Against Casino Finance

Unlike the 1929 stock-market crash, the financial crisis of 2008 did not throw the world into an economic depression. It did not lead to bread lines, riots, or radical political movements. But the recent crisis has had an unfortunate ideological effect: It has helped to undermine the legitimacy of democratic capitalism. It has breathed new life into left-wing economic critiques that question the premises underlying our economic system — free markets, relatively light regulation, and limited government involvement in the economy.

Unfortunately, this ideological fallout from the crisis has played into the hands of those who would significantly restrict our system of free enterprise. Politically, this has worked to the advantage of the Obama administration and its Democratic allies in Congress: The Democratic Party is seen as the party of regulation, and, as recent elections have shown, it is easy to drum up popular support by pledging to crack down on Wall Street.

Democrats in Washington made good on their pledge with the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. During the presidential election, they repeatedly pointed to Mitt Romney's opposition to the law as evidence that Republicans are interested simply in protecting elite bankers. And Republicans have made this all too easy — expressing stern opposition to the law as a whole, and even urging its repeal, without ever explaining to the public what in particular they find troubling about it. In their efforts to significantly undercut Dodd-Frank (by pressuring regulators to weaken new rules and issue them more slowly), and in their reflexive hostility to financial regulation more broadly, Republicans have fallen into the Democrats' trap. They have been left to defend financial institutions in one scandal after another — most recently when an errant trade by J. P. Morgan cost the "too big to fail" firm nearly $6 billion and in the midst of last summer's LIBOR price-fixing debacle — while Democrats claim to stand up for the average person. To make matters worse, conservatives are actually betraying their own principles in this careless defense of Wall Street: In serving as champions of finance, they diminish their standing as champions of the free-enterprise system more broadly.

A better approach is possible. Republicans can and should defend free markets and free enterprise, but they should also make clear that free markets require a financial sector that serves businesses, investors, and taxpayers instead of exploiting them. Just as Republicans have championed limits on the ability of plaintiffs' lawyers to profit at the expense of productive businesses, they should lead the push to limit the ability of the financial sector to make risky bets with taxpayers' money.

The key is to insist on the correct regulations — regulations informed by an accurate understanding of what caused the financial crisis, of what people object to in our current financial system, and of what types of reforms can best address those concerns. After all, Americans don't oppose wealth generation; by and large, they are risk-tolerating, entrepreneurial people. What they object to is bankers' using our financial system for reckless gambling, and the taxpayer bailouts that result from it.

An approach to financial regulation that addressed these concerns would not only help our economy: It would also go a long way toward rehabilitating public perceptions of our free-market system. In the aftermath of the November election, developing principles for financial reform that are pro-market without being blindly pro-finance can serve as the starting point for a new Republican agenda. It is therefore worth exploring precisely what ails our current approach to finance and developing a coherent regulatory approach capable of curing it.

FINANCE VERSUS MARKETS

The logical place to begin is by correcting a mistaken premise that has informed conservatives' resistance to financial regulation. Much of their opposition stems from the view that efforts to constrain the activities of financial firms represent inappropriate government interference in our market economy. And as conservatives are defenders of the market, they must necessarily be defenders of the financial-services industry, or must at least be opponents of financial regulation.

In adopting this pose, conservatives make errors of both tactics and principle. There is powerful evidence to suggest that the modern financial industry largely serves its own interests at the expense of the rest of the economy, rather than creating wealth more broadly. Opponents of financial regulation designed to address such rent-seeking behavior are therefore easily perceived as defenders of misbegotten privilege rather than of free-market competition. A sounder approach would be to focus on championing free markets in real goods and services, defending the role of financial intermediaries when they serve those markets and supporting regulation when they instead prey on the rest of the economy.

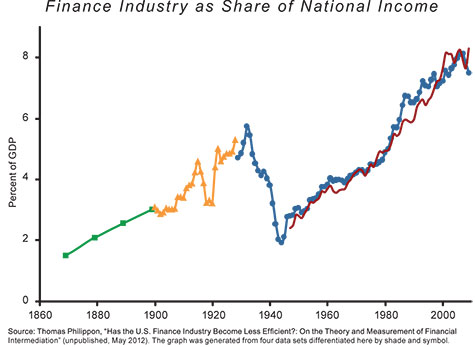

The tensions between a thriving democratic capitalism and today's brand of finance have unfortunately been lost on many conservatives. Their reflexive defenses of all private enterprise have blinded them to the real harms that the financial sector — often propped up by government supports — has inflicted of late on other sectors of the economy. But recent economic analyses, such as one by economist Thomas Philippon, have shown that the growing size and inefficiency of the financial sector have become a tax on real business activity. As the figure below illustrates, in 1980, the financial sector's share of gross domestic product passed its share of GDP at the height of the financial boom of the 1920s; it has continued to increase ever since, reaching its peak (of more than 8% of GDP) in the 2000s.

One could argue that some of this growth results from firms' increasing use of financial instruments, or the fact that the typical American requires more financial services. But Philippon adjusts for these factors and finds that, even when they are taken into account, the financial sector has bloated because its overall efficiency has declined by nearly 50% since the 1970s — despite the information-technology revolution, and despite the supposed benefits of financial deregulation.

Our financial markets, then, have simply gotten more expensive. But are they at least providing increased value, better services, and other benefits to justify the cost? Again, Philippon suggests not. With co-authors Jennie Bai and Alexi Savov, he shows that, even with deregulation and the advance of information technology, markets are no better at predicting the future prices of assets than they were in the past. The added expense has not improved the quality of the information markets are credited with supplying.

Moreover, Mark Aguiar and Mark Bils show that, over the period from 1980 to 2007, the fraction of fundamental risk borne by individuals has stayed constant or increased, indicating that the extra expense of our financial markets has not provided valuable insurance. In other words, despite the massive innovation that, according to the financial sector's champions, was supposed to reduce and spread the risks individual investors face, Aguiar and Bils show that today's financial markets may actually increase those risks. Indeed, as Aguiar and Bils do not address the fallout from the financial crisis, their paper probably understates the problem; the allocation of risk has probably worsened since the late 1970s. It is therefore likely that the additional cost of the financial sector is in fact paying for wasteful gambling and bailout arbitrage — where banks take risks financed by taxpayers, as discussed below — rather than valuable economic activity.

In addition to increasing the cost of capital to firms, the growth of the financial sector is draining the pool of labor that businesses rely on. Although the figures have dropped somewhat since 2008, huge numbers of graduates from top universities and business schools are still making their careers in the bloated financial sector rather than taking jobs as engineers, executives, and entrepreneurs. For example, of the Princeton seniors who had full-time jobs at graduation in 2007, 43% went into finance. Republicans often (rightly) attack proposals to limit CEO compensation on the argument that such restrictions will deprive firms of valuable talent. But they should also recognize the degree to which the financial sector — which lures people with the opportunity to reap fabulous wealth by gambling on the taxpayer's dime — similarly deprives the real economy of talent.

The bloating of finance has also undermined Americans' faith in free enterprise and the low taxes that foster economic growth. Americans are naturally hostile to class-war arguments for wealth redistribution, but they are just as wary of wealth they believe is unearned or misbegotten. The public case for free markets relies on the commonsense conviction that people who work hard and contribute to society deserve compensation commensurate with their efforts. Those who champion higher taxes realize that, to the extent they can convince Americans that the wealthy do not in fact deserve their riches, they will find a much more receptive audience for their cause.

The financial crisis has thus played into the hands of liberals by revealing that the super-rich in America today are less like Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and more like disgraced Lehman Brothers chief Dick Fuld. Economic data confirm this impression. Economists Steven N. Kaplan and Joshua Rauh recently looked at the top 0.01%, 0.001%, and 0.0001% of the income distribution to determine what fractions of those groups were made up of "Main Street" executives from companies in the real economy and what fractions consisted of investment bankers, hedge-fund managers, and other financial-sector executives. They found that, in 2004, the shares of these income groups composed of financiers were two to three times as large as the portions consisting of other business executives. In fact, the top five hedge-fund managers likely made more than the top 500 non-financial executives. The financial sector's representation in these top tiers of wealth has increased roughly tenfold since the 1970s.

The wealthiest Americans are thus increasingly people whom their fellow citizens would view as "unproductive," rather than the captains of industry conservatives have typically lauded (and sought to protect from confiscatory taxes) for their innovation, hard work, and entrepreneurial spirit. It becomes harder to resist calls for high progressive taxes when those taxes increasingly target the incomes of gamblers who bet recklessly, trusting that taxpayer-funded bailouts would make them whole if disaster struck. Conservatives who believe in defending the American tradition of free enterprise against crushing tax burdens should therefore fight to keep the activities of Wall Street financiers from corrupting Americans' perceptions of business and honest wealth. For that matter, conservatives who believe that wealth should flow to the productive entrepreneurs and executives who create it should be just as worried about the tax the financial sector's inefficiency imposes on that wealth as they are about the taxes imposed by government.

In all these ways, the confusion of a pro-finance position for a pro-market one — as well as the failure to see how the growth of finance has in fact undermined business and enterprise — has been a major obstacle to more sensible financial regulation. Learning how to distinguish between the narrow interests of the financial sector and the broad cause of economic growth is an essential first step toward improved policy. Only then can lawmakers focus on regulations tailored to the specific problems in our financial sector — the problems that cause most Americans concern.

But what exactly is wrong with our financial markets? Why are they less efficient than other markets? Though these are complicated questions with many possible answers, two general explanations present themselves. First, financial markets are prone to gambling, which is not socially valuable behavior. And second, they are subject to panics and collapses, which can cause harm throughout the economy. These are the tendencies in our markets to which so many Americans object. They are therefore the problems that our financial regulations should seek to address.

CASINO FINANCE

In their enthusiasm for free markets, some conservatives — especially those of a libertarian bent — have lost sight of a unique feature of financial markets that has always troubled social conservatives: They can be used to gamble.

This is not to disparage traditional stock and bond markets, which emerge from basic investments of capital in firms producing products of value that contribute to economic growth. The reason for concern, rather, is the rise of derivatives. Derivative securities are unusual financial instruments; they are built upon other economic transactions, and reflect an effort to predict what the outcomes of those other transactions will be. An investor might purchase a credit default swap, for instance, predicting that a euro-zone country will be unable to repay holders of its sovereign debt.

Often, derivatives serve as useful safeguards: A bet on the futures market, for example, allows an oil producer to protect himself from the risk that crude prices will fall and an oil consumer to protect himself from the risk that prices will rise. But because derivatives are built upon underlying assets and transactions, they are not naturally limited in the same way as traditional securities: There is only so much stock in a company to trade. There are many fewer such curbs to stop derivatives from being abused for pure gambling — from using a bet on the price of oil for the same purposes as a bet on a horse race or a spin of the roulette wheel.

The fact that a particular derivative can be used for both legitimate insurance purposes and reckless gambling makes derivatives in general tricky to regulate. An early derivative — the life-insurance contract — offers an illustrative example. Life insurance was initially developed to help people spread risk: A wage earner would buy insurance on his own life to protect his dependents from a loss of income in the event of his death. But when life insurance was introduced, many people used the policies to gamble on the lives of famous people — and in a way that added risk instead of mitigating it. When two people place bets on whether a prime minister will die in the next year, each has exposed himself to new risk that did not exist before. In some countries, governments responded to this gambling by outlawing life-insurance policies altogether. In the 18th century, the British government chose a more sensible route, outlawing the use of policies for gambling but preserving their essential function as insurance.

In particular, a rule known as the "insurable interest doctrine" — which first entered British law by an act of Parliament in 1746, and then became a part of the common law inherited by the American legal system — required that individuals seeking to buy insurance have a stake in the event against which they sought to be insured. A person could not, for instance, purchase a life-insurance policy to bet on the death of the prime minister, but he could purchase life insurance to protect his dependents or buy health insurance to protect himself. The aim was to prevent people from disguising gambling as legitimate insurance transactions: The rule allows a person to enter the insurance market to protect himself against financial loss, not to enable him to reap a windfall from a random event. If this rule had been applied to credit default swaps — which are mostly used to gamble on the failure of a debtor rather than to insure against it — the enormous multi-trillion-dollar CDS market would never have formed, and the financial crisis would not have been as severe.

In today's derivatives market, however, no such sensible restriction exists to separate the use of the instruments as insurance from their use as gambling devices. A holder of Italian bonds can of course protect himself from the country's defaulting on its debt by purchasing a CDS on those bonds. But two people who don't hold any of Italy's debt can also purchase the swaps, using them to gamble on an Italian default. In the first case, as with the life-insurance policy, aggregate risk is reduced; in the second, it is increased.

This duality of purpose is not a matter of concern for all derivatives. Indexed mutual funds and commodities-futures markets are largely devices for spreading the risk of equity investment or commodity prices among the public, but are inconvenient for gambling. Economists have recently developed derivatives that allow home owners to protect themselves from declines in the values of their homes, so that they will be able to sell without incurring losses and move if they need to change jobs; this, too, functions almost exclusively as insurance.

But some derivatives — for example, those with values that are functions of the volatilities of particular securities — are almost certainly used only for gambling. These derivatives, such as correlation swaps and the tranched collateralized debt obligations (or CDO) products that figured so prominently in the financial crisis, cannot really function as insurance, since individuals generally do not need to protect themselves against volatility and correlation (as opposed to loss). And the explosive growth in the derivatives market in the 1990s and 2000s produced a larger and more diverse set of market-based gambling opportunities than ever before. Bets are now possible on all sorts of obscure properties of stocks and bonds, such as the correlations of the volatility of different stocks.

What exactly is wrong with such gambling on financial products? A libertarian might say "nothing at all": Any voluntary transaction that does not directly harm third parties should be permitted. But there are several problems with this view. While gamblers do voluntarily take on risk, they may not fully or rationally understand what that risk entails. Many people gamble because they have false beliefs about their probability of winning, or because they are addicted — they simply cannot help themselves, even as they make themselves poorer.

Most states therefore ban most forms of gambling. And when gambling is allowed, it is permitted only in restricted settings, subject to regulation. For example, states may limit the sizes of wagers and losses, or prohibit casinos from extending credit to customers, or place caps on how many casinos will be permitted to operate and restrict where they can operate. Casinos are places where entertainment is also provided, so that people's losses are to some extent offset by the pleasantness of the experience; moreover, it is fully clear that the purpose of the establishment is gambling.

By contrast, when people gamble in the financial markets, they often do not comprehend the nature of the risks they are assuming; they are not quite aware that they are even gambling. They simply assume, rather, that their beliefs about some security are more accurate than the beliefs held by people on the other side of the transaction. This phenomenon is internally contradictory: The seller and the buyer of a derivative security in a transaction with no insurance value cannot both be correct about the value of the security. Otherwise, the transaction would not take place. Someone is mistaken, which means that the transaction does not contribute to social wealth: One party loses exactly what the other party gains, and both are made worse off by the additional risk they take on in this bargain. Compare this situation to an ordinary transaction in the real economy — say, when a buyer hands over a dollar to a seller in exchange for a tomato. Each party prefers what he receives, producing a net social gain.

Even in financial markets, the risk assumed in more standard transactions — like the purchase of traditional stock — is understood and accepted as part of the costs of production. When a person buys a share of Procter & Gamble, he is taking some risk that the price will fall, but he is also providing the company with capital — capital that the firm can then use to research and develop new products, expand its facilities, or hire new workers. In these cases, net contributions are made to the economy. Financial-market gambling, on the other hand, deliberately generates risk to allow people to get ahead without making the productive economic contributions usually required as a condition of acquiring wealth.

Reasonable people disagree about the extent to which casino gambling should be permitted, but no one doubts its essential purpose — entertainment — or that it produces specific harmful effects, like addiction and the neglect of family and community obligations. The purpose and dangers of gambling through the financial markets are not always as obvious. But the effects are inevitably worse, because, by inflating financial markets without producing social gain, financial gambling sets the stage for systemic crises like the one we experienced in 2008.

In fact, the crisis is much less surprising when one realizes that such gambling has become far easier in the past 20 years as Congress and government regulators have relaxed restrictions like the insurable-interest doctrine. The spread of gambling in the financial system was a consequence of legislation that received bipartisan support but was pushed by the Clinton administration: The Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 exempted certain financial transactions from regulation under state gambling and insurance laws that were designed to prevent the abuse of financial products for gambling. One of the law's major effects was thus to prevent states from regulating gambling transactions in financial markets as they saw fit.

This might explain why 50 House Republicans opposed or tried to limit the reach of the CFMA. But it is instructive to compare this limited response with Republicans' overwhelming support for the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006, which prohibited internet gambling web sites from evading state laws. As Pennsylvania senator Rick Santorum put it with regard to the latter bill, "It's one thing to come to Las Vegas and do gaming and participate in the shows and that kind of thing as entertainment, it's another thing to sit in your home and have access to that. I think it would be dangerous to our country to have that type of access to gaming on the internet." Santorum's logic applies as much to gambling in the financial markets as to gambling over the internet; indeed, gambling in the financial markets is gambling over the internet.

This reality presents conservatives with an opportunity to play on their perceived strengths. Rather than allowing liberals to paint the financial crisis as an outgrowth of excessive capitalist greed, conservatives should demonstrate how it resulted from the failure to keep gambling from infecting otherwise healthy financial markets. Identifying the crisis with the spread of gambling — blaming people who put the whole economy at risk to obtain riches they did not earn — would allow conservatives to speak to what really enrages Americans about the financial crisis and Wall Street culture.

And in framing their regulatory approach as an effort to remove gambling from the financial sector, conservatives would be able to argue about this subject with greater credibility. For many years, leading Republican legislators have taken strong stands against the expansion of gambling to placate Indian interests or to raise revenue for state governments. Like Santorum, many have also opposed the spread of gambling to the internet. Democratic congressman Barney Frank, on the other hand, was one of the leading opponents of restrictions on internet gambling.

Republicans' long track record of seeking to limit other forms of gambling may well persuade Americans that they are serious about addressing gambling on Wall Street. This could help mitigate public skepticism about conservatives' sincerity when it comes to financial reform. And that, in turn, could undo some of the damage caused by Republicans' confusion of what is good for the financial industry with what is good for a free-market economy.

AVOIDING BAILOUTS

Of course, one of the greatest dangers of gambling in the financial markets is that, unlike with casino games, the people placing risky bets are doing so on the taxpayer's dime. Many financial-market gamblers know that they will keep any gains if their bets prove right; if they lose their bets in spectacular fashion, however, their losses will be covered by government bailouts. This kind of "bailout arbitrage" is both very costly and very dangerous.

The problem arises from the central role banks play in the functioning of the economy. Because most individuals are happy to keep most of their money in the bank at any time, banks operate on the principle of fractional reserves, meaning that the institutions do not keep enough cash on hand to pay off all depositors if they all ask for their money at the same time. This allows banks to underwrite economic growth, but also exposes them to runs in which many or all depositors seek to withdraw their money at the same time because of fears about the banks' solvency.

Economists consider such runs to be devastatingly costly, as they destroy the ability to sustain the borrowing allowed by the fractional-reserve system along with the lending knowledge accumulated in banks over many years. But since the work of Walter Bagehot in the 19th century, economists and governments have understood how to address this problem: When banks fail, the government must act as lender of last resort.

Today, the government serves this role in two ways. First, it compels banks to buy government-supplied deposit insurance, which covers depositors up to $250,000. Second, it provides emergency loans at below-market rates — bailouts — to any financial institution whose collapse would take down enough banks with it to endanger the entire economy.

Few seriously doubt that governments must play this role. This is not a partisan view: Deposit insurance has had bipartisan support for decades and exists in all advanced economies. Almost half the Republicans in the House and more than half the Republicans in the Senate supported the TARP bill, which of course was proposed by a Republican administration. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve, under the leadership of Republican appointees, independently lent trillions of dollars to ailing firms.

But while this lender-of-last-resort function may be necessary, it nevertheless causes moral hazard — a perverse incentive for financial institutions to make risky loans. These high-risk loans are very profitable if they pay off; if they do not, the government absorbs the loss, meaning there is relatively little danger to the banks. The government must therefore regulate banks to ensure that they do not take excessive risks with the taxpayers' money — much as auto insurers impose penalties for speeding tickets to discourage policyholders from taking risks with the companies' money.

The methods for preventing banks from taking excessive risks that could lead to bailouts are well established and not terribly controversial, at least in principle. Regulators use capital-adequacy regulations to ensure a protective equity cushion: If the bank gambles excessively, the shareholders of that equity are the people who lose; since the bank's executives are accountable to shareholders, these requirements offer healthy incentives not to gamble recklessly. Regulators also restrict the types of loans and other financial transactions that banks engage in — for example, by preventing them from putting too much money at stake in one borrower, who may fail, or one sector of the economy, which may suffer a downturn. This is only prudent: While a bank will generally not fail as the result of a single default — most institutions can easily bear the downside of one loan that is just part of a large portfolio — massive, multi-party bets that depend on a single variable, like the state of the housing market, can wipe out several institutions and leave taxpayers on the hook.

In imposing these requirements, the government acknowledges a basic tradeoff. If it allows banks to take more aggressive risks, the economy can grow faster, but at the expense of taxpayers who will face the increased probability of a bailout. If the government restricts the risks banks take, it reduces the likely bill faced by taxpayers, but may also slow down economic growth. This means that when conservatives argue for less financial regulation, they are implicitly claiming that the risk of moral hazard is small relative to the potential gains from economic growth. The financial crisis of 2008 should certainly give pause to those who hold this view; the fact is that, under both economic theory and political reality, government action is necessary to limit moral hazard and bailout arbitrage.

And conservatives should remember that government action, once required in the midst of a crisis, may not end with bailing out banks. After Republicans acquiesced to the necessity of TARP, the government used its new powers to involve itself in industrial policy on a scale not seen in 80 years. It picked winners and losers not only in the financial sector but also in the real economy, where it decided to bail out car companies and to make credit available to ordinary firms. It fired private-sector managers and appointed new CEOs. It regulated compensation of executives. It provided more generous rescue packages to some institutions than to others on the basis of obscure — and possibly politically tainted — criteria. And it then used the turmoil unleashed by the crisis to expand government involvement in the health-care and energy sectors. Such overreach was not unique to the 2008 crisis: Recall that while the Great Depression started as a financial crisis, the government did not respond simply by imposing regulations on the financial industry. Instead, it permanently expanded its role in nearly all sectors of the economy.

In addition to reducing gambling, then, conservatives should focus their regulatory approach on making the bailout phase as unlikely as possible. By embracing regulations that prevent bailouts — and the highly interventionist policies that often follow — policymakers can in fact help preserve conservative principles of limited government while also addressing the outcome of the financial crisis that deeply angered Americans who were left to pay for the consequences.

PRINCIPLES FOR REFORM

Given that there are good reasons for conservatives to support financial regulations on pro-market, limited-government grounds, should they simply put aside their objections to Dodd-Frank? They should not, because some of the problems with Dodd-Frank are simply too great to abide. But especially in the wake of the recent election, which of course makes any near-term repeal of Dodd-Frank impossible, conservatives should seek ways to address the law's problems and make it as useful and effective as it can be.

Like a lot of well-intentioned reform legislation with limited grounding in economic theory, Dodd-Frank is tremendously vague and flexible. It is therefore liable in its current form to enable problematic interventions in the real economy at the discretion of politically motivated administrators. For example, in various provisions designed to address "speculation," the law grants power to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission to identify derivatives that should be subject to state gambling laws. Dodd-Frank defines a derivative that is subject to state gambling regulations to be any financial instrument with "a pari-mutuel payout or [one that is] otherwise...determined by the Commission, acting by rule, regulation, or order, to be appropriately subject to such laws."

"Pari-mutuel payouts" are arrangements in which the payoff from a pool of participants is given to the winner of some bet, once commissions are removed. But given that all derivative securities in some sense have this structure (their prices are determined by a market equilibrium and payoffs are given to the winner of a "bet" on some outcome), the CFTC and SEC have essentially arbitrary authority to define any, or no, derivative to be subject to state gambling laws. Dodd-Frank articulates no principles on the basis of which such determinations should be made.

For example, in April, the CFTC banned as gambling products derivatives that enabled people to bet on the outcome of this fall's presidential election. Given the dangers posed by gambling in the markets, this decision was sound — but the CFTC provided no economic analysis to explain why it believed that bets on the presidential election would have less economic value than bets on, say, the volatility of equity indices, which the commission does allow. It seems likely that the CFTC's real motivation in banning election bets had less to do with the economic merits of the contracts than with their exoticism and political sensitivity. This suggests that similarly political interpretations of Dodd-Frank's sweeping rules could be used to, for instance, limit politically sensitive short sales of the bonds of troubled European sovereign debt or purchases of oil futures near an election. This is a worrying possibility, because political distortions of real markets through finance — in the case of housing, through government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — helped bring about the financial crisis in the first place. Similar interventions could exacerbate crises in currency, energy, or sovereign-debt markets.

Similar problems in fact plagued the early years of enforcement of the Sherman and Clayton Anti-trust Acts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While monopoly and collusion create obvious economic harms, the failure of these pieces of legislation to clearly identify the nature of those harms, as well as to stipulate how those harms would be measured, allowed the laws to be exploited for political gain. Enforcement agencies were able to target politically unpopular firms by rallying populist public sentiment.

This began to change in the 1970s and '80s, as lawyers and economists discovered that objective economic principles could be applied to determine whether corporate conduct harmed competition (and therefore consumers). In devising regulation based on these principles, there was a risk: Overly narrow, detailed rules could easily be circumvented by firms with the resources to hire teams of expert lawyers, who would then help the firms obey the letter of those laws while violating their spirit. So to ensure that the spirit of the laws was also respected, regulatory agencies, through their guidelines, clearly articulated the underlying principles on which the evaluation of firms' activities should be based. This approach was effective both in largely keeping politics out of enforcement and in fostering a culture of dispassionate economic analysis.

The Dodd-Frank legislation, on the other hand, is full of specific — and thus easily avoidable — rules, and yet is astonishingly vague about the economic principles it seeks to uphold and the goals it seeks to achieve. Without reform, the law thus seems guaranteed to ensure both evasion of its key provisions by financial firms and exploitation by opportunistic political appointees.

Luckily, two great accomplishments of the conservative legal movement provide models for how to avoid these problems. First, in the case of the Sherman and Clayton Anti-trust Acts, despite the vagueness of the original legislation, conservative scholars and then judges and policymakers developed clear economic principles to guide the laws' implementation. Agencies then hired talented economists to apply these principles rationally. Today, this approach to anti-trust law has achieved bipartisan consensus, fully replacing the old mix of populism and confusion.

Second, conservatives can learn from the model of cost-benefit analysis in regulation. In 1981, in an effort to limit over-regulation, President Ronald Reagan ordered all regulatory agencies to conduct cost-benefit analyses of proposed rules. His order, while originally attacked by some Democrats, has been renewed with small modifications by every subsequent president, regardless of party.

By shaping the enforcement of existing laws around sound economics, cost-benefit tests provided a clear basis for regulation. The Environmental Protection Agency, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and other regulators now provide more sophisticated and comprehensive explanations of their regulations, usually grounded in rigorously analyzed statistical data, than they ever have in the past. This helps both to increase the quality of their regulations and to limit their manipulation for political purposes.

Reagan's executive order had little impact on the financial agencies, which are more independent under the law than the EPA is. But the principles we articulate above (and in more detail in recent academic work) provide a firm basis for extending regular cost-benefit analysis to financial regulation. And efforts to implement such analysis are already underway; indeed, in recent years, the courts have increasingly pressured financial regulators to weigh costs against benefits in the course of their rule-making. In July 2011, the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit struck down an SEC regulation that required corporations to give shareholders more control over elections of directors because the rule did not satisfy a cost-benefit analysis. The court pointed out that the SEC had ignored empirical studies casting doubt on the agency's claim that the rule would improve the performance of corporate boards and increase shareholder value.

On the congressional front, Republican senator Richard Shelby of Alabama has recently proposed legislation requiring government agencies that regulate the financial industry — including the Federal Reserve, SEC, and CFTC — to conduct rigorous cost-benefit analyses of their proposed regulations. If a regulation failed the cost-benefit test, the agency would be prohibited from issuing it; if the agency went ahead and issued the rule anyway, a court would have the authority to vacate the regulation.

The approach represented by these policy models offers the right foundation for reforming Dodd-Frank and ensuring its economically sound implementation. More specifically, this reform and implementation should be guided by four aims.

The first is clarity. The underlying goals of any proposed rules should be clearly stated; the economic principles informing them should be clearly articulated; and the methods of quantitative evaluation that will be used to determine whether those goals are met should be clearly established and explained. This clarity will help guide cost-benefit analysis; at the same time, it will help ensure that regulations are not so specific as to be easily circumvented and will help constrain political abuse.

What would such clarity look like? Today, the EPA, OSHA, and NHTSA attach standardized dollar values to a proposed rule's probability of saving a human life. It would be perfectly reasonable for the government to establish similar standardized dollar values for reducing the probability of a financial crisis by a fixed amount. This "statistical value of a crisis" would bring greater discipline and accuracy to claims of financial regulations' benefits and to claims about the harms caused by private market activities.

These standardized measures would also help in addressing the problems of gambling and bailouts. They would attach uniform assessments of value to the benefits provided by derivatives (as insurance, and as the foundation for markets that provide useful information to businesses and investors) as well as to the harms derivatives cause (through gambling and bailout arbitrage). The existence of these comparable measures would help regulators sort between productive and unproductive economic activity, building on principles developed in recent years by economists Markus Brunnermeier, Alp Simsek, and Wei Xiong, among others.

Second, cost-benefit analysis based on these principles should be applied to all significant rules issued under Dodd-Frank. While financial regulators do now perform something they call cost-benefit analysis, it does not match the rigor of the analysis conducted by other rule-making agencies. Despite the abundance of information about financial markets, the regulators responsible for this sector rarely use empirical data in reviewing proposed rules. The government should thus make every effort to ensure that these data are used as the foundation for rigorous evaluation of any proposed regulations.

Third, such cost-benefit analysis should apply not only to new regulations but also to exemptions from state gambling laws granted to derivatives under the CFMA (and its extension through Dodd-Frank). This requirement would reduce the risk that this regulatory discretion would be used for political purposes unrelated to financial principles, while also mitigating the danger of blanket exemptions allowing rampant gambling through financial markets.

In some recent academic work, we detail how such a system might operate. With the proposal of a new financial derivative for trading, a rigorous cost-benefit analysis would be conducted to determine whether it would serve primarily to facilitate beneficial insurance or harmful gambling. A projection would be made based on available data about the risks faced by market participants, the potential for gambling created by a security (which could be judged using surveys or experiments with markets), and the interaction of the new security with existing capital and tax regulations. Only products judged to primarily serve useful insurance or price-discovery purposes would receive CFMA exemptions under federal law.

This process would imitate the quantitative empirical analysis conducted by the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice Anti-trust Division in evaluating the anti-trust merits of a merger. And it would restore an appropriate balance, preventing the use of federal law to legalize interstate gambling while also ensuring the smooth functioning of markets for economically valuable products.

Finally, regulatory discretion regarding which principles and priorities should guide rule-making and cost-benefit analysis should be strictly limited by law. A rule that could reduce housing foreclosures, for example, may have its benefits, but these should not be judged by regulators tasked with ensuring the health of financial markets. The job of financial regulators is not to make housing policy; they must be forced to focus narrowly on the financial system they are charged with protecting.

Embracing a plan like Senator Shelby's, given substance by the principles outlined above, would allow conservatives to take the lead both in limiting the abuses of our financial sector and in controlling the institutions created to stem those abuses. Indeed, embracing this regulatory approach would be conservative in the traditional meaning of the term: It would return us to the earlier period of financial stability and sensible regulation that lasted from 1933 to the 1990s, albeit updated to reflect the innovation that has occurred in our financial markets since.

AN OPPORTUNITY

There is no denying that Dodd-Frank contains much to irk conservatives and others who wish to see fewer government intrusions into our market economy. Nevertheless, some sort of strengthened oversight of our financial sector was required after the '08 crisis, and to the degree conservatives simply oppose Dodd-Frank, or new regulation in general, they risk alienating a legitimately concerned American public. They also risk ceding what should be natural conservative intellectual and policy territory to the left.

After all, regulations along the lines proposed above would help conservatives defend markets and entrepreneurs against the implicit tax imposed by the depredations of politically connected financial institutions. They would also help avoid the higher actual taxes likely to result from voter fury over those depredations. They would align with longstanding conservative opposition to gambling, and help avoid the taxpayer bailouts that fuse government with a crucial sector of the economy and often facilitate wider government interference. They would reflect conservatives' support for federalism, and embrace Reagan's acknowledgment that regulations should be evaluated and adopted based on their service to the broader economy.

In some ways, Dodd-Frank in fact presents conservatives with a useful mechanism for advancing this vision. Given the political balance in Washington, the law is not likely to be repealed any time soon, but many of its provisions still have yet to be defined. Despite its immense length, the law itself was astonishingly light on details to be applied in its implementation. Much, if not most, of the regulation that it will create has been left up to regulators to determine.

This ambiguity is both dangerous and promising. The danger is that the law could be abused to impede crucial functions of the market, but the promise is that the law could be implemented on the basis of smart economic principles. If conservative policymakers know what they want out of financial regulation, they will know how to apply the considerable leverage they still have to regulators' work in the coming years — knowing what to endorse and defend, what to staunchly oppose through legislative and legal efforts, and where to press for change. If they do, they will be able to seek a public mandate as the party of economically sound, impartial financial regulation, rather than as the party of casino finance.