America in the Red

In his State of the Union address on January 27, President Obama asked the Congress to commit with him to "invest in our people without leaving them a mountain of debt." Four days later, he released his budget — which showed that, unless we change course, a huge mountain of debt is exactly what we can expect.

Everyone understands that the federal government's finances are a mess, and that policymakers have failed to take the problem seriously. "Paying for what you spend is basic common sense," Obama quipped last June. "Perhaps that's why, here in Washington, it's been so elusive." Unfortunately, this familiar punch line is no longer a laughing matter: The explosion of borrowing in the past two years, and the prospect of unrelenting deficits in the next decade and beyond, portend the deterioration of America's economic strength.

Because our budget woes are so complicated and immense, they cannot be resolved with one silver bullet. Our leaders will need to embrace a range of unpopular options — including spending reductions and tax increases — in order to protect America's prosperity and vitality. But not all of these options are created equal. And as policymakers begin to address our fiscal challenges, they will need to prioritize key principles and goals for responsibly reining in our budget, while also remaining open to policy proposals that require political compromise.

To understand what those proposals might look like, and what principles should animate them, we must first appreciate the nature of the challenge we face. It is, unfortunately, both urgent and daunting.

DARK BUDGET PROSPECTS

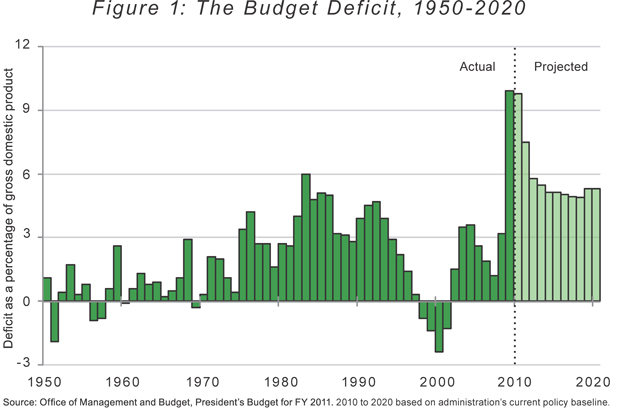

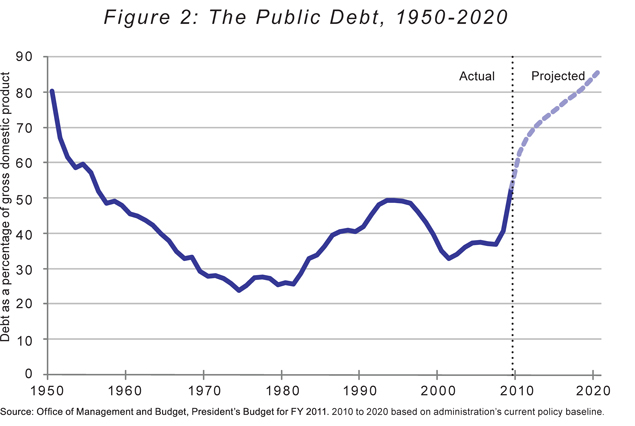

America is digging itself into a deep fiscal hole. In 2009, the federal government spent $3.5 trillion, but took in only $2.1 trillion in revenue — thus spending $1.67 for every dollar it collected. The resulting $1.4 trillion deficit was equivalent to 10% of the nation's economic output, the highest percentage since the end of World War II. America's publicly held debt now totals $7.5 trillion, about 53% of gross domestic product — the highest it has been in more than 50 years.

These figures are alarming, but they pale in comparison to budget projections for the years ahead. Recent numbers from the Obama administration show that if current policies were to remain in place, deficits would average more than $1 trillion annually for the next ten years, amounting to more than 5% of GDP. Those deficits would then ensure that the national debt would grow much faster than the economy: By 2020, the United States would owe more than $20 trillion, the equivalent of about 85% of GDP. At that point, interest payments alone would consume about $900 billion a year — almost five times as much as they did in 2009.

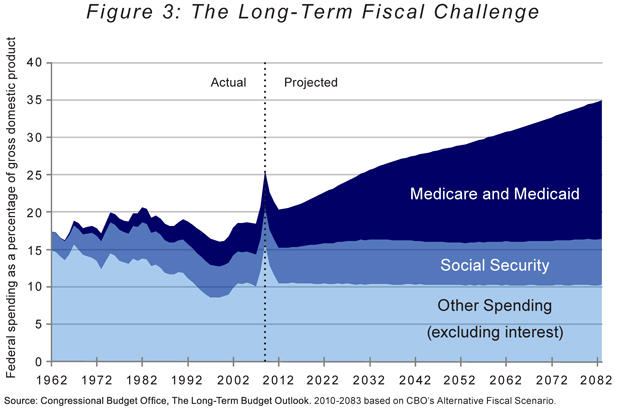

The outlook grows even more bleak when we account for the ongoing retirement of the Baby Boomers and further increases in public spending on health care. According to the Congressional Budget Office, spending on Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security is on track to grow from about 10% of GDP today to about 16% in 2035. At the same time, the aging of the population means that the labor force — and, therefore, tax revenues — will grow more slowly in the future. The twin pressures of increased entitlement spending and slowing revenue growth mean that the debt will skyrocket — to roughly 200% of GDP in 2035, under one CBO scenario — unless there are dramatic cutbacks in all other government activities or an equally dramatic increase in taxes.

Our current staggering deficits are therefore just a small part of a much larger fiscal dilemma. The financial crisis has added several trillion dollars to America's indebtedness, but our structural deficits — which will continue even after the economy recovers — are on track to add tens of trillions of dollars more in the coming decades.

Budget-watchers once spoke of these looming challenges as a distant, long-term threat — something quite separate from the more pressing budget challenges that we might face over, say, the next ten years. That is no longer true. Today, those big "long-term" troubles are our urgent problems; they start to materialize within the usual ten-year budget window. Spending on Social Security benefits, for instance, is projected to exceed Social Security tax revenues in 2010 and 2011, and the Medicare trust fund is projected to run out of money in 2017. We now live in a world in which financial markets speculate about the odds of the U.S. government's defaulting, and in which major foreign creditors express concern about our ability to pay our debts.

It was not so long ago that such scenarios seemed impossible. But the decades of punting on our long-term budgetary challenges have finally caught up with us. As the Great Recession begins to abate, we need to move quickly to avert our looming fiscal crisis.

WHY DEFICITS AND DEBT MATTER

Before we can hope to make a dent in our deficits and debt, there must be broad agreement among the public and the governing class that we even need to. There are still some commentators on both the right and the left who continue to insist that deficits and debt do not matter much. It is important to understand why they are mistaken.

Running deficits can certainly be appropriate — and even beneficial — at times of particular stress, such as wars and recessions. But in the long run, persistent large deficits and growing debts undermine our nation's prosperity.

First, once our economy is back on its feet, prolonged deficits and mounting debt will inevitably undermine economic growth. Americans simply do not save enough both to lend the government everything it needs to finance persistent deficits and to continue investing in the growth of the private sector. Future government borrowing will therefore require either more borrowing from abroad or significantly less domestic investment. If we reduce our domestic investment — building fewer factories, cutting back on research and development, and generating fewer innovations — our nation's future earnings prospects will dim, and our future living standards will suffer. And while borrowing more from foreign lenders enables us to afford more investment today, that money (plus substantial interest) will eventually have to be repaid. As a result, more of our future income will have to be sent overseas — and again, our living standards will decline. Sometimes economics can be painfully simple: The more money we borrow now, the less we will have in the future.

Second, prolonged deficits may fuel concerns about inflation. Typically, governments that need to get deficits under control must turn to some combination of tax increases and spending cuts. Both policy measures are easily grasped by the people they affect — and are therefore generally unpopular. So governments are often tempted to follow an easier path: printing new money to cover deficits and reduce the real value of debt. By printing money, governments can avoid the unpleasantness of raising taxes, cutting spending, or borrowing from demanding investors; the subsequent inflation, however, is simply a hidden tax.

At this point, there is no reason to believe that the Federal Reserve would agree to any large-scale move that would increase inflation. The Fed has taken extraordinary steps in combating the financial crisis — including the purchase of long-term Treasury bonds — but it remains committed to undoing these steps once economic conditions permit. Nevertheless, the experience of other nations makes investors wary. And if deficits continue on their current path, those lenders will eventually demand an inflation premium on their investments in America, just in case. The cost of borrowing would increase — making it more expensive for families to buy homes, for companies to invest in new equipment, and for the government to finance its debts. Economic growth would thus slow just as rising interest burdens worsened our fiscal situation. And the dollar, still the world's reserve currency, would come under even greater pressure.

Third, as the share of a nation's debt held by foreign lenders increases, that nation relies ever more upon the goodwill of its creditors. During World War II, individual Americans purchased most of the debt needed to finance the war effort. As a nation, we thus owed the money to ourselves. Today, however, much of our debt is held abroad, and we rely heavily on overseas investors to purchase new debt issues. Consequently, domestic fiscal policy is now an important point of contention in our diplomatic relationships — particularly with countries like China and Japan, which have been the largest buyers of Treasury securities. These countries now believe that their willingness to finance our debt gives them leverage in negotiations about other issues, ranging from nuclear proliferation to human rights. Such leverage cannot be beneficial for America's competitive or strategic interests.

Fourth, and closely related, the growing debt exposes America to greater "rollover" risk. Over the past two years, the United States has become increasingly reliant on short-term debt. That reliance has made sense during a period of exceptionally low interest rates; indeed, the low rates allowed us to spend less on interest in 2009 than in 2008, despite the dramatic expansion of our debt. Over the long run, however, heavy dependence on short-term debt amplifies the risk that our creditors may one day be less willing to invest in Treasury securities. In 2010, for example, the federal government will need to sell more than $1 trillion in bonds to finance the annual deficit; it will need to sell another $3 trillion in bonds to refinance maturing issues. The Treasury appears capable of placing this enormous amount of debt — for now. But the constant pressure to refinance only adds to our fiscal risks.

Fifth, rising debts limit flexibility. In principle, the United States should maintain a rainy-day fund as insurance against wars, economic crises, or other sudden spending needs. In practice, that rainy-day fund has been our ability to borrow at will. But that ability has limits, and we have already tested them in our response to the financial and economic crises. The further we fall into debt, the less of a cushion we have to respond to future calamities.

Sixth, deficits have an unfortunate tendency to feed on themselves. Consider that if the government were to borrow $1 trillion this year, it would have to borrow another $40 billion next year to cover interest payments (assuming a typical interest rate of 4%). If it did not pay off the debts at that point, it would then have to borrow another $42 billion the following year (because of compounding interest), and growing amounts thereafter. Moreover, that power of compound interest can be magnified if persistent deficits lead to higher interest rates — through a combination of concerns about inflation and potential default, and the potential for increasing government debt to drive up market interest rates. Deficits financed at 4% today can thus lead to more deficits, financed at higher rates, in the future.

Finally, deficits present fundamental problems of intergenerational fairness. If we borrow in order to make investments — e.g., to build infrastructure, advance medical research, or make the world safer — future generations receive some benefit in exchange for the debt they must repay. Indeed, depending on the success of these efforts, future generations may well receive enough benefits to more than offset the costs of paying down the debt that we bequeath to them. But if we borrow merely to finance our own consumption, there are no benefits for future generations. Given the nature of much of today's spending — predominantly consumption, not investment — we must acknowledge that our borrowing places an unfair imposition on future generations of Americans, who will sacrifice the fruits of their labor to pay off a debt they had no role in incurring.

SETTING GOALS

For all of these reasons, it is essential that the United States acknowledge the irresponsibility of our budgeting behavior, show some self-discipline, and move swiftly to avoid fiscal catastrophe. In order to do so, however, we must have a clear understanding of what the ultimate goals of our fiscal policy should be.

Defining these goals requires making some fundamental decisions about the size and role of government. Some Americans prefer a large, active government that provides a broad range of services and redistributes income among individuals and families in order to diminish disparities in economic outcomes. Other Americans prefer a smaller, limited government that provides essential public services — defense, a legal system, and a basic social safety net — but leaves most other decisions to individuals, families, and the private sector. A smaller government makes the task of keeping spending — and therefore deficits — under control somewhat easier. But if we choose a larger government, Americans must recognize that we will have to pay for it through higher taxes. Unbridled borrowing is simply not a viable long-term option.

Whatever government we choose, any plausible budget-policy goal must, at a minimum, seek to prevent the federal debt from persistently growing faster than the economy. Just as a family cannot support debts that grow faster than its income, a government cannot support debts that grow faster than its tax base. As a result, there is no way the budget can be brought under control unless we can curb the accelerating growth of debt. In technical terms, our first goal should be to stop the debt-to-GDP ratio from rising.

Achieving this modest goal does not require anything close to a balanced budget. Preventing the debt-to-GDP ratio from increasing requires only that economic growth in nominal terms (i.e., reflecting both real growth and inflation) at least match the rate at which deficits add to the debt. For instance, if the debt-to-GDP ratio is 60%, and the economy is growing at 5% in nominal terms (a typical pace in decades), the government can run a deficit of 3% of GDP without increasing the debt-to-GDP ratio. But if the economy grows more slowly — as is likely in the coming years — the sustainable deficit level will be correspondingly lower.

Unfortunately, our nation is on course to miss even that relatively easy budget goal. As the Obama administration showed in its recent projections, current policies would cause the debt to grow faster than the economy in every year from 2010 through 2020. As a result, the debt-to-GDP ratio would increase from about 41% in 2008, before the worst of the financial crisis, to more than 85% in 2020.

In a sane world, such a high debt burden would be unacceptable. Congress must therefore work with President Obama to put our budget on a trajectory in which the proportion of debt to GDP flattens out, and eventually declines, rather than rising indefinitely.

What debt-to-GDP ratio should they aim for? Economic research demonstrates that countries face greater financial burdens as their debt-to-GDP ratios increase, but there is no hard and fast threshold between manageable and problematic debt levels. Choosing targets is thus as much a matter of political art as it is economic science.

Any reasonable proposal should combine three elements: a near-term cap on how high the debt will be allowed to grow, as well as medium- and long-term goals for bringing the debt-to-GDP ratio down to manageable levels.

Given the aftershocks of the financial crisis and America's ongoing economic weakness, large deficits and growing debt are inevitable and likely appropriate during the next fiscal year (or two). Serious deficit reduction should therefore begin in 2012, with a near-term goal of ensuring that the debt-to-GDP ratio does not rise higher than the levels projected for fiscal years 2012 and 2013. Based on the president's recent budget submission, that would imply a near-term goal of limiting the growing debt to no more than 70 to 72% of GDP.

A strictly limited 70% debt-to-GDP ratio is clearly preferable to one that grows without bound, but it is still too high for comfort. Among other things, it would imply that ongoing interest payments would be a substantial burden on the budget — consuming about 3% of GDP a year. So setting this 70% cap can only be a starting point; deficit reduction must continue so that the debt-to-GDP ratio is significantly lowered by the end of the decade.

One plausible mid-term target, recently endorsed by the Pew-Peterson Commission on Budget Reform, would be to lower the debt-to-GDP ratio to 60% by 2018 (though given the most recent budget, 2020 may be a more reasonable goal). As the Commission notes, the 60% benchmark has often been used by international organizations to determine whether nations have their finances under control: The Growth and Stability Pact of the European Union, for example, stipulates that member nations should keep their public debts below 60% of GDP. Many European nations have loosened this stricture during the recession, but intend to re-apply it once their economies strengthen.

Getting the debt-to-GDP ratio down to 60% over the next ten years will require some tough decisions by our elected leaders. For example, total deficits from 2012 through 2020 would have to be reduced by about $6.4 trillion, or about 3.5% of GDP. Such reductions would be almost three times as large as those specifically proposed by the president in his recent budget. (The president has also proposed a fiscal commission to achieve greater deficit reductions.)

But even this 60% figure is too high over the long term. Before the financial crisis, America's debt-to-GDP ratio had averaged about 40% over more than half a century. As we look beyond the next decade, we should aspire to return to that level.

THE MYTH OF SINGLE SOLUTIONS

Once we establish a target, we will need to decide how to reach it. And as with almost any large, complex problem, there is a natural desire to resolve our budget crisis with just a single solution. Some observers look at the numbers and conclude that the solution is obvious: raise taxes to pay for the additional spending. Others look at the same figures and conclude just the opposite: cut spending so we do not need to move beyond historical levels of taxation. And most observers cling to the hope that growth might set us free, boosting revenues so much that we will not have to face any hard choices. Unfortunately, none of these single solutions will work.

When it comes to economic growth, we should start with the obvious: Hope is not a strategy. History suggests that economies are often slow to recover from severe financial crises, and so we should be cautious in our expectations. America's economy may well grow faster than budget analysts expect in the coming years, but as recent experience demonstrates, it may also fall far short.

Moreover, even if future growth turns out to be surprisingly strong, it will not be enough to cure our fiscal ills. Suppose, for example, that the economy grew at an average real rate of 3.8% per year over the next ten years — fully 0.5 percentage points higher than the Obama administration's most recent forecast of 3.3%. Such strong growth would be a welcome surprise for both the economy — which hasn't grown at such a rate over a decade since the late 1960s and early '70s — and federal coffers, which would receive an unexpected surge of tax revenues. Were such growth to materialize, it would, by a rough estimate, reduce the ten-year deficit by about $1.5 trillion. That is real money, and a good reason why promoting growth should be a key part of our deficit-reduction strategy. But it still falls far short of the $10 trillion in cumulative deficits that the nation is projected to run over this same ten-year period.

Since higher growth alone cannot in fact set us free (and may not even materialize), some observers have focused on tax increases as the solution to our fiscal woes. But the American people are unlikely to accept tax increases large enough to eliminate our growing fiscal-imbalances. Consider just one (plausible) scenario sketched out by CBO: Assuming that tax revenues over the next 25 years average about 20% of GDP, closing the fiscal gap in that same time period would require cuts in spending amounting to more than 5% of GDP. Closing the gap without any spending adjustment, and relying on taxes alone, would thus require tax revenues to exceed 25% of GDP. This amount is significantly higher — 40% higher, to be exact — than the roughly 18% average of recent decades. Such a dramatic increase would surely infuriate the taxpaying — and voting — public, and therefore seems highly improbable.

Improbable turns to impossible if policymakers seek to address our fiscal imbalance solely through tax hikes on individuals and families with high incomes. President Obama has backed himself into an unsustainable position with his campaign pledge not to raise taxes on Americans who earn less than $250,000 a year. The difficulty of upholding that pledge has already been illuminated by the debate over how to pay for an expanded federal role in health insurance. Once we turn to our ongoing fiscal problems, it will become obvious that high-income Americans simply do not make enough money to bear all the costs of fixing the federal budget. Consider some recent analysis by the Brookings-Urban Tax Policy Center's Rosanne Altshuler, Katherine Lim, and Roberton Williams, whose calculations suggest that the top two marginal tax rates would have to be increased to at least 70% to bring the deficit under control through tax increases on high earners alone. And even that measure seems unlikely to work — since, as they note, these calculations do not take into account the negative economic consequences of such high tax rates.

Finally, there are those who propose fixing the budget exclusively through cuts in spending. This approach has superficial arithmetic appeal, since recent decades have demonstrated that we can afford federal spending of, say, 20% of GDP supported by tax revenues of about 18% of GDP. If we could just cut spending enough — or, more precisely, cut the growth of spending enough — we should be able to address our nation's fiscal woes without raising taxes.

The problem with this view is that it, like the taxes-only view, ignores both economic and political reality. Our nation has made a commitment — one that the administration and congressional leaders hope to expand in the years ahead — to finance a large portion of Americans' health care through the federal government. That spending is already growing rapidly as health-care costs rise and the ranks of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries expand. At the same time, we are committed to providing Social Security benefits to growing numbers of retirees, their survivors, and the disabled. These entitlement programs are responsible for the great bulk of the projected increases in federal spending over the coming decades. Given these trends, it is inconceivable that lawmakers will be capable of solving — or, for that matter, willing to solve — our budget challenges just by slashing popular spending programs.

The bottom line, then, is clear: No one solution — not economic growth, not tax increases, and not spending reductions — can get us to our goal. To put ourselves on a sustainable fiscal trajectory, we will need to use all the measures at our disposal.

THE ROAD TO DEFICIT REDUCTION

Determining precisely the right mix of policy fixes is easier said than done. But as policymakers try to feel their way to a solution, there are some basic, useful principles about budgeting and deficit reduction they can look to as a guide.

They can begin with a seemingly self-evident principle: Set firm budget goals. The best way to get results is to set out clear benchmarks for where you want to end up, and put mechanisms in place to ensure you will be held accountable for meeting them. One approach, discussed earlier, would be to set out a near-term limit for the debt-to-GDP ratio (e.g., 70%), a medium-term target (e.g., 60%), and a longer-term goal (e.g., 40%). Another approach would be to establish fixed deficit targets that have a similar effect — stopping the runaway growth of debt and eventually bringing debt levels back down to a more normal range. Whatever the specifics, the key is establishing transparent numerical goals that can then be used to guide budget decisions, to communicate with the public, to build confidence within the financial markets, and to hold our leaders accountable.

Second, policymakers should keep all of their options open. To put the budget on sound footing, they will need to combine proposals to cut spending, increase revenues, and, where possible, boost growth. And as they begin to discuss policies for achieving each of these goals, it is important that policymakers not constrain themselves unnecessarily by ruling out some of the more politically difficult fixes. If lawmakers choose to increase taxes, they should not imagine they can shield the middle class from the effects of those increases. And although health-care spending has become the largest part of the federal budget, it cannot be the only area of federal spending to face reductions. Every program should be on the table, including those as politically sensitive as agricultural subsidies, Social Security, and defense.

Such inclusiveness and flexibility are needed both to achieve our ultimate budget aims and to build political consensus for pro posed reforms. International Monetary Fund director Jens Henriksson put it well in his reflections on Sweden's recovery from its fiscal crisis in the 1990s: "As a politician you can never explain why you need to cut pensions alone. But if, at the same time, you cut child benefits and unemployment insurance and raise income tax[es] for the richest, you are on safe ground. The idea is to not single out the losers." Safe ground may be an exaggeration, but there is no doubt that spreading the pain can help overcome political obstacles.

Third , any eventual solution must put spending cuts front and center. To be more precise, policymakers should give extra attention to reducing the growth rate of spending.

There are two reasons that spending deserves particular emphasis. The first is a matter of baseline trajectories. Driven by an aging population and rising health-care costs, the government's biggest long-term financial obligations — Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security — grow faster than the economy each year. For that reason alone, these spending programs deserve special attention in any effort to get our fiscal house in order. Without serious reform of Medicare and Medicaid especially, we have virtually no hope of controlling future deficits.

Furthermore, experience suggests that spending reductions tend to be more successful than tax increases in achieving sustained budget improvements. That conclusion has been upheld by a number of studies, including recent work by Harvard economists Alberto Alesina and Silvia Ardagna. Their study — which looked at attempts at fiscal consolidation in developed economies from 1970 to 2007 — found that fiscal adjustments based on spending reductions were much more likely to result in sustained declines in deficits and debt-to-GDP ratios than were efforts based on tax increases.

Fourth, policymakers should recognize that different spending challenges require different approaches. For Social Security, the key issue is political will. The challenges posed by Social Security are well understood: As the Baby Boomers retire, benefit payments will increase faster than the revenues that support the program. As a result, the program's surpluses will soon be replaced by persistent, growing deficits. Analysts have proposed several ways to bring Social Security's spending into line with its revenues, and there is a well-defined set of policy dials that can be adjusted — such as the age at which benefits begin, the progressivity of the payment schedule, the fraction of wages and salaries subject to the Social Security tax, and so on. Different analysts reach different conclusions about exactly how to adjust these dials, but whatever their preferences, the basic story is the same: Social Security's finances can in fact be fixed, once political leaders are ready to make hard decisions.

Health care is another matter entirely. While Social Security provides benefits in cash, Medicare and Medicaid pay for a service — the cost of which is not wholly within the government's control and is also growing at an explosive rate. Despite some rhetoric about solving the problem once and for all, the reality is that no one really knows what to do to rein in federal health spending. There are lots of ideas — strengthening consumer incentives, changing provider incentives, investing in prevention, squeezing doctors and hospitals, or moving to a single-payer system — but no one can be sure how much any of these measures would actually "bend the cost curve" over the long run. Policymakers should therefore approach health spending as a research-and-development challenge, not as a one-time matter of setting specific policy dials. Experimentation, learning, and reform will be essential as we pursue policies to reduce the growth of health-care costs. Budget-setters can take some immediate steps to reduce the growth of health spending (e.g., by limiting Medicare payment rates), but this is a dilemma that will require ongoing attention. The challenge of health-care costs is far more difficult than that of Social Security.

Fifth, policymakers must understand that while some tax increases will almost certainly be required, not all taxes are created equal — and that which form the tax hikes take will make a big difference to our future prosperity.

Taxes on income, for example, are usually worse for the economy than taxes on consumption. That is why one finds a rising chorus of economists recommending the introduction of a value-added tax, rather than higher income taxes, if our nation decides it wants to support substantially higher government spending. High tax rates similarly tend to be worse for the economy than low rates — which is why economists usually favor reforms that eliminate special exemptions and deductions, thus broadening the tax base and allowing for lower rates. Finally, it is preferable to levy taxes on behaviors we want to discourage rather than on those that are necessary for economic growth. Where appropriate, taxes on pollution, for instance, should be preferred over taxes on working, saving, or investing.

This approach to taxes is derived from a broader — and crucial — imperative that policymakers should heed as they seek to improve our fiscal health: Promote growth, or at least minimize the harm to it. As lawmakers consider changes to spending and tax policies, they must always consider carefully the effects their proposals will have on economic expansion.

For instance, policymakers should not always assume that a larger government will necessarily translate into weaker economic performance. A few years ago, Peter Lindert — an economist at the University of California, Davis — looked across countries and across time in an effort to answer the question, "Is the welfare state a free lunch?" He found that countries with high levels of government spending did not perform any worse, economically speaking, than countries with low levels of government spending. The result was surprising, given the usual intuition that a larger government would levy higher taxes and engage in more income redistribution — both of which would undermine economic growth.

Lindert found that the reason for this apparent paradox is that countries with large welfare states try to minimize the extent to which government actions undermine the economy. Thus, high-budget nations tend to adopt more efficient tax systems — with flatter rates and greater reliance on consumption taxes — than do countries with lower budgets. High-budget countries also adopt more efficient benefits systems — taking care, for example, to minimize the degree to which subsidy programs discourage beneficiaries from working.

Of course, the United States should work to reduce the economic inefficiencies in our current policies regardless of whatever else we decide. But such efforts will be even more important if America chooses — either explicitly or, more likely, implicitly — to become a higher-budget country. Our existing tax system is notoriously inefficient and will not scale well to higher revenue demands. If policymakers decide they want to boost revenues, they will need to embrace a more efficient tax system — perhaps including value-added taxes — even if they are perceived as less progressive. Similarly, as spending programs expand, policymakers should focus on ways to reduce the anti-work incentives implicit in such programs. (The incentive for early retirement created by the structure of Social Security benefits would be a good place to start.) These kinds of reforms would make sense regardless of the direction of federal spending policy — so leaders across the political spectrum should be able to agree on many of them.

Finally, our leaders should obey the first law of holes: When you are in one, stop digging. Unfortunately, the current climate in Washington encourages the exact opposite: Dig as fast as you can while there's still time.

That impulse is evident in many recent policy initiatives. Lobbyists are already arguing that various temporary provisions in the 2009 stimulus bill should be made permanent. While the congressional committees with oversight of education spending have found a way to eliminate $80 billion from the federal student-loan program, they plan to use most of it to expand other spending, rather than to reduce the deficit. The committees in charge of energy and environmental policy are considering proposals that would create almost $1 trillion worth of carbon allowances over the next ten years — only to give away or spend 99% of that money. And then there is the Democrats' health-care initiative, which would make a series of cuts to the budget only to use the savings to expand the federal government's role in financing health care.

Proponents can muster arguments for each of these reforms individually. In the aggregate, however, these government expansions are using up some of the more promising options we have for putting our budget on a more sustainable path — and so leaving us with less to work with when our budget shortfalls become an economic emergency.

IT CAN BE DONE

Daunting as America's fiscal challenges are, we should not lose hope. Indeed, Americans can take comfort from the fact that we are hardly the first nation to face such enormous fiscal problems. Although some countries have suffered prolonged periods of stagnant growth and rising debt — Japan being the most notable example — many have found their way back from the brink.

Consider Sweden, which found itself in dire fiscal straits after its financial crisis in the early 1990s. The country's deficit reached 11.6% of GDP in 1993, and budget forecasters were projecting that its debt-to-GDP ratio would increase to more than 125% by 2000. But Sweden embarked on an ambitious course of fiscal consolidation, cutting spending and increasing tax revenues. Coupled with a vibrant economy, these steps helped Sweden turn its enormous budget deficits into surpluses. And in 2000, the country's debt-to-GDP ratio was down to almost 50%.

Sweden's success is striking, but not unique. Several European nations, including Finland and Ireland, have achieved comparable turnarounds in recent decades. Moreover, the United States itself has twice managed substantial reductions in its debt-to-GDP ratio. Following World War II, the United States lowered its ratio from 108% to 52% over just ten years (though under much more favorable economic conditions than we face today). And we reduced our debt-to-GDP ratio from almost 50% to below 35% during the 1990s.

Fiscal consolidation can be accomplished. The question is whether we can find the will. Most of our political leaders understand the challenges we face, but as yet only a few seem ready to address them. Instead, budget concerns continue to be trampled by efforts to expand the reach of government and satisfy various special interests.

Some try to duck the budget issue by saying that we shouldn't tighten our belts when the economy is so weak. This is true in a limited sense: We do not want major tax increases or spending reductions in 2010 or 2011. But we can — and must — hurry to put our nation on a more sustainable path, so that desperately needed policy reforms can take effect as soon as economic conditions allow. A move to shore up our finances might even help to improve those conditions. World financial markets would certainly welcome signs that the United States recognizes its budgetary challenges and is willing to take hard steps to address them. And families and businesses would appreciate the advance warning about future changes in their taxes and benefits.

The most important reason to overcome political inertia, however, is that regaining fiscal stability is a time-consuming endeavor. Even the easier and more promising proposals — such as progressive indexing of Social Security benefits — would take many years to begin yielding major budget savings. And every day we delay, disaster rushes at us faster — because regardless of the naysayers' claims, runaway deficits and debt do matter. If we fail to address them, we will sacrifice future economic growth, sabotage our own global position, and bequeath to our children an America less prosperous and secure than the one we inherited. We must act now to avert our looming fiscal crisis. America's strategic and economic interests — not to mention plain old common sense — demand it.