in the [graduation] prayer, I would deny that the dissenter's interest in avoiding even the false appearance of participation constitutionally trumps the government's interest in fostering respect for religion generally."

In Lamb's Chapel v. Center Moriches Union Free School District, meanwhile, Scalia closed his concurrence by rejecting the New York attorney general's argument that religious advocacy "serves the community only in the eyes of its adherents, and yields a benefit only to those who already believe." Nonsense, Scalia replied: "That was not the view of those who adopted our Constitution, who believed that the public virtues inculcated by religion are a public good." He quoted the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which announced, "Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged."

Perhaps the most famous instance is his emphatic dissent in the VMI case, United States v. Virginia, which he closed with an extended quotation from VMI's "The Code of a Gentleman." After quoting the code's maxims, Scalia observed, "I do not know whether the men of VMI lived by this Code; perhaps not. But it is powerfully impressive that a public institution of higher education still in existence sought to have them do so. I do not think any of us, women included, will be better off for its destruction."

In these cases, and surely elsewhere, Scalia's view of constitutional rights in the educational context took due consideration of the need for the inculcation of virtue, not just for the sake of individual students, but for the sake of our republican government in general. Like Mary Ann Glendon in Rights Talk, Scalia saw the trends in education, and in modern constitutional law, that promoted (in Glendon's words) "relentless individualism" that, "[i]n its neglect of civil society...undermines the principal seedbeds of civic and personal virtue" — trends that, in so doing, undermine our capacity for limited, republican government.

This was a point that Scalia pressed in one of his last public speeches: a June 2015 commencement address at Maryland's Stone Ridge School of the Sacred Heart, where his granddaughter was among the graduates. Challenging the platitude that "we are the greatest [nation] because we are the freest," Scalia argued that "precisely the opposite is true: we are the freest because we have those qualities that make us the greatest. For freedom is a luxury that can be afforded only by the good society. When civic virtue diminishes, freedom will inevitably diminish as well."

In making this point at Stone Ridge's commencement, Justice Scalia came full circle, echoing precisely the same point that he had made in the Seton-Newman lecture at the very outset of his career on the Court. Indeed, he used almost the exact words that he had used in his 1986 lecture. Paraphrasing Lord Acton (as he did in 1986), Scalia told the graduates, "that society is the freest which is the most responsible. The reason is quite simple and quite inexorable: Legal constraint, the opposite of freedom, is in most of its manifestations a cure for irresponsibility." Scalia then pointed the students (as he did in 1986) to Madison's discussion of government as necessary for non-angelic societies.

And then Scalia added words drawn virtually verbatim from his 1986 lecture: "Law steps in, and will inevitably step in, when the virtue and prudence of the society itself is inadequate to produce the needed result."

THE PROFESSION OF LAW

All of the foregoing helps to explain Justice Scalia's view of legal education, quoted above, as "preparing men and women not for a trade but for a profession — the profession of law."

We so often hear the work of lawyers and judges described in terms of craft — Justice David Souter employed the term, as did Chief Justice William Rehnquist. A half-century ago, Judge Learned Hand closed his famous Holmes Lectures with a tribute to his own teachers: "From them I learned that it is as craftsmen that we get our satisfactions and our pay." While such descriptions of judicial "craft" are no doubt well-intentioned, they unintentionally reflect a risk of lawyering and judging with too myopic a vision of the task at hand. Excessive focus on the virtues of "craftsmanship" risks distracting us from the concomitant vices. As Richard Sennett put it in his 2008 book, The Craftsman, "[t]he craftsman's desire for quality poses a motivational danger: the obsession with getting things perfectly right may deform the work itself." (Judge Hand himself personified such a danger: The 1958 lectures in which he offered his ode to "craftsmanship" were the same ones in which he infamously condemned Brown v. Board of Education.)

That is the risk that Justice Scalia warned against in his 2014 commencement address at William & Mary. In urging law schools to teach students not a "trade" in the law but a "profession," he highlights a crucial distinction. A trade, or a craft, is undertaken just with an aim toward technical perfection. A profession, by contrast, is informed and limited by larger considerations — our larger civic, ethical, and moral responsibilities. Thus Scalia's goal of lawyers becoming not just skilled in particular subjects, but "learned in the law": It is only by learning the law broadly, putting each specific subject in the context of the rest, and putting the law as a whole in the context of republican government (and, ideally, under God), that lawyers can fully appreciate the limits of the law.

This is one of the important lessons that Justice Scalia seemed to draw from his hero, St. Thomas More, as described in Scalia's occasional remarks on "The Two Thomases," Thomas Jefferson and St. Thomas More. By Scalia's description, Jefferson was a "lawyer who was something of a universal man." In Jefferson's case, Scalia meant a man unashamed even to blue-pencil the Bible in order to make it (in Scalia's words) "a Gospel fit for the Age of Reason." Jefferson, so focused on what he saw to be rational escape from superstition, truncated his intellectual field of vision to preclude anything smacking of the supernatural.

The other Thomas, St. Thomas More, was in his own time "one of the great men of his age: lawyer, scholar, humanist, philosopher, statesman — a towering figure not just in his own country of England but throughout Renaissance Europe," Scalia added. But unlike Jefferson, More recognized the limits of his lawyer's and intellectual's tools, even when so many others did not — indeed, even when his own wife did not. Quoting Robert Bolt's A Man for All Seasons, Scalia tells the story of More's decision to resign his chancellorship. When More asks his wife, Alice, to help him remove the chain of office, "She says: 'Sun and moon, Master More, you're taken for a wise man! Is this wisdom — to betray your ability, abandon practice, forget your station and your duty to your kin and behave like a printed book!'" Later, More's friend tells him, "You're behaving like a fool. You're behaving like a crank. You're not behaving like a gentleman."

"But of course," Scalia observes, "More was not seeing with the eyes of men, but with the eyes of faith." (And thus, Scalia observes in this talk and others, More exemplified St. Paul's injunction that all Christians must allow themselves to be seen as "fools for Christ's sake," and thus "to suffer the contempt of the sophisticated world for these seeming failings of ours.")

To state the point more broadly, if less religiously, More was recognizing the limits of lawyerly craft. He recognized that his work as a lawyer under the king was itself circumscribed by larger commitments, commitments that cannot be found within the four corners of legal doctrine, but which are no less important to the ultimate work of lawyers and judges, rightly understood.

And thus, while law schools need not become religious institutions (though it wouldn't hurt if the religious ones stayed so), they fail their students when they neglect to inculcate virtues necessary to sustain our republican government.

As noted above, Justice Scalia often expressed his views of originalism, of republican government, and of legal education without reference to his Catholic faith. Indeed, the fact that Scalia's religious faith informed his constitutional and political principles does not mean that those principles can only be informed by religious faith. Still, in trying to understand Scalia's own thought, his forgotten "Teaching About the Law" essay is indispensable for placing his thought in its proper context. While his Catholic faith did not dictate his interpretations of laws, it did undergird his approach in general.

On that point, it is impossible to improve upon the words of Fr. Paul Scalia, in the homily at his father's funeral service:

God blessed Dad, as is well known, with a love for his country. He knew well what a close-run thing the founding of our nation was. And he saw in that founding, as did the founders themselves, a blessing. A blessing quickly lost when faith is banned from the public square, or when we refuse to bring it there. So he understood that there is no conflict between loving God and loving one's country, between one's faith and one's public service. Dad understood that the deeper he went in his Catholic faith, the better a citizen and a public servant he became. God blessed him with a desire to be the country's good servant, because he was God's first.

To that same end, Justice Scalia resisted attempts by judges and others to impair today's students from coming to understand these same truths. He implored legal educators to truly do justice to the task at hand.